Tuzla Fortress. Putin's provocations and Kuchma's unexpected discovery that Ukraine is not Russia

"I’m busy, pal. Getting a battalion ready for the Tuzla landing."

"I’m in charge of the island, Kolya. There will be blood, a lot of it. Think before you act."

This conversation took place in early October 2003 between two men who had both graduated from the Frunze Military Academy in Moscow a year before the Soviet Union collapsed. Both were paratroopers; they had served together in Azerbaijan.

One of them was Mykhailo Koval, then a Lieutenant General and the First Deputy Head of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine.

The other was Nikolai (Kolya) Ignatov, then a Major General and the Commander of the 7th Air Assault Division of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

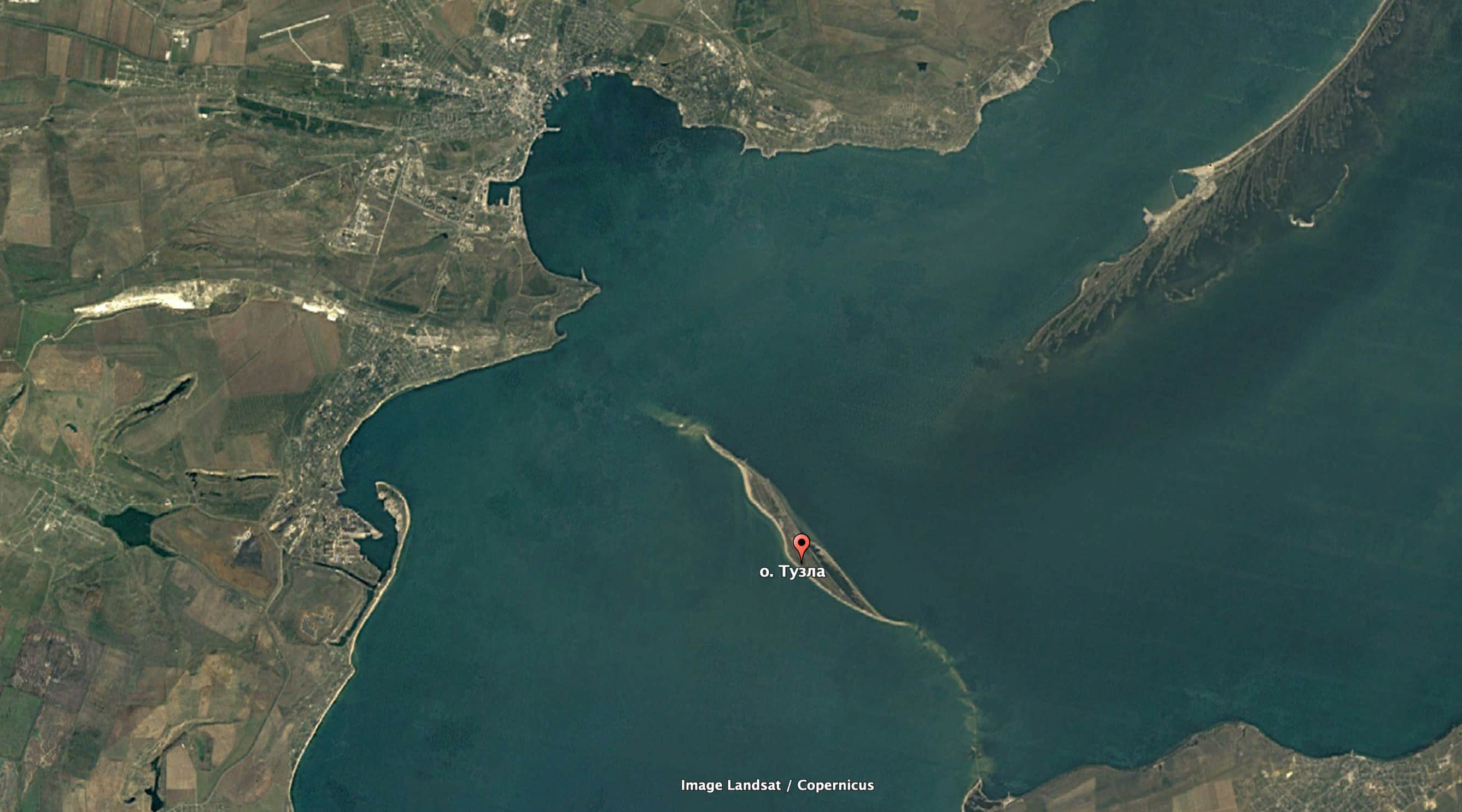

Koval had called Ignatov to figure out what was happening on the Russian side of the Russian-Ukrainian border. They were talking about Tuzla – a Ukrainian island in the Kerch Strait which separates Crimea’s Kerch Peninsula in the west from Russia’s Taman Peninsula in the east.

Russia had gathered heavy-duty trucks, excavators and bulldozers in Taman in late September 2003 and started to build up a dam in the shallows of the Kerch Strait, edging closer towards Tuzla Island. The Kremlin refused to comment on what was going on, giving the impression that the construction was the initiative of businessmen from Russia’s Krasnodar Krai.

It looked as though Russia was positioning itself to capture Ukrainian territory. There was not a single Ukrainian border guard in sight on Tuzla at the time.

The Tuzla epic has many layers – political, economic, and military – but first and foremost it is the story of some Ukrainian border guards who found themselves in the right place at the right time, and who acted in accordance with the motto of "do the right thing, come what may".

Ukrainska Pravda spoke to the key figures in the events that unfolded around Tuzla in 2003: Colonel General Mykhailo Koval and Serhii Kunitsyn, then head of the government in Crimea. Former president Leonid Kuchma answered our questions in writing.

What provocations did Putin carry out, how did he try to hide, and how did he grope about for red lines?

How did looking through his binoculars on Tuzla Island help President Kuchma realise that Ukraine was not Russia?

How did General Koval and his 300 Spartans create the Tuzla Fortress with the help of dummy tanks, three helicopters, and chicken legs?

And why did the events of 2003 almost culminate in a war?

All these questions and more will be answered in this story as it reconstructs the events of the hot autumn of 2003.

A Russian crooner’s concert, Putin’s love for Crimea, and Kuchma among cornflowers

Eight months before the onset of the Tuzla crisis, on 27 January 2003, Presidents Leonid Kuchma and Vladimir Putin had inaugurated a "Year of Russia in Ukraine" at the Ukraine Palace in Kyiv.

A popular joke at the time quipped that it was Russia’s 349th year in Ukraine since the Treaty of Pereyaslav [an agreement signed on 18 January 1654 by Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, leader of the Cossack army in Ukraine, and emissaries of the Russian tsar Alexis, under which Ukraine submitted to Russian rule as an autonomous duchy under Russian protection. Khmelnytskyi had sought Russia’s protection for a revolt he had been leading against Polish rule in Ukraine since 1648 - ed.].

Guests at the festive concert at the Ukraine Palace were entertained by popular Russian crooners Iosif Kobzon and Larisa Dolina, as well as Lyube, reportedly Putin’s favourite band, and Berizka (Birch Tree), a dance group.

The two presidents addressed the crowd before the concert. Putin assured everyone that the good relations between the two countries would "continue to grow and multiply through the years". Kuchma promised that the "nobility of thoughts and the greatness of aspirations of the two great nations" would be on full display.

The nobility of thoughts was indeed on full display at the feast that followed the concert, where lavish quantities of vodka and caviar were served.

The mood set by the high-profile inauguration of the "Year of Russia in Ukraine" would be sustained in the months to come.

Putin visited Ukraine four times in 2003, and during three of those visits his meetings with Kuchma were held in Crimea.

"I saw Putin on many of his visits to Crimea," says Serhii Kunitsyn, who headed the Crimean government in 2003. "I saw him ‘fall in love’ with Crimea. Russian politicians and oligarchs also felt this happen; they started to want to invest their money [in Crimea]. The more they invested in the peninsula, the more I realised that this was about more than just cooperation and business interests."

As it happens, 2003 was also the year when anyone who disagreed with Putin’s agenda was purged from Russian TV; everything was set up for it to operate as a propaganda machine. It was during the Tuzla debacle that anti-Ukraine hysteria became a commonplace feature of the Russian information space.

There is another important bit of international context which helps explain the events in Tuzla.

The West had distanced itself from Kuchma following the murder of Ukrainska Pravda’s founder Georgiy Gongadze in September 2000 and the release of the Melnychenko tapes, which implicated Kuchma in the case.

The so-called Kolchuga scandal – when Ukraine allegedly sold four Kolchuga radars to Iraq, circumventing international sanctions – further complicated Ukraine’s relations with the West.

Kuchma’s decision to send Ukrainian troops to Iraq as part of the international peacekeeping mission somewhat eased the tensions, but still, Putin chose to stage provocations on Tuzla at a time when Ukraine could not count on help from the West. Putin’s calculations were correct: in the midst of the conflict over Tuzla, then-NATO Secretary General George Robertson declared that the Alliance would not intervene and the issue had to be sorted out by Ukraine and Russia.

On 3 September 2003, Kuchma presented his book, Ukraine Is Not Russia, at an in-person event in Moscow. The cover shows Kuchma wearing a white shirt and tie and squatting in a meadow, smiling at some Ukrainian cornflowers.

Kuchma met with Putin on Byriuchyi Island, a Ukrainian spit in the northwestern part of the Sea of Azov, on 18 September 2003, ahead of the Commonwealth of Independent States meeting in Yalta, Crimea, at which the presidents of Ukraine, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan signed an agreement creating a Common Economic Space (CES). [The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional intergovernmental organisation that was formed following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991; its current members are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova (suspended participation), Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan – ed.]

"Of course, Putin didn’t once mention the dam during that meeting. He wouldn’t have. If you’re planning a special operation against someone, you’re not likely to discuss it with them," Kuchma says.

"That conversation ended quite diplomatically. He said he was going on an extended trip to Southeast Asia. I told him I was going to visit several Latin American countries. We wished each other luck.

Soon it became clear why he was so interested in my long absence [from Ukraine]."

Tuzla’s 300 Spartans

"General, you’ve lost your mind!" were the first words Mykhailo Koval heard when he finally reached the Presidential Administration on the phone on the morning of 29 September. Koval wanted to tell Kuchma about the dam that was being erected between Russia and Tuzla, but Kuchma didn’t pick up, and he ended up talking to Viktor Medvedchuk, then Head of the Presidential Administration. [Medvedchuk's daughter's godfather is Vladimir Putin. He was accused of treason and handed over to Russia in a prisoner swap last year – ed.]

Koval wasn’t supposed to be the one reporting to the president according to the official chain of command, but the head of the State Border Guard Service (SBGS), Mykola Lytvyn (whose brother Volodymyr was the speaker of the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) at the time), had left on an official trip to Greece on 29 September, while his first deputy responsible for border protection, Pavlo Shysholin, had gone on holiday that very day.

Koval asked Medvedchuk to authorise the deployment of border guards to Tuzla and the reinforcement of the island’s defences. Medvedchuk hung up without answering.

Kuchma didn’t receive the reports from the State Border Guard Service until the following day.

Photo: Mykhailo Koval

By the time of the Tuzla events, Koval was already well-versed in resisting the Russians.

When he was the head of the 224th Air Assault Forces Training Centre in 1992, he prevented the 80th Air Assault Brigade (which was still subordinate to Moscow) from relocating from western Ukraine, where it was based at the time, to Russia. Russia had ordered the brigade to pack up its equipment and belongings and get ready to move to the Volga region.

Russia deployed two units of the Pskov Air Assault Division to Ukraine – "for help", it was claimed at the time – but Koval stopped them at the Cherliany airfield in Ukraine’s Lviv Oblast. He also got two Moscow generals who were supposed to oversee the brigade’s transfer to Russia arrested.

In 2003 Koval also showed himself to be a true combat general. The first thing he did was to deploy a group of Ukrainian border guards to Tuzla. This group came to be known as the "300 Spartans".

Koval ordered five regional chiefs of the State Border Guard Service to choose 30 "healthy guys" well-versed in both hand-to-hand combat and operating firearms and deploy them to Tuzla. To avoid causing a panic, he sent out a memo saying that an SBGS competition in hand-to-hand combat was to be held there.

This memo got quite a few people scratching their heads. When Koval was in Tuzla a few weeks later, he met a big guy who was crying like a child. It turned out that the Lviv department had decided to cheat and sent several athletes along with the actual border guards. One of them was crying because he’d thought he was going to a competition but found himself in a combat situation in truly Spartan conditions.

"I acted at my own risk," Koval recalls. "I had no orders [to prepare for armed resistance - ed.], but we do have a law on the state border, which clearly says that we have a right to use arms."

That was the beginning of his Battle of Thermopylae.

Three scenarios

Why did Russia want an island with a total area of 3.5 sq. km? There were several reasons.

First: economics. There is a man-made canal – the Kerch-Yenikale canal – between Tuzla and the Crimean Peninsula. The canal is used by ships passing through from the Black Sea to the Sea of Azov. With Tuzla under Ukraine’s control, Ukraine collects the fees from the passing ships, about US$6 million annually. If Russia seized Tuzla, it would claim half of this revenue stream.

Second: security. Controlling the island would have enabled Russia to control the Kerch Strait and, for example, block NATO ships from entering the strait.

Koval says that he considered three possible scenarios for how events might unfold.

First: Russia could have sent people wearing Cossack uniforms to Tuzla. Before the conflict started, Tuzla residents reported being visited by Kuban Cossacks who would try to persuade the local fishermen to return "to the bosom of great Russia". The Ukrainian border guards were preparing to repel the Cossacks with police batons, not machine guns, if they were to show up again.

Second: A combat scenario, with both sides resorting to firearms. Ukraine would still only be able to deploy its border guards, though, and not the armed forces, to avoid escalation to a full-scale military conflict.

Third: A mixed scenario, with Russia using the Cossacks to stage a false-flag operation before deploying its troops.

On 2 October, SBGS Head Mykola Lytvyn returned to Ukraine from his work trip. Koval flew to Tuzla that very day.

A place for real Kerch residents

What is Tuzla? A sandy spit stretching southeast to northwest. Ukraine designates it as a part of Kerch, not a separate settlement.

During Soviet times, the Sea Trading Port ran a guesthouse, the Two Seas, on Tuzla. There was also a sports and defence camp for kids there called Yunga (Ship’s Boy).

"If you walked all the way along the Middle Spit [as Kerch locals call Tuzla - ed.], you’d reach the very end, where you could stand with one foot in the Black Sea and the other in the Kerch Strait. Their waves would meet right in front of you. I’ve never seen anything like it since," says Olha Yurchenko, a journalist who covered the events on the island in autumn 2003.

Yurchenko recalls Tuzla’s special microclimate, the crust of bitter salt covering the sand on the shore (the name "Tuzla" is derived from the Crimean Tatar word for salt), and the ferry between Tuzla and Kerch.

"There was never any shade on the spit. It’s a wild beach. You have to be a true Kerch resident – someone who hates tourists with every inch of their body and wants to see no living creatures around – to want to holiday here," Yurchenko adds.

Kerch was rarely visited by tourists, politicians, or Russian and Ukrainian celebrities touring Crimea in the summer. The last time Kerch had appeared in the national news was in 1996, when members of the Kazinovski gang were shot and killed in a local nightclub.

This solitary and isolated island became the focus of the entire country’s attention in autumn 2003. An unwanted fame descended on the island like the rain and the northeastern wind – strong enough to blow your brains out, as the locals say.

Ukrainian and Russian journalists started gathering here in October 2003. So did politicians of every stripe. Kerch’s main streets were on the TV news almost every day.

Kerch residents were surprised, concerned and upset by the events unfolding around Tuzla, Yurchenko recalls, though they also talked a lot about the practicalities: what would happen to the fish if the dam was constructed; would it still be possible to holiday on Tuzla; what would happen to the guesthouse?

In reality, however, the first people to suffer from the territorial dispute between Russia and Ukraine were Kerch’s poachers. For Kerch, early autumn is the time when red-lip mullet and other fish are illegally caught on Tuzla. The reinforced security in the waters of the Kerch Strait made poaching risky, and the banned fish disappeared from local market stalls.

The fish would reappear soon after the end of the conflict – and Kerch would once again be gone from the headlines.

"Tanks" on Tuzla

While the Russians put in triple shifts to construct 150 metres of the dam every day, Ukrainian border guards were transforming Tuzla into a fortress.

Five pillboxes with machine gun emplacements were constructed around a spot where Russian paratroopers’ helicopters could have landed, and barriers were set up, turning this bit of land into a fire trap.

The marines sent every available ship from Balaklava to Kerch Strait, reinforcing the 23rd Kerch Sea Guard Detachment.

Using hydrographs, the border between Ukraine and Russia was marked with buoys from Tuzla to the Taman Peninsula; the border there had never been demarcated before.

The Kharkiv Aviation Squadron sent three helicopters to Crimea. Koval started up a sort of merry-go-round: the helicopters would hover over the border buoy opposite the Russian construction workers, one at a time. The insignia on the helicopters would be covered in mud, and the pilots changed their jackets and helmets before each flight – to give the Russians the impression that an entire helicopter regiment had arrived to support them.

The border guards drove two armoured floating transporters onto the island that had powerful tank engines and tracks identical to those of tanks. They camouflaged them as if they were real tanks, fooling not only the Russians but also some Ukrainians.

"The Russians contacted Lytvyn about these vehicles. He called me and said: ‘Mykhailo, why are there tanks there? This is turning into a military conflict rather than a border dispute!’ But I couldn’t tell him there weren’t actually any tanks there! ‘It just happened somehow,’ I replied," Koval says.

The State Border Guard Service gathered a powerful group of ground, ship, airborne and SBGS reserve units (about 300 border guards) and arranged with the motorised rifle regiment based in Kerch that it would provide artillery cover if the conflict escalated.

Koval recalls another phone call from Lytvyn on 10 October. This time, Lytvyn ordered him to stop everything he was doing and withdraw the border guards from the island.

"I told him: ‘Mykola Mykhailovych, you’re a pacifist. If I get an order in writing, I’ll comply. If not, I won’t.’"

Koval never received a written order to withdraw from Tuzla.

"God was watching over Ukraine that night"

Kuchma’s visit to Latin America began on 20 October 2003.

Why did the president leave the country in the middle of a crisis that was threatening to escalate into a military conflict? Kuchma says he kept demanding explanations from Putin up until the beginning of his visit, but Putin told him that it was an unsanctioned initiative by Alexander Tkachov, then the governor of Krasnodar Krai. The Russian president promised Kuchma he’d see to it. The construction of the dam slowed down.

"The dam had been progressing more slowly, and at one point construction had stopped altogether. Consultations were held at various levels. It seemed that the circumstances permitted me to make this visit, which had long been agreed upon and was important and extensive," Kuchma explains.

But as soon as the Russians got word of his departure, they picked up the pace – the dam was now growing by 5-6 metres every hour.

"The Russians worked very hard on the dam. It was like a living organism: the noise was constant, overwhelming. I bet they didn’t put that much effort into their Baikal-Amur Mainline," Koval recalls.

The dam was getting closer to Tuzla every hour. And then someone came up with the idea of creating a so-called Great Wall of China to obstruct the construction workers’ progress.

They found two lighters (barges used for transporting grain by sea), each 38 metres long. There was just one problem: the waters were too shallow for these barges to get in the way of the dam.

"And I swear God was watching over Ukraine," Kunitsyn says. "A storm had made a two-metre depression in the sand. We tied the barges up with cables, pulled them in, and put a border guard checkpoint on top, with a soldier guarding it with a machine gun.

When the Russians woke up next morning, they were furious. Where should the dam go next?"

Meanwhile, Kuchma had been trying to contact Putin. He did this on his way to Brazil on 20 October (he described the flight itself as difficult, with suspicious technical problems on his plane). The Russian president was on a visit to Thailand and could not be reached.

Kuchma kept on trying after he landed, but Putin continued to avoid having a conversation. After a meeting and talks with Brazilian President Lula da Silva (who ruled the country at the time and was re-elected in 2023 after a 12-year gap), Kuchma cancelled all his remaining engagements and flew straight to Crimea.

"I think if I had stayed even one more day, we would have lost Tuzla," recalls Kuchma.

"I was on my way to Ukraine by the time I finally got through to Putin. He pretended to be genuinely surprised, said he knew nothing about speeding up the construction of the dam and, as usual, promised to ‘sort it out’. Only that didn’t affect anything. We were flying to Tuzla."

"Are you going to shoot at the Russians?"

Kuchma went up to a sniper, a burly lad from the mobile border command post.

"Who are you, son? Are you going to shoot at the Russians?"

"I will shoot at any violators of the state border."

"Can you do that?"

The sniper showed him a coin with a hole in the centre that he was wearing around his neck and said, "I hit like that from a hundred metres."

Mykhailo Koval recalled this story about Leonid Kuchma's stay in Tuzla.

On 23 October, the Ukrainian president finally reached the island of strife. He was joined there by Viktor Medvedchuk, the head of the President’s Administration, Mykola Lytvyn, the head of the State Border Guard Service, security forces and Crimean leaders.

Koval reported on the situation. There was a grave silence.

"There have been several times in my life when people have looked at me as if I was doomed. And that was one of those times," says Koval.

"Everyone realised that in the worst-case scenario – if they fired – the Russians would kill us on the island. Our possibilities for manoeuvre were limited, and the fortifications were not that powerful. Russian rocket artillery would have burned everything up, and us with it."

After the meeting, Kuchma and Medvedchuk got into a UAZ [off-road vehicle] and went to see the island. Koval set off after them on a red motorcycle.

When they reached one of the fortifications, Koval suggested that Kuchma go down into a pillbox.

"They came down after me – the president and Medvedchuk. They saw five embrasures, each with a machine gun, grenade launchers standing with grenades, and a lot of people, everyone ready for battle," says Koval. "They saw all this and they both felt embarrassed."

But the excursion didn’t end there. Koval showed them another part of the island where there were "hedgehogs", mines and warning signs in Russian.

"When Kuchma saw this, the expression on his face changed. Maybe Lytvyn had misinformed him, but he saw a completely different picture than the one he’d expected. He saw the island armed to the teeth and the people ready to defend their land.

And he immediately told Medvedchuk, "I’ll call Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin]." He moved a few metres to the side, called Putin and spoke with him for a few minutes. And then he turned to us and said, ‘That's it, they’ll stop now. Let's sit down at the negotiating table.’"

Kuchma told us about one important detail of this conversation. He warned Putin that he had given the order to open fire on violators of the border.

The Russians halted the construction of the dam that same day.

It was a hundred metres away from Tuzla.

"Where the chicken leg doesn’t turn black, that’s where you should build the border post"

"Kunitsyn from Tuzla". That’s what Serhii Kunitsyn says they called him in Moscow when he arrived there in military uniform for the negotiations.

"Did they think I was going to turn up in a bowtie to play the violin or something?" he says.

On 24 October, a Ukrainian delegation headed by Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych went to the Russian capital to discuss the status of the Azov-Kerch region at a meeting with Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov. Kunitsyn was there too.

"We flew to Moscow and went to the White House. Chernomyrdin [the Russian ambassador to Ukraine – Ukrainska Pravda] was a dreadful sight. It was clear that he hadn’t been warned about the construction of the dam – they just dumped him in it. He was so pale he was almost white," recalls Kunitsyn.

According to Kunitsyn, the Ukrainians played two wild cards at these negotiations. The first was the 1973 election ballot papers for Kerch City Council, which evidence that the streets of Tuzla belonged to Kerch. The second was some maps of the General Staff of the USSR that showed the border between Russia and Ukraine passing between Tuzla and Kuban.

Once the negotiations started, the Ukrainian border guards began to dismantle the concrete bunkers and remove them from the island. And Mykhailo Koval began to look for the best location for a stationary border post in Tuzla. To do this, he bought some chicken legs.

"A Crimean Tatar advised us to take some chicken legs and hang them in different places. ‘Build the border post where they don't turn black,’ he said. I did just that, and it worked out very well," he recalls.

Koval arrived in Tuzla on 2 October and ended his long assignment on 25 December. By the time he left the island, there was a powerful border infrastructure, a border post and houses for the officers – all built with the help of railway workers.

"We handed over the section of the border to the full-time border unit, solemnly raised the flag, and quietly left," says Koval.

"I then personally told my ‘Spartans’ that all of them, down to the last soldier, would be rewarded. And I kept my word – they all received awards, wherever they were."

So what became of the dam that Russia had been building?

In 2005, journalist Olena Yurchenko was in Taman and out of curiosity, she visited this unfinished Russian structure. She saw a dam made of monumental blocks, with locals swimming among the huge rocks, and was reminded of the title of a novel by C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength.

"Despite the rocks and the difficult descent to the water, a lot of locals were swimming there with their children. They’d parked their car, dad was eating watermelon, the children had meatballs…" she says. "It was disgusting. So many resources and efforts were invested there. And how did it end? With people eating meatballs on the pier?"

"They’ve gone beyond their obligations and moved on"

The "Year of Russia in Ukraine" began in Kyiv with solemn speeches about "the nobility of thoughts and the greatness of aspirations". And it ended on 24 December in Kerch, where Presidents Kuchma and Putin signed an agreement on cooperation in the use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait. The Sea of Azov was designated as an internal sea of the two countries. Foreign ships may only enter it with the consent of both parties.

"The Russian side once again got what it really wanted, and Ukraine, as usual, lost its tasty wedge of cheese. Even without completing the dam to Tuzla or revisiting the border issues, Russia has carved out the strategic and economically beneficial Kerch Strait for itself, and the Kerch-Yenikale Canal too." That was how one column in an anti-Kuchma media outlet described the outcome.

The Ukrainian president stated at a press conference that the parties had "gone beyond their obligations and moved on".

"The Tuzla issue was not discussed. There is no such problem in Russian-Ukrainian relations," Kuchma said.

Was there any possibility that the construction of the dam was an initiative of the Krasnodar Krai leadership and not a Kremlin-sanctioned provocation?

Here’s how Leonid Kuchma answers this question in his book After Maidan: Memoirs of a President, published in 2007.

"I don't think the command was given directly by Putin. It is unlikely that he was privy to the plan and its details. Perhaps, after listening to the plan’s initiators for a while, he waved his hand, and this gesture could have been interpreted in two ways: either ‘Get away from me with this petty issue,’ or ‘I agree. Do it.’"

And here’s how Kuchma's answer to the same question looks in September 2023 – spot the difference.

"Can you imagine a local leader who, on his own initiative, starts to construct a ‘district-scale’ structure that will involve crossing two lines of the state border, completely undermining the legal status and shipping regime of a strategic sea strait, and ultimately adding part of another country’s territory to his ‘fiefdom’ - in an incomprehensible way and with unpredictable consequences?

If you can imagine that, then guess how many metres would have been built and how many minutes would have passed once Putin, who was ‘not involved’, found out about it."

Echoes of Tuzla: conspiracy theories, erotica, history

Tuzla continued to excite the imaginations of politicians and artists for some time after 2003.

Conspiracy theories were, of course, inevitable. According to one of them (particularly promoted by Ivan Pliushch, an MP from the Our Ukraine party), Tuzla was a scenario cooked up by jointly the Kremlin and Bankova Street with the aim of preventing the 2004 elections in Ukraine.

The plan supposedly went like this: Russia would cross the state border of Ukraine. The beginning of an armed conflict would be simulated. Kuchma would dissolve the Verkhovna Rada and explain in an address to the people that presidential elections cannot be held in such a situation.

As well as conspiracy theories, Tuzla also evoked powerful erotic experiences. Oleksandr Irvanets [a Ukrainian poet, writer, playwright, and translator] wrote the following lines:

You won’t catch any morals here

Or any sanity either.

Protect your tuzla, girls,

While you still have it.

A musical based on the events in Tuzla came close to being staged. The plot was as follows: a young Russian guy, an excavator operator, digs up the ground in order to get closer to a beautiful island girl. The musical ends with the island girl singing an aria: "You could take me, but not Tuzla."

The libretto was to have been written by Russian propagandist Dmitry Kiselyov. Back in 2003, he hadn’t yet started threatening to "turn the USA into radioactive ash", or calling for "gay people’s hearts to be burned", nor was he the head of Russia Today, but he used to travel to Kyiv to earn money. At that time, he was editor-in-chief of the news department of the Ukrainian television company ICTV, hosted a socio-political talk show, "The National Interest", and received a decent salary from Viktor Pinchuk, owner of the channel and Leonid Kuchma's son-in-law.

"If" is a word unknown to history. But to some extent, the Tuzla standoff of 2003 allows us to imagine how events could have turned out if Ukraine had been determined to fight back against Russia in Crimea in March 2014.

"At Tuzla, Ukrainians were the first people in the world who had ever forced Putin to stop and retreat. But Tuzla did not serve as a lesson and a model for Ukraine in 2014," Kuchma believes. "I don't remember ever feeling such burning shame for my country as I did in the spring of 2014, when the ‘little green men’ forced our soldiers to their knees and took our Crimea silently, without firing a single shot."

What does the Tuzla epic look like through the eyes of a historian 20 years later?

According to Serhii Plokhy, director of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, for Putin, Tuzla was an overture to the 2014 war. It was his first attempt to change the rules of the game, to resolve an issue not through diplomatic pressure on Ukraine, as happened in the 1990s, but through direct action and attempts to violate international borders.

"Russia concluded back then that you can’t achieve much with bulldozers alone. And the result of that was 2014. But since 2014, they have drawn the wrong conclusions, hoping eight years later for a blitzkrieg, Ukrainian passivity, and ‘deep concern’ the only reaction from the rest of the world.

And with Ukraine, everything is the other way round – Ukraine absolutely did not draw the conclusions it should have drawn after Tuzla. But it has drawn the right conclusions since 2014. Otherwise, we simply wouldn't be having this conversation today."

"You will not be forgiven for Tuzla"

"Victory always has many parents. On the island of Tuzla, I said to my ‘Spartans’, ‘Men, when all this is over, we will be standing far, far behind, and at the front, there will be people who knew nothing at all about what was happening here.’ What’s more, in the end they will make us scapegoats. And that's what happened," recalls Mykhailo Koval.

When Koval returned to Kyiv just before the new year of 2004, he was awarded the Order of Merit, 3rd class, for Tuzla. But not in front of his comrades-in-arms in formation, but "under the Christmas tree". And then it was immediately suggested that he resign from the army. He is certain that it was purely because he refused to take people out of Tuzla.

"My response to Lytvyn was: ‘Mykola Mykhailovych, I do not serve you, but the Ukrainian people.’

For a year, they put intense pressure on me from all sides. They couldn’t fire me, because my subordinates treated me well and never let me down."

However, unlike Ukrainians, the Russians did not forget Tuzla, or Koval's role in its defence.

In 2010, Defence Minister Mykhailo Yezhel offered Koval a position leading the special operations forces that were about to be set up. Koval described their structure, and the documents went off to be signed by the president.

"Some time later, Yezhel calls me and says, ‘Mykhailo, this structure will not exist, and you will not be appointed.’ ‘Why not?’ I said. ‘Moscow does not approve. They will not forgive you for Tuzla.’

I said: ‘Mish [short for Mykhailo], are we still ruled by Moscow?’"

In the same year, 2010, General Koval was invited to Moscow for a celebration of the 20th anniversary of his graduation from the Frunze Military Academy. General Ignatov, already the Chief of Staff of the Airborne Forces of the Russian Federation at that time, was also there. Seven years earlier, he had been preparing a battalion of Russian paratroopers to land on Tuzla.

Koval’s former fellow students – Russian soldiers, most of whom had Ukrainian roots – asked him: "Would you have shot at Ignatov?"

"I would have shot at any violator of the state border of Ukraine," Koval replied, repeating the phrase he had heard on the island from the young Ukrainian border guard.

Four years later, in March 2014, Koval was captured by Russian paratroopers in Crimea. And when he was released, he received a late-night phone call from Vladimir Shamanov, Commander of the Airborne Forces of the Russian Federation and another fellow student of his from the Moscow academy, with whom he had later served.

"‘I'm sorry, pal,’ he said. I answered, ‘This is a war, and we aren’t pals.’"

***

The "Tuzla standoff" would make a great blockbuster – whether a heroic epic about this modern-day Thermopylae and the 300 Spartan border guards, or a political thriller, or a prequel to a drama about the full-scale war.

In April 2016, the Russians installed the first of the 595 supports of the Kerch Bridge on Tuzla itself.

On the night of 17 July 2023, after an attack by Ukrainian surface drones, the Kerch Bridge "got tired" again. [The phrase "The bridge got tired" was first said by the mayor of Kyiv when one of the bridges in Kyiv was damaged in February 2017. This classic phrase has been used when talking about ruined bridges ever since.]

This time, a span of the bridge fell near Tuzla.

To be continued. The next chapter of this story is being written right now.

Mykhailo Kryhel, Rustem Khalilov, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Olya Loza and Elina Beketova

Editing: Teresa Pearce