"We’re basically peacekeepers. But you are all f*cked…" 35 days of the Russian occupation of Obukhovychi village - from tragedy to farce

On 24 February, a linguist, a philosopher, a lawyer, a financier and a 14-year-old teenage Banderite gathered under the roof of an ancestral house in a remote village near the Chornobyl zone and the Belarusian border.

They would not be able to leave this place until 7 April.

This plot can be deployed in any way and for every taste. From tragedy to melodrama, from horror movie to fairy tale.

This is the story of how three generations of one family survived under Russian occupation.

It’s about the fragility of a person who is protected in peacetime by work, social ties and bank cards. And how in the blockade, all of that collapses like a house of cards.

It’s about how quickly we begin to be ruled by primitive fears - death, famine and destructive fire. And how to prevent these fears from driving us crazy.

This is about flashbacks to the Second World War, which turned out to be more alive than ever.

Last of all, this is about the sense of humour that saves us when the other six senses are sound asleep.

Is this a story about war? It’s more about why we are gnawing every metre of our land from the enemy for the third month.

And it’s also about how long the journey home could be.

Scene

The village of Obukhovychi in Kyiv oblast. It’s about 100 km to the capital and 10 km to Ivankiv, the district centre.

The main characters

During the 35 days of the [Russian] occupation, Svitlana Musiienko turned from "Tax Lawyer of the Year" and hedonist into a stoic, guardian of nature and "minimum-level looter". When she had any time to spare from the struggle for survival, she would go into the forest to talk to a pine tree.

Svitlana's husband is a financier. During the occupation, he formed coalitions with neighbours to obtain petrol for the generator.

Svitlana's mother-in-law is a professor of linguistics. A native of Obukhovychi, she knows the cultural code of the village - how, with whom and what to talk about to buy or exchange food.

Svitlana's father-in-law was born in 1945 and is Austrian by nationality; he was deported from Austria by Soviet troops. He was brought up in an orphanage in Western Ukraine and is a Doctor of Philosophy.

Svitlana's son is a 14-year-old teenager. A young Banderite. Due to his inexperience, he is fearless. During the occupation he would write stories in English on "How I Hate Russia", "Where will I go when all this is over?" and "What would I eat?"

Yevgeniy the political instructor is a Russian occupier who tried and failed to find Ukrainian authorities in Obukhovychi.

The Ukrainian authorities are present in Obukhovychi but invisible.

The pine tree Svitlana talks to is a witness of the Second World War.

Seneca is a Stoic philosopher, an imaginary friend of Svitlana’s. He took part in her conversations with the pine tree.

Residents of Obukhovychi have survived dekulakisation, the Holodomor, Stalin's repressions, the German occupation, the Chornobyl disaster, and the Russian occupation.

What follows is Svitlana Musiienko’s story exactly as she told it to Ukrainska Pravda.

Act one: road movie

Life without an agronomist, dollars in a can, a change of values, flour and petrol are the new currency

Obukhovychi is a typical Ukrainian Polissia [woodlands] that flows on into Belarus.

The locals speak their own dialect. The words "kin" [horse], "viz" [cart] and "stii" [stop] in Ukrainian are pronounced "ken", "vez" and "stei" in Obukhovychi [there is one letter difference in pronunciation].

The people who live here are very practical and down-to-earth. This is a small commune where everyone knows everyone else, down to the third or fourth generation.

There was a saying in Soviet times: "Four rains in May - the agronomist can f*ck off away." This is the essence of the local psychology; at least, that’s how I (a city girl) see it.

It’s important to have your own potatoes, your hens have to lay their eggs, your cow has to give its milk, you need to sow your own wheat. Independence multiplied by natural farming…

On 24 February, at 9 am, we left our Kyiv apartment and headed for Ivankiv. Our "go-bag" was packed with documents, medicine and money.

By evening in Obukhovychi, where we had come to escape from the Russians, the Russians were already there.

Our first fears were still urban: Help, we’ll be robbed!

We rushed to save our money. We wrapped our dollars in foil, put them in a can, and hid it in a village toilet. A day later, my father-in-law the philosopher said, "You didn’t pack them properly. They’ll get wet." We repacked them. By the end of the occupation, they were still in the toilet.

But we quickly realised that there was something else we needed to be afraid of. It turned out that you can easily do without everything that had been valuable in Kyiv - apartments, cars, new jewellery by Cartier.

I changed my mind instantly. In this new life, there was nothing more important than miraculously obtained flour. Because that meant that hunger would end for a while.

There was no electricity, the boiler didn’t work, and the radiators didn’t heat up. But we needed all that about as much as they needed the agronomist in the saying. Because there was a stove, firewood and water in the well.

And there was a mother-in-law who knew how to bake bread from homemade yeast and any type of flour.

Act two: historical reconstruction

The important Hebes, "Germany is stirring," the Russians are the new Germans

We have many strange expressions in our family. My mother-in-law often used to say, "Look how he drives, he’s as important as Hebes." I asked what that meant. It turned out that Hebes was the name of a petty official during the German occupation of the village.

There is still [the saying] "Germany stirs". What does it "stir"? Why is it "stirring"? On the eve of World War II, some men were sitting around near a village club and one of them was reading a newspaper. When asked, "What do they write?", he replied, "This is Germany stirring."

As soon as the Russians entered the village, people began to call them Germans straightaway. These were the typical German occupiers shown in Soviet cinema, who went from house to house with machine guns and demanded "eggs, milk, chicken".

We immediately remembered the stories my husband's grandmother told about how the Germans were standing in their house. She was 16 at the time. Grandma said they were still "more or less decent". Not all the milk was taken away - each child was left with a mugful.

They weren’t Germans, however, but Austrians. Ever since then, she has considered Austrians to be decent people in general.

Act three: surreal

Decentralisation and Zen of Ukrainian officials, the old woman and the infantry fighting vehicle, the manifesto of Yevgeniy the political instructor

Having occupied the village, the Russians began to seek out Ukrainian officials.

They searched in vain. You can't find what simply is not there. There is decentralisation. The village is now part of the amalgamated territorial community of Vyshhorod district. All the authorities are somewhere far away.

There is a club, a couple of shops, and a paramedic station that closed during the occupation. They have never had any officials.

As they had failed to seize power in the village due to its absence, the Russians rounded up the locals and made them go to a meeting. It looked like this: a grandmother, leaning on a stick, limping along the road, followed by a Russian infantry fighting vehicle slowly adjusting to her pace.

They gathered the people together and demanded that they elect a сhief. A chief! The villagers looked at each other with understanding - they had immediately caught the word from the time of the German occupation.

The people refused to elect a chief, saying that they had a legally elected secretary of the village council. But they didn’t want to say where she was. Later, however, someone gave the secretary away [to the Russians]. And they came to her in the same infantry fighting vehicle. They tried to hand over some humanitarian aid. She replied: "We don't need your stuff. We have our own potatoes and cucumbers."

Yevgeniy the Russian political instructor delivered a speech to those present at the meeting.

"We’re basically peacekeepers", he said. But if so much as one hair falls from the head of a Russian soldier, you're all f*cked. Live however you want. We won't touch you - and you won't touch us. Only don’t go outside the village, wear white armbands when you’re out and about, don’t walk in the vegetable gardens, and put lists of the inhabitants on the gates of your houses - we’ll check."

Act four: family saga

The Good Soldier Švejk in Russian captivity, Tolstoy's test, the hatred of salvation, the fear of hunger and the joy of reading

On 5 March, electricity and the mobile networks disappeared. We waited a few hours and realised it would be for a long time. Maybe forever.

For a while, the workings of his thoughts were visible on the face of my son, who had been deprived of the Internet by the invaders. Then he asked, "Mum, what are we going to do?"

I took his hand, led him to a room which contained books, pulled out a random book and said, "Enjoy!"

It was The Good Soldier Schweik [Švejk] in Captivity. My son opened it and began to read. Four minutes later I heard a grunt that turned into laughter. It was the episode when Schweik, who was suffering from rheumatism, rode out in a wheelchair and shouted, shaking his crutches, "To Belgrade!"

After our young "Bandera man" lost his digital paradise, he suffered under the burden of the need to study. Unfortunately for him, there were algebra and geometry textbooks in the house. He improved his French by translating War and Peace.

After yet another test by Tolstoy, he came to us and cautiously asked, "I seem to hate the Russians. Do you think this is bad, or normal?"

My mother-in-law was the central figure in our blockaded life. She unleashed all her economic wisdom on us and deprived us of the slightest chance to escape.

I fell at her feet and took an accelerated course in being a Bereginya [according to Slavic myths, she is a protector of nature and the hearth of the family].

Peeling potatoes or patching pants is a great meditative practice, especially when nothing depends on you except the potatoes and the pants.

The two main emotions I lived with during these 35 days were the fear of hunger and the joy of reading. Hemingway, Romain Rolland, Dostoevsky, Somerset Maugham, biographies of Einstein and Napoleon - about forty books in the home library.

And I peeled more potatoes than I had in the previous 25 years of married life.

Act five: alternative reality

Where does news come from, "One Woman Said", From the "DPR" to Ivankiv: "Peace to your home", seamstresses from Ivanovo

Local news becomes vital in occupation. The rest of the country is living its own life, which is very different from yours.

No, we didn't think we had been abandoned. It seemed that we could only save ourselves if we took care of ourselves.

The news in Obukhovychi was mostly in the "OWS" [One Woman Said] genre. Someone would sneeze at one end of the village, and an hour later at the other end they’d be saying that he’d come down with Covid.

Among other channels, our [satellite] "dish" picked up Russia’s Channel 1 [Pervyy kanal, a Russian state-controlled television channel] when there was still electricity. As Ukrainian television did not make us happy with information about humanitarian corridors, we decided to listen to see if the "we-are-brothers" [Russians are always insisting that Ukrainian and Russian people are brothers] were saying something "locally informative" about us.

Guess what? We watched a story about how a car full of humanitarian aid supposedly came to Ivankiv from the "DPR" [self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic]. "Peace to your home" was written on the car.

I don't think that Russian viewers would have been surprised by the logistics - the fact that a car carrying humanitarian aid had made its way to Ivankiv through the whole of war-torn Ukraine from the "DPR" [self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic].

In general, Russian TV channels were an endless source of black humour for us during the occupation. We rejoiced when we heard that the seamstresses of Ivanovo [a Russian city northeast of Moscow] had invented a new way of economical cutting. We sincerely wanted these seamstresses to sew as economically as possible.

Act six: melodrama

Being fed with red guelder-rose, the pine tree, Seneca and the fear of death

"Svitlana’s gone to her pine tree again", they would say at our house.

The pine tree grew 400-500 metres from the house. It was very tall and very old. I don't know how old it is, but I don't think this is its first war.

I needed someone to talk to who was silent, calm and wise. Twice a day my husband accompanied me [on the way] to this tree. As we walked, we ate guelder-rose. First, it's romantic: "Darling, let's go for a walk, I'll feed you with guelder-rose." Second, it’s good for your blood pressure.

While I talked to the pine tree, my husband guarded our solitude. My husband is very pragmatic, very down-to-earth. But he never once asked me, "Listen, what are you doing here with a pine tree?"

I talked about Seneca with the pine tree. I would recount the "Moral Letters to Lucilius". I remembered from Seneca that the fear of death is the father of all fears. The same was true of the fear of hunger that had haunted me from the very first days of the blockade.

I honestly shared with the pine tree everything I had - my fears and Seneca.

The pine tree made no objection. It remained silent and agreed with everything.

Act seven: a fairy tale

Baba Yaga and female initiation, a fairy-tale burrow and relaxed cats

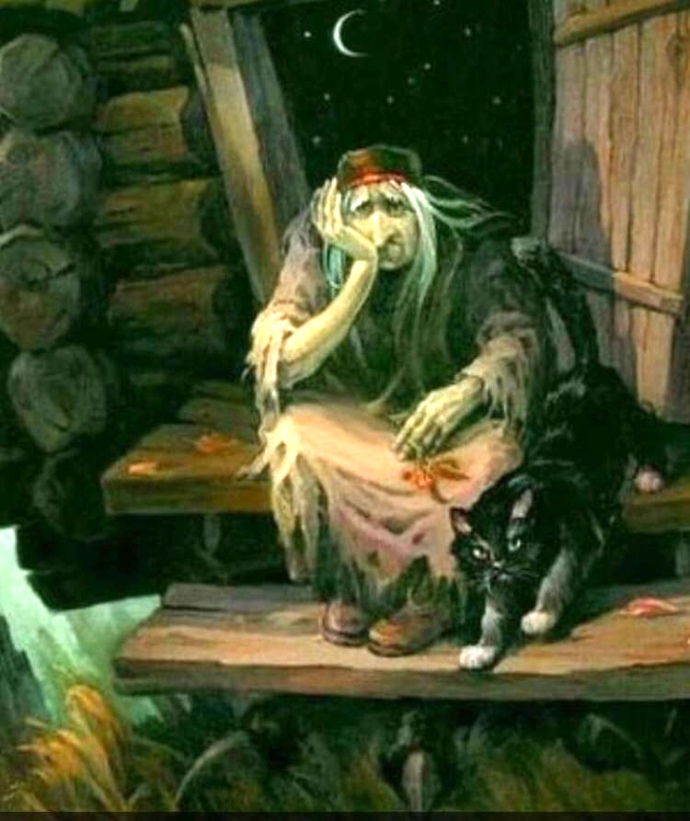

My inner state during the occupation is best conveyed by two images.

The first image is of Baba Yaga sitting on the porch of her hut. She is wise. She has seen it all. She knows everything about anger, death, fear, love, blood. About everything.

Before the war, I reread Women Who Run with the Wolves by Clarissa Pincola Estes, a collection of tales about the archetype of the ancient woman.

One of the fairy tales is about Vasilisa [the Beautiful] and Baba Yaga. Vasilisa comes to see Baba Yaga, and Baba Yaga gives her a glowing skull. Then the heroine has to learn not to be afraid of life, to clear her mind of trivial things, to bring order to her thoughts and feelings. She has to kill the girl inside of her who is too good to learn how to react to aggression.

This is a tale of female initiation. And that was my story in the occupation.

Now I know for sure that this Baba Yaga is within me - strong, invisible and omniscient. I even looked for a stump in the woods to sit on and complete the image. But a stump next to my pine tree could not be found, and I was afraid to go further into the woods; there could be mines.

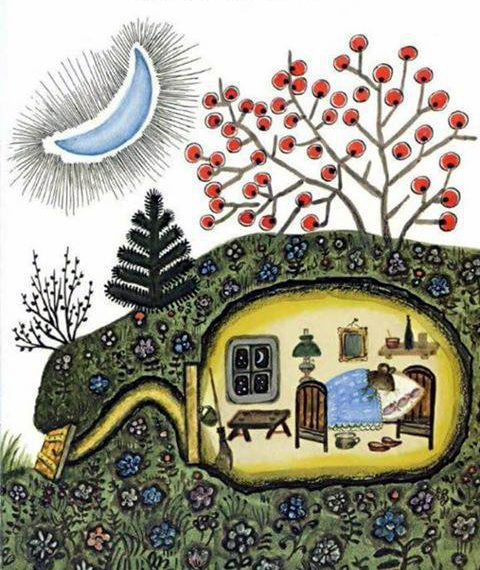

The other image is of a fairy-tale burrow. That was how I imagined our house to be, to persuade myself that we were safe, we could relax and fall asleep, despite the Russians 500 metres away from the house and the artillery fire at night.

Feed yourself and your family, feel the warmth and safety, if there is no rocket over your head right now. Are your feet warm? They are. Are you sitting on a warm bed? Yes. Well, relax then, you fool!

And you relax. We are no longer city dwellers who get stressed out for no reason. As long as there is no cast-iron reason for stress, we are as relaxed as cats.

This is a precious skill that I want to hold onto in postwar life.

Act eight: tragicomedy

"Minimum-level" looting, two packets of flour, toothpaste and Mozart liqueur

We have a neighbour, a friend of my mother-in-law’s. When the war started she was outside the village, but she told us on the phone, while there was a connection, that we could take her food supplies and whatever we needed from her house.

Once my mother-in-law passed by her house and saw that the locks were broken. In the village there was sometimes looting. We don’t know who did it - the Russians, or the local drunk looking for vodka.

Anyway, it was right in the middle of the Russian occupation, and we had nothing. I said: let's go over there, we’ll fit new locks and have a look at the same time, maybe we'll find something useful.

We went into the house and began to search. My mother-in-law, with a battle cry, rushed over to two packets of flour. I looted half a pack of ground coffee and shoved teabags into my pocket. I rushed to the bathroom and found three tubes of dried-up toothpaste.

I fancied a small bottle of Mozart chocolate liqueur. I’d brought it from Vienna eight years ago as a gift for my mother-in-law. My mother-in-law gave it to her neighbour. She didn't drink either, but she decided that it was a good thing that was needed in the household, and put it in the cupboard. And years later, the liqueur came back to me.

We came home, laid out all this treasure on the table and laughed together. How the things that made a lawyer and a linguistics professor happy had deteriorated.

That was how I discovered within myself a "minimum-level" looter - one who carefully noted down everything that she looted in order to compensate the neighbour later on.

Act nine: the horror

Theatre of war, a gap in the blackout, a trench for future cleansing

Night. I'm sitting by the window. There’s a blackout, but I drilled a small hole to watch through. Aircraft, bombs, artillery, red signal flares. And you realise that there is nowhere to hide, there is not even a cellar. You sit on the floor and watch this unreal theatre of war.

Compared to others, our village was lucky. The Russians destroyed only a few houses and burned one.

I have no explanation for this, because there is no logic. In neighbouring Termakhivka, 4 kilometres from us, half of the village is missing, and there are graves in the vegetable gardens.

When they left, we found a deep, long and strangely shaped trench. Locals decided that they had been digging it for future cleansing. There were Joint Forces Operation members and their families in the village. But right before they left, the Russians were no longer up to dealing with them.

The occupiers left dug-up, raped land, heaps of rubbish, piles of shit, and an icon - most likely stolen from one of the locals - at the checkpoint.

The ground was scorched in the places where their [Russian] tanks had stood. Today, grass grows everywhere except those patches. Wire is stretched across the fields. The cemetery is mined.

Abomination is the word that most accurately describes what happened. After their withdrawal, I wanted to disinfect it all.

Act 10: Road movie again

Getting out of Obukhovychi, and returning, the first hot dogs, the long journey to yourself

We left the liberated village by car. There was no road, the bridges were destroyed, and it was impossible to cross on the pontoons. Instead of going south to Kyiv, we headed west to Zhytomyr oblast.

We arrived at the petrol station in Radomyshl. My husband ran to refuel and returned with a shout: "There’s petrol!" My mother-in-law darted over and came running in amazement: "There are hot dogs!" She gave me the hot dogs and ran to the next store. She ran out of there, squeezing a bag of flour to her chest. She shouted, "There is flour!"

The sales assistant at the petrol station cried when she learned where we had come from, and gave my mother-in-law some sunflower oil to go with the flour she’d bought. My mother-in-law was happy…

I have been married for 25 years and all these years my husband has been taking me to his family nest. I always treated it… how can I put this, so as not to offend anyone... I was polite. I knew he was happy there, and I went there with him.

On 7 April, we left liberated Obukhovychi, and on 24 April we returned to celebrate my husband's birthday. Because it had become clear where we wanted to share this day, and with whom.

I have Ukrainian, Russian and Jewish blood, and even a little Latvian, it seems. And only now has everything come together.

My little homeland was around me all the time, quiet and beautiful, but we did not have the same configuration. And now we do. It was as if I had found the key to a home. And all those symbols of Ukrainian Polissia - storks, pine trees, snowdrops in the woods, chickens in the mud - became close to my heart.

It took me 25 years to let this small corner of Ukraine into my heart. And 35 days of occupation.

***

"I never used to swear before the war. But [I started doing it] during the [Russian] occupation and immediately after - constantly. Where did it come from? Such an intelligent girl. A lawyer. And here it is", says Svitlana Musienko regretfully.

Today she is near Stockholm. There are many pine trees there - but not like the ones in Obukhovychi. They know nothing of war. They are interested. Svitlana does not reject any of them.

"I think we need to preserve our humanity - despite everything, despite the understandable hatred of the enemy. To be bigger than them. Not to give them a chance to dehumanise our struggle and our future victory.

And we need to try to become fearless. Let's take small steps. This is what I tell myself every day. It doesn’t always work, but I'm trying.

The worst starts with fear, Seneca said. I believe him."

Mykhailo Kryhel, Ukrainska Pravda