"It's like being freed from a horrible stench": the young people starting a new life after leaving Russian-occupied areas

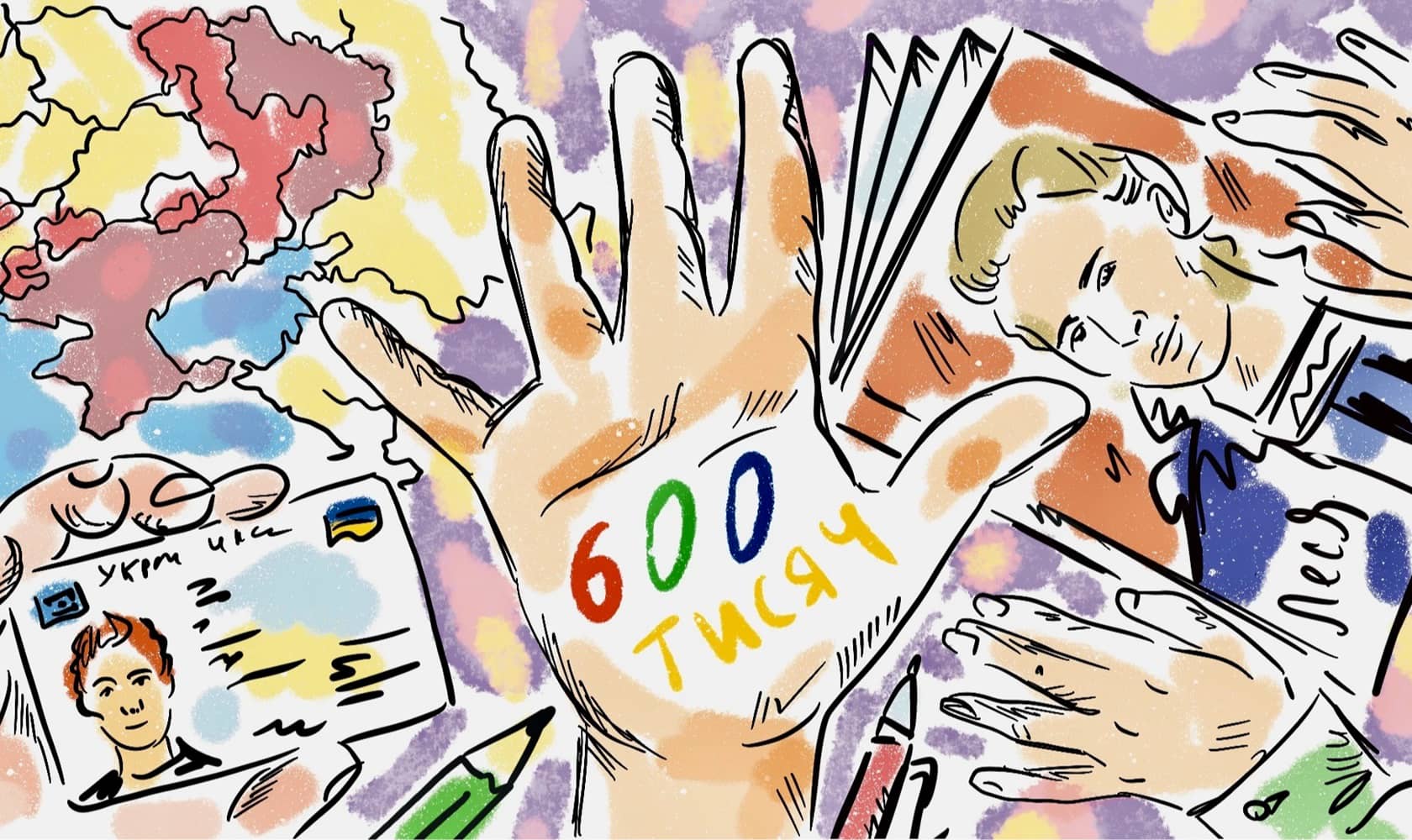

Six hundred thousand. That’s the approximate number of school-age children who remain in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine. One in twelve students forced to study the Russian curriculum still manage to stay within the Ukrainian education system.

Despite the dangers they and their families face, these children continue to read the works of great Ukrainian writers like Taras Shevchenko and Lesia Ukrainka, holding onto their dream of living in Ukraine and pursuing higher education in Ukrainian-controlled territory. This is their conscious choice.

But 600,000 is not the limit. There could be many more such children if the Ukrainian government made it easier for them to cross the border and access education.

These stories of young people who have chosen Ukraine and believe in its future are proof of this. These accounts have been collected by the Donbas SOS human rights organisations and the ZMINA Human Rights Centre.

Biankpin Akassi Zhan-Evelin

"When you wake up and see the [Russian] tricolour outside your window, you want to run away – anywhere, just so you can’t see it"

"I don’t know exactly what made me leave Donetsk for Ukrainian-controlled territory. I was in first grade when the ‘Russian world’ came here. As a child, I was fascinated by ‘Great Russian’ culture, but there was this moment when I felt completely alien to it.

Before 2014, our school was Ukrainian-speaking, but after that, Ukrainian was only taught once every two weeks. Our class did not accept the teacher or the subject itself. My classmates protested against the lessons and disrupted classes.

I remember being surprised that the library wouldn’t lend you books by Ukrainian authors like Franko or Shevchenko. They were there on the shelves, but no one could take them out. It was only thanks to the internet and music that I felt a connection to Ukrainian culture. I listened to Russian-language songs by Vremya i Steklo and Potap. I knew who Skryabin and Okean Elzy were.

But Ukrainian music – even if it was in Russian – was banned in Donetsk as soon as the full-scale invasion started. The only connection to Ukraine was through YouTube and TikTok.

In 2022, I was 16.

I’d been drawn to Western culture since I was a child. I often dreamed of moving to Canada and living happily there. I had older friends, boys, in Donetsk, but they were all called up. Many of them are no longer alive...

I don’t know how to explain what life under occupation feels like. When you wake up and see the [Russian] tricolour outside your window, you want to run away – anywhere, just so you can’t see it any more…

I decided to leave, even though I wasn’t 18 yet. I spent a long time getting the necessary documents together. Finally I set off on my journey to Ukrainian-controlled territory through Russia, Belarus and Poland. It was around the time when the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant was blown up… The journey took 10 days.

I had no idea what lay ahead. My entire life was packed into two suitcases. I had to place all my trust in volunteers – people I’d never met before. I had to watch my words and remember that the word ‘war’ did not exist, and neither did the word ‘volunteer’.

I was travelling with a girl from Luhansk. The situation at the Belarus-Poland border was very difficult. The border guards did not want to let us through. I got so nervous that my temperature went up to almost 40°C (104°F). Suddenly they told us that it was some kind of holiday for the border guards, and the Belarusians decided to let everyone who had been held back until then go through.

As I crossed the border, I downloaded Okean Elzy’s song Na linii vohniu (In the Line of Fire) and listened to it on my headphones, and I cried. I’d been too afraid to download it earlier because if the Russians or Belarusians had seen it on my phone, they would probably have detained me.

The girl from Luhansk who had travelled with me was heading to an EU country, while I was on my way back to Ukraine. I faced hours of interrogations at the Poland-Ukraine border. I was exhausted.

If there is any way to make this journey easier for young Ukrainians who want to leave the occupied territories, it would be awesome.

I arrived in Kyiv in August, but I didn’t receive my internal passport until January. I lived without a passport for half a year – I couldn't rent an apartment or even get a student card. I enrolled in university surprisingly quickly. I hadn’t expected to become a first-year student so easily. But I got no assistance from the state. And for students like me, that support is vital. We need to attract people here and take care of those who have come here. Right now, there aren’t many of us, sadly."

Mariia Krasnenko, a lawyer and expert at a coalition of organisations focused on protecting the rights of people affected by the armed aggression against Ukraine:

Children who decide to leave for Ukrainian-controlled territory do indeed face numerous obstacles: problems obtaining identity documents (especially for those coming from areas that were occupied before the full-scale invasion), challenges crossing administrative borders, logistical difficulties when travelling through Ukraine, and not having enough money to make the journey.

Often they are under 16, meaning they require parental involvement. However, some parents cannot leave the temporarily occupied territories for objective reasons or hold different views from their child. In addition, support remains insufficient even after they manage to leave.

Although they can access free housing in student accommodation and obtain student grants (academic scholarships or bursaries), UAH 1,000 (about US$24) per month is totally inadequate to cover living costs. These children are forced to find work so that they can afford to buy basic necessities like food, clothing and essential technology.

That’s why consolidated efforts are needed from government agencies, local authorities and non-governmental organisations. Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry and the State Migration Service, in particular, should assist with border crossings by providing advice, expediting document processing, and issuing certificates for their return to Ukraine. The latter is especially relevant given that there are reports of Belarusian border guards at the Mokrany checkpoint refusing to let people through without proof of Ukrainian citizenship or a certificate of return.

It is also essential to establish a support system to help these students adapt to their new educational environment and to life as internally displaced persons – providing psychological, social and financial assistance. In addition to the Ministry of Education and Science, the Ministry of Social Policy should also play a crucial role, since it is responsible for dealing with issues concerning both IDPs and residents of the temporarily occupied territories.

Vasyl

Enrolled in medical school for the second time to complete six more years of study, obtain a Ukrainian degree, and work in Ukrainian-controlled territory

Vasyl (name changed for security reasons) is now 23. He had just finished school when his hometown of Donetsk was occupied in 2014. At the time he was living in the moment, enjoying being young, and he decided to go to medical school, and then continue his education at Donetsk Medical University, purely because his parents were in the medical profession. Vasyl completed his higher education while living under occupation.

Vasyl is unable to pinpoint exactly what made him consider leaving Donetsk. Most likely it was his chosen specialty – paediatrics. At some point, he started paying closer attention to news reports and analysing events. He realised that the number of indiscriminate shelling attacks by Russian forces was significantly higher than those by Ukrainian forces, and that far more children were affected by such attacks in Ukrainian-controlled territory. And he wanted to help children.

By then, Vasyl had a degree issued by the Russian authorities. But he had no desire to stay in Donetsk. His parents were firmly opposed to going with him. They did not want to leave their home, and their age made long and exhausting journeys difficult.

Fortunately, Vasyl had kept his Ukrainian passport. He had travelled to Ukrainian-controlled territory to obtain it before Russia’s full-scale invasion. Thanks to this passport, he was able to reach an EU country. He could have stayed there, received social benefits, even had his degree recognised and worked as a healthcare professional. But that thought never even crossed his mind. He returned to Ukraine to fulfil his goal of helping children affected by Russian aggression.

Vasyl was so determined that even the Ukrainian government’s refusal to recognise his Russian-issued degree did not discourage him. He enrolled at medical school again, committing to another six years of study to finally obtain a Ukrainian degree and work in his chosen profession.

Vasyl admits, however, that he had expected the process to be much easier than it turned out to be. He had hoped that his knowledge would be validated without him having to do all that studying again, especially since this was permitted by the Law on Education as of November 2023. However, it turned out that the procedure for this recognition had yet to be approved.

He was also unable to have his medical skills recognised so that he could at least work as a junior medical staff member. So his only option was to become a student again and start his journey anew.

Vasyl does not regret his choice, even though it means spending an additional six years of his life in education. He is convinced that this path is better than staying under occupation and living a life that is not truly his own.

He currently works as an orderly in a Kyiv hospital to support himself. However, he admits that life is quite difficult for displaced persons, especially for students.

Lawyer Mariia Krasnenko comments:

The demand for education and employment on the basis of skills acquired in the temporarily occupied territories remains high.

On 21 November 2023, the Ukrainian Parliament amended the Law on Education to make it possible to recognise academic achievements obtained in occupied areas. The government is supposed to establish the procedure for such recognition, including conditions, exceptions, and other details.

However, as of early 2025, deadlines have been and gone, and this has not been done. This failure for over a year to adopt procedures that were meant to make it easier for children and young people to leave the occupied territories is undermining Ukraine’s reintegration policy, as NGOs have noted in an appeal to the government.

Specific procedures also need to be put in place at each educational institution, and staff need training to ensure the process is as smooth as possible and complies with all requirements. Assessment methods should include clear guidelines and a defined scope of requirements.

Once their academic achievements have been recognised, individuals will be able to continue their education with a reduced period of study. However, recognition will not be possible for all fields.

Svitlana

"In Chernivtsi, I will be able to sleep peacefully"

Svitlana (name changed for security reasons) was still a child when she told her parents she wanted to leave Russian-occupied territory. Her dream was to go to the "Harry Potter school" – Chernivtsi National University in Ukraine’s west. With its towers and vaulted arches, it’s known as "Ukraine’s Hogwarts".

Svitlana had been fascinated by it ever since she saw it as a little girl. She used to dream about it at night, and she never doubted for a moment that she had to study there.

Svitlana has vivid memories of a trip she made to Ukraine’s west when she was a first-grader. Her hometown was already occupied by then, but there was still a connection with free Ukraine, so her mother decided to take her to the Ukrainian Carpathians, where life was calmer, for the summer.

After returning from Chernivtsi, Svitlana continued studying at her school, following the Russian curriculum. However, her parents found a way to enrol her in online lessons from a Ukrainian school. In this way, she studied under both systems.

Ukrainian songs by popular bands helped her master the language. She would listen to them on her way home from school. Svitlana read in Ukrainian – her parents managed to find books for her. Despite the aggressive Russian propaganda, she decided she would study Romance and Germanic philology at Ukraine’s Hogwarts. The level of foreign language teaching at schools in her hometown was low, so she had to seek out private tutors.

They did this discreetly, as it was Svitlana’s secret. She could not tell anyone [except her parents – ed.] what she truly aspired to and how hard she was working to achieve her goal.

Now Svitlana speaks fluent Ukrainian. She has excellent knowledge of the topics in Ukrainian Studies – an achievement largely due to her parents – and her foreign language skills were good enough to pursue her dream. And although she was still a minor when she finished school, her parents decided to take her out of the occupied territory so that she could apply to the university she had always dreamed of.

Svitlana recalls telling her parents: "I’ll be able to sleep peacefully in Chernivtsi." Her family agreed – it would indeed be much safer for her there than in Ukraine’s east.

Until August 2024, there was still an operational crossing point on the border between Russia’s Belgorod Oblast and Ukraine’s Sumy Oblast (Kolotilovka – Pokrovka). Despite the constant escalation and fighting in the area, Svitlana's family decided to risk it.

Svitlana’s mother travelled with her. They went via Russia. They had to conceal the real purpose of their trip, so they said they were going to visit relatives. On the way they were frequently stopped by security forces, who would check their phones and question them.

When the two women were right at the border, the Russians took issue with the amount of luggage they were carrying – the girl had significantly more than her mother, which seemed suspicious to them. At that moment, Svitlana's heart sank. It looked as if they wouldn’t be allowed to leave, and she would never reach the road sign with "Pokrovka" written in black letters on white.

Fortunately, they were allowed to cross the border. Svitlana obtained a Ukrainian passport and the other documents she needed to be admitted to the university. Her dream had come true.

Svitlana had to stay in Chernivtsi by herself: her mother returned to their family in the temporarily occupied territories. Svitlana realises that she cannot return home until her hometown is liberated. She is still alone in a new city, with no family members and fairly limited financial resources. She says it isn't easy for her, as her studies cost money.

Violetta Artemchuk, Chief Coordinator of Donbas SOS, comments:

If you have decided to apply to a Ukrainian university, the first thing we recommend is to choose an educational institution right away. This is an important step, because going forward, the applicant will need to contact representatives of the educational centres at these universities to ask questions and register for exams.

Once you have chosen a university, you need to contact the Donbas/Crimea-Ukraine Centre (essentially an admissions committee for applicants from the occupied territories). You can also get in touch with human rights organisations, including ours: we can provide contact details and guidance.

We want to point out that the process of leaving the occupied territories has become significantly more difficult in 2025. The humanitarian corridor between Ukraine and the Republic of Belarus, which was formerly used by citizens without Ukrainian passports (and most university applicants will not have obtained Ukrainian passports yet), is practically non-functional.

Travelling through European countries is also difficult. However, there is a procedure for remote exams, which means applicants can gain a place at a university without leaving the occupied territories.

If an applicant does not have Ukrainian documents, it is recommended to apply for remote admission. If an applicant has nevertheless moved to Ukrainian-controlled territory and plans to apply offline, we also recommend that they keep in touch with the Donbas/Crimea-Ukraine educational centre at their chosen university and seek advice from NGOs in the event of any complications or misunderstandings in the admissions process.

Ilyas Sheikhislyamov

"It’s like being in a smoke-filled room, and when you step outside into the fresh air, you feel relieved, as if freed from the stench. That’s what leaving the occupation feels like."

"My father called me from a Russian detention centre and said he was proud of me because I was studying to become a lawyer in Kyiv. It was very hard not to cry after hearing those words.

My family has never supported the occupation of Crimea. After finishing school on the peninsula, I went to Türkiye to study theology. We are a very religious family, and I thought it was the right thing to devote myself to God. However, after my father was detained by Russian security forces in early 2024, I decided that I had to become a lawyer to help my fellow Crimean Tatars.

After the occupation of Crimea in 2014, I would return home from time to time, but I couldn’t stay long. I wanted to leave at all costs.

Life under occupation is hard to describe. It’s like being in a smoke-filled room, and when you step outside into the fresh air, you feel relieved, as if freed from the stench. That’s what moving to Ukrainian-controlled territory is like.

I came back from Türkiye and lived in Odesa for a while to be as close as possible to Crimea and my parents. But then my father was arrested… After that, I started thinking about how I could help him and other political prisoners. I had always wanted to go to Taurida National University. Even when I was still living in Crimea, I often thought about it. And it was the only university that had relocated from Crimea to free Ukrainian territory, so I chose it.

But I left school a long time ago. During my last school years, I studied under the occupation authorities. I had to redo my documents and get a Ukrainian-style certificate.

I enrolled in the university through the Crimea-Ukraine educational centre. The staff there are wonderful and very open in their communication. But there were a lot of challenges, especially communication problems with the applicants. For example, I found out about an exam I had to take 15 minutes before it started online. One day I had four exams – two to confirm my certificate and two entrance exams. When I got up from my desk after the fourth exam of the day, I thought I had no strength left to move at all.

And yet by some miracle I got into Taurida National University. Not only that, my scores were among the highest in the class.

I am happy that I can study. But I don’t have enough support from the state. My scholarship is UAH 1,180 (US$28) per month. The whole scholarship goes on utility bills, and I don't have enough money for food.

Another problem is money transfers from occupied Crimea. Even if relatives wanted to help out and send money, it’s not possible. So I have to rely solely on my own strength, and hope for help from the state and for the liberation of Crimea."

Aliona Luniova, advocacy manager at the ZMINA Human Rights Centre, explained what the state should do to support young people from the temporarily occupied territories:

The state runs separate programmes for young people from the occupied territories through educational programmes. For example, there are the Crimea-Ukraine and Donbas-Ukraine educational centres, which help them with university admissions. Also, thanks to a legislative initiative, validation of education obtained in occupation has been introduced (unfortunately these procedures are not yet in place).

However, there are other tasks that are very important for the state to carry out, namely the introduction of a comprehensive system of support for young people from the occupied territories. There should be comprehensive support for young people at every stage – from thinking about leaving, to getting settled in Ukrainian-controlled territory.

It’s especially important to provide support with obtaining a Ukrainian passport, as many young people do not have one and never received one because they came of age during the occupation.

As well as help with documents, there are also issues to be addressed with regard to adaptation and learning about the topics on the Ukrainian Studies curriculum.

It is also crucial to help young people from the occupied territories into employment. Such comprehensive support should be put in place as soon as possible and become an integral part of Ukraine’s policy on young people.

This piece is funded by UK International Development from the Government of the United Kingdom. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UK Government.

Hanna Horozhenko

Translation: Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Anna Kybukevych, Tetiana Buchkovska

Editing: Teresa Pearce