What happened in Russia's Kursk Oblast during the last month of defence

In early March, a group of Ukrainian reconnaissance troops, following their commanders' orders, moved from their positions near the Russian town of Sudzha closer to the Ukrainian border. Ukrainian troops controlled approximately 350 sq km of Kursk Oblast at the time, rather than 100 sq km as they do currently.

The distance they had to travel from point A to point B was about 15-20 km. It took them two days, including hiding from FPV drones and taking rest stops.

"The bus was no longer running, so we had to walk," a soldier from the group with the alias Maiak joked to Ukrainska Pravda. Maiak sustained a muscle contusion during the withdrawal.

"F**king Kursk," was how another soldier, a foreign national with the alias Gangster who has been fighting for Ukraine since 2022, described the route.

Most of the time the group moved at night, hoping the Russians had fewer night drones than daytime ones. But there’s a major downside to travelling in the dark, the guys say: you can't fire at an enemy FPV when you can't see it.

Covering this huge distance wasn't a one-off. Maiak and Gangster and their comrades – reconnaissance troops from one of the strongest brigades in the Ukrainian army – had been moving to positions this way for the past month.

The order to move closer to the border, which they received in early March, didn't signify the beginning of the Ukrainians' withdrawal from Kursk Oblast. That was still a few days away.

But the order was related to one of the catalysts for the withdrawal – the Russians had broken through the Ukrainian defensive line south of Sudzha and were rapidly approaching the defence forces’ field supply and evacuation routes in Kursk Oblast.

By chance, and without knowing it themselves, Maiak and Gangster were to hold these roads, their comrade told UP. Otherwise the Ukrainian troops risked being surrounded on Russian territory.

"They don't tell you 'Go and hold the road.' They say: 'The bearing is such-and-such, open the map and go to that point'," Gangster later told UP.

A few days after UP heard the story of Maiak and Gangster's group, we learned they had already returned to Ukrainian territory and other soldiers had replaced them in that critical position. So their mission had been accomplished. As of 20 March, Ukraine’s defence forces still have entry and exit routes to and from Russian territory.

Ukrainska Pravda was one of the few media outlets that were able to get to Sumy Oblast in the past week and work near the Ukrainian-Russian border – in the villages of Yunakivka, Mohrytsia and Myropillia. We also spoke with around twenty soldiers and commanders from four units involved in the Kursk operation. Here's what we learned.

*The defenders’ aliases have been changed for security reasons.

The protracted and weakened defence of Kursk Oblast

The Ukrainian troops in Kursk Oblast didn’t find themselves in challenging defence conditions overnight. Since autumn 2024, there had been problems with logistics, communications and a lack of experienced infantry able to hold the positions the paratroopers had gained. And these problems, UP sources say, had been ignored by the command of the Kursk military group, which since the autumn had been assumed by the Air Assault Forces Command.

Read more: Six months in Kursk: the problems facing Ukraine's defence forces

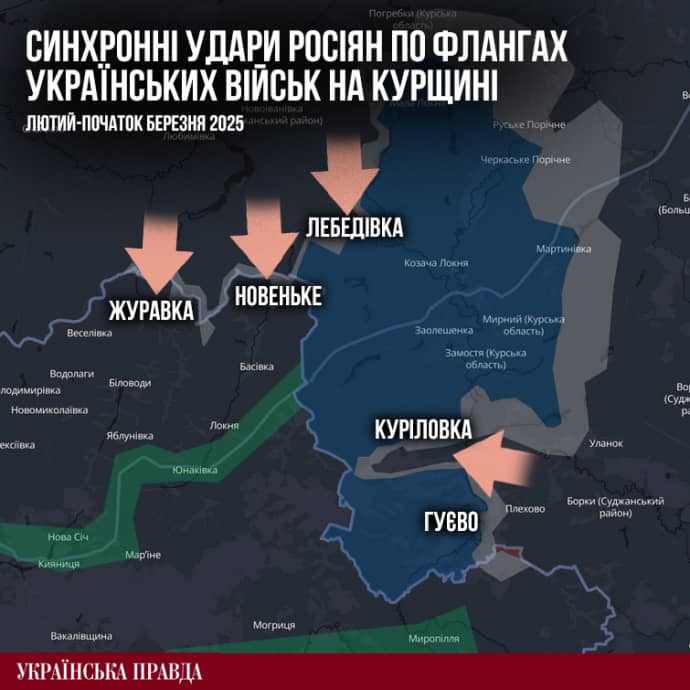

Ever since the Russian forces launched their counteroffensive in Kursk Oblast in September 2024, they have primarily attacked the flanks.

The Russians almost immediately pushed the Ukrainian troops to the left of the road to Sudzha, into the area of the villages of Glushkovo and Korenevo. Then, each month they chipped away at the Ukrainian salient, pushing the defence forces closer to the main supply road (Sumy-Yunakivka-Sudzha).

To the right of the road, the situation was slightly better. However, here too, Ukrainian troops had to retreat closer to Sudzha and the main road in November and December 2024, leaving the area near the settlements of Borok and Plekhovo.

Most of UP’s sources from the officer corps believe that the operation's command made a mistake by placing weaker units on the flanks of the Kursk salient while the stronger ones, including the 95th, 80th and 82nd Air Assault Brigades, were left in the centre of the Ukrainian salient, on the railway towards Lgov and the road towards Kursk.

The soldiers UP spoke to also had mixed feelings about the command’s decision to conduct offensive actions towards the village of Bolshoye Soldatskoye in early January. This is along the road leading from Sudzha to Kursk. After all, in this way, Ukrainian troops were dragging themselves deeper into Russian territory rather than rescuing the flanks, which were constantly narrowing.

The Ukrainian forces later decided to expand their right flank and pushed the Russians 3-5 km away from Sudzha. However, this had no significant impact on the situation.

The more Ukrainian forces retreated on the flanks, the closer the Russians and their drones got to the Ukrainians’ main logistical artery – the Sumy-Yunakivka-Sudzha road.

The situation for the Ukrainian group got even worse in early January 2025, when the Russians began flying large numbers of drones above the road using fibre-optic technology that could not be jammed by electronic warfare. Every pickup truck heading to Kursk Oblast – and even more so, every armoured vehicle – risked being hit or burned.

In its report on the problems faced by Ukrainian troops in Kursk Oblast in early March, UP published photos of vehicles in flames near the border.

The last time the units that spoke with UP drove pickup trucks into Kursk Oblast was around late January or early February. At that time, it was still possible to drive to even the northernmost points of the Ukrainian salient, including the areas around the villages of Malaya Loknya and Russkoye Porechnoye.

Later on, the drill became: drive the pickup to a frontline Ukrainian village and then continue on foot, crossing the border and walking to your position, which at that time might be 10-15 km away from the village. This would take one or two days.

"We walked 12 km carrying ammunition, grenades, water, enough food for three days, thermal clothing and spare socks. Of course it was tough. Plus, every 30-40 minutes you’d have to hide from drones, sit under cover and wait," one of the soldiers who had been making his way to positions in these conditions for a month told UP.

The day after the soldier spoke with us, he returned to the Kursk front to hold positions near the border. Two days later, he came under artillery fire and sustained a traumatic amputation. His unit continues to carry out its tasks.

Here’s how the phrase "logistics in the Kursk area are difficult" should be interpreted: since at least early to mid-February, the Ukrainian garrison on Russian territory has been unable to transport personnel to positions by vehicle, or to operate equipment, or to swiftly send reinforcements to repel assaults.

All actions have become slow and difficult to execute. Effective defence in such conditions has been impossible.

"If you had six people and two or three of them have been wounded, then who’s supposed to repel the assault? How could we even stay there if we couldn’t bring anyone in properly? The company commander in Sudzha says, ‘I can’t even step outside to take a piss because there are drones everywhere.’ Do you understand?" a soldier from the Air Assault Forces explained to UP.

A signaller from the Air Assault Brigade who spoke with UP noted that in order to reduce the damage caused by Russian FPV drones – especially those operating via fibre-optic cable – the defence forces should have been more effective in eliminating the Russian drone launch points on the flanks, as they did in mid-February, for example, when the Air Force carried out a precision strike that destroyed a platoon strongpoint of Russia’s 60th Motorised Rifle Brigade which had been used for drone launches.

Everyone who spoke to UP, soldiers and officers alike, emphasised the delayed withdrawal of troops from most of Kursk Oblast. They also stressed that in recent weeks the military had been forced to hold the line under unjustifiably harsh conditions.

The most outspoken, yet still broadly supportive, commentators on the Kursk operation were convinced that from a strictly military point of view, the withdrawal from Russian territory should have taken place after the Russian counteroffensive in autumn 2024. However, if that had happened, the defence forces would obviously not have succeeded in wiping out around 20,000 Russians there.

Others insist that the critical moment for withdrawal should have been January 2025, when the Russians began cutting off logistics routes. By February and early March, the Ukrainian group’s defensive effectiveness was already quite low.

Similar assessments were expressed six to twelve months ago from those who took part in another operation – the landing of the Marine Corps on the left bank of Kherson Oblast, particularly in Krynky. The Krynky operation lasted twice as long as the Kursk operation – nearly eleven months – and for most of that time it served a similar purpose: to divert Russia's attention away from Donetsk and Kharkiv oblasts.

Ukraine’s defence forces have often carried off bold and unexpected manoeuvres that catch the Russians off guard, under the command of both Valerii Zaluzhnyi and Oleksandr Syrskyi. But after such manoeuvres, time and again they fail to sustain a prolonged defence due to the poor planning and organisation of combat operations – especially in terms of logistics and countering Russian UAVs. The lack of experienced personnel, and of manpower in general, also works against the defence forces.

Recent strikes on Ukraine’s flanks, infiltration of the rear via the gas pipeline, and the destruction of bridges around Sudzha

Going by the news, you might have assumed that the heaviest and most unexpected blow to the Ukrainian defences in Kursk Oblast was when Russian troops infiltrated the rear of the defence forces’ positions via underground pipes of the Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhhorod gas pipeline. But that is not the case. At the very least, it was not even sudden – but more on that later.

Far more damage was caused to the Ukrainian group by two excruciating strikes by Russian forces on the already significantly compromised flanks.

The first blow fell in February, on the left flank near the villages of Lebedyovka and Sverdlikovo. This offensive proved so successful for the Russians that they later decided to extend it onto Ukrainian territory and launched assaults on the villages of Zhuravka and Novenke and the outskirts of Basivka.

"They went for Zhuravka in January but didn’t manage to advance – we only lost one position there, which we later regained," a serviceman from the 67th Brigade, which is holding this area, told UP. "As for Novenke, that came later, around the end of February, when the 36th Brigade was pushed out of Sverdlikovo. Now Novenke is completely lost and they’re assaulting Basivka. They haven’t managed to gain a foothold in Basivka so far."

The second excruciating and very deep blow was dealt by the Russians in early March, south of Sudzha, between Kurilovka and the village of Guyevo, on the right flank. The Russians broke through the Ukrainian blockade area and advanced 5 km deep into the defence forces’ positions, coming perilously close to the border.

When you look at the map and the locations of these nearly simultaneous strikes, the Russians’ objective becomes clear. They were attempting to cut off the area not only from the air but also by land, from both sides, targeting the Sumy-Yunakivka-Sudzha road, the key tarmacked supply route. They were also aiming to sever the last field roads used to enter and exit Kursk Oblast, which are located south of this main route.

Had the Russians succeeded in reaching these roads, the entire Ukrainian group in Kursk Oblast would have found itself encircled – which was likely their intention. But the encirclement of "several thousand troops" claimed by Donald Trump did not occur.

As of 21 March, there are still points that allow access into and out of Kursk Oblast on foot.

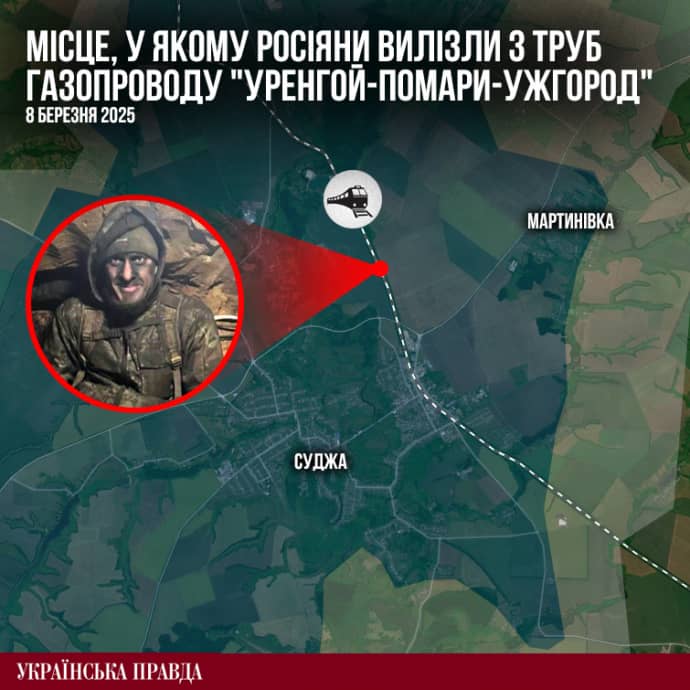

Now back to the Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhhorod gas pipeline.

The defence forces were in fact aware of the Russians’ plans to advance through the pipeline and had prepared to "meet" them. However, at the last minute the focus of both command and personnel shifted – they had to urgently stop the breakthrough of the blocking zone south of Sudzha.

The Russians likely knew about the shortage of personnel within the Ukrainian group and therefore deliberately decided to strike in two locations at once. The defence forces had to make a choice.

"The focus shifted towards Kurilovka, where the breakthrough was happening," one of UP’s sources in Kursk Oblast explained.

"Five days before they came out of that pipe, we already knew about it. The Russians were clearing the exit area with guided aerial bombs. But we were forced to turn around and move to the site of the breakthrough near Sudzha," his comrade added.

The Russians emerged from the 1.5-metre-wide gas pipe at around 05:00-06:00 on 8 March. This happened between Sudzha and Martynovka, where Ukrainian troops were still stationed at the time. Asked why the gas pipeline had not been blown up or blocked in advance, one of the Ukrainian soldiers replied that "it was impossible to do so under the conditions of limited logistics".

That evening, the Air Assault Forces Command posted a video showing missile, artillery and drone strikes on Russian soldiers as they emerged from the gas pipes. However, the exact number of Russians killed or wounded in this way remains unknown. Some of them undoubtedly made it to Sudzha.

This was a physically demanding and perilous task for the Russians. "We heard through intercepted communications that the Russians were saying 'I'd rather go through Ukrainian positions than crawl through that pipe again'," the signaller told UP.

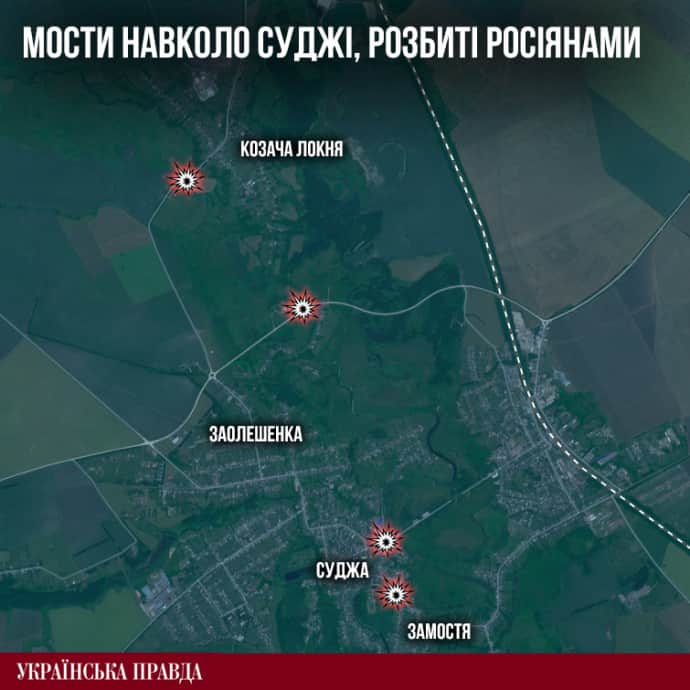

At the same time as they were infiltrating through the gas pipeline in the north of the Ukrainian salient, between Martynovka and Sudzha, the Russians spent several days demolishing bridges around Sudzha itself. In total, they destroyed four bridges over the Loknya and Sudzha rivers – near Kazachya Loknya, between Kazachya Loknya and Zaoleshenka, on the eastern outskirts of Sudzha, and between Sudzha and Zamostye.

An artillery platoon commander named Dmytro, whom UP had spoken with a few days earlier, found himself genuinely grateful for the first time in his life that his howitzer had broken down weeks before. That meant that he had withdrawn the gun from Russian territory in time.

"We had to leave some of our equipment across the river because the Russians were blowing up the bridges," Dmytro told UP. "Anything heavier than 15-17 tonnes couldn’t be moved. We were pretty much unable to recover our damaged equipment from mid-February onwards as there was no way to bring in a tow truck and people refused to go there to do repairs."

The commander of one of the mechanised battalions who agreed to speak with UP said he had kept only minimal equipment in Kursk Oblast due to the precarious situation and had evacuated damaged vehicles at the earliest opportunity.

Another UP source, who is connected to one of the most powerful artillery brigades involved in the Kursk operation, assured us that the brigade had not lost a single artillery unit during the withdrawal.

UP also learned that the defence forces, with the help of one of the most effective UAV units, were forced to destroy some of their own equipment that could not be evacuated. However, the extent of this was nowhere near as great as the Russians claimed.

In the end, due to the Russians striking the flanks, advancing through the gas pipes and demolishing the bridges around Sudzha, the defence forces did come dangerously close to being trapped. This became evident between 6 and 9 March.

"You don’t understand how far the situation had deteriorated... we simply had no other choice but to withdraw [from Kursk Oblast]," one of the battalion commanders whose unit is fighting in Kursk Oblast told UP, sounding both frustrated and resentful.

"The retreat was totally forced," added Dmytro, the artillery platoon commander. "We knew time was running out and we only had days or hours left, yet we spent a week in complete chaos waiting for them to give at least some kind of permission to withdraw. Staying there and continuing to fight was beyond unbearable. In the end, we made the decision to leave on our own…

There was no encirclement, as our command says. But there was no planned withdrawal that would have enabled us to save our equipment either. Many units simply left on foot and marched 15-20 km."

By around 13 March, the defence forces had left Sudzha completely and retreated to the Russia-Ukraine border.

Will the Kursk front become the Sumy front?

Will Russia now shift combat operations to Sumy Oblast?

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has said that Russia is already amassing forces in the east to attack Sumy Oblast.

During his recent visit to Kursk Oblast, Vladimir Putin assigned three tasks to Russia’s Chief of General Staff, Valery Gerasimov: to fully "liberate" Kursk Oblast; to restore troop positions along the state border; and to "especially consider in the future" the creation of a "security zone" along the border.

This last "task" could be interpreted as a potential Russian attempt to seize 2-5-7 km of Ukrainian territory along the border. Russian milbloggers, observing the capture of the Ukrainian village of Novenke, have even described the area as a "ready-made foothold" for an advance into Sumy Oblast.

However, all the sources interviewed by UP, including troops from the 67th Brigade stationed on the Zhuravka-Basivka front, insist that Russia’s primary objective was to advance towards Sumy Oblast solely to gain proximity to the Sumy-Yunakivka-Sudzha road.

"They just needed to push us out of Kursk Oblast and to do that, they had to cut off the road – hence their push into Novenke," a paratrooper explained to UP.

"If the Russians do decide to attack Sumy Oblast, it certainly won’t be here in Basivka, where we’re waiting for them and where they know we’re waiting for them," a soldier from the 67th Brigade added.

While working between three and ten kilometres from the border and near Sumy itself, UP observed defence lines featuring anti-tank obstacles known as dragon's teeth and networks of trenches and bunkers in several locations.

Some of these positions, such as dugouts for command posts and camouflaged bunkers for vehicles, are currently being constructed by Ukrainian units. Neither we nor our sources can fully assess the suitability of the locations chosen for the fortifications or evaluate their quality.

Nevertheless, in any discussion of whether "the Kursk front will now become the Sumy front", it is important to note that Ukraine’s defence forces have not entirely withdrawn from Kursk Oblast. Ukrainian units remain on Russian territory at a depth of 3-5 km, holding positions in villages such as Gogolevka and Guyevo.

It is likely that the defence forces aim to secure high ground on the Russian side of the border for better reconnaissance and more effective drone operations, and to use Russian positions as defence strongholds for Sumy Oblast.

As one of UP’s sources on this front summed it up: "Our task now is to stabilise the situation. It’s not completely stable yet, but we are close."

Olha Kyrylenko for Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Anna Kybukevych, Anastasiia Yankina and Tetiana Buchkovska

Editing: Teresa Pearce