More trouble ahead: as Russia enters 2025, how is the economy doing?

A thousand days of Ukrainian resistance during the full-scale war and Western sanctions have left their mark on Russia's economy: military spending is skyrocketing, and sanctions are imposing ever greater restrictions on international trade.

A crack in the Russian economy

In 2024, the Kremlin's spending on the war with Ukraine will reach a record RUB 16.3 trillion (around US$147.5 billion), more than 8% of its GDP and 41% of the total central budget. Driven by an escalation in the intensity of fighting, Russia’s military spending has risen by 59% this year compared to 2023.

Relying on the principles of "military Keynesianism", Russian leaders expected this public spending to deliver macroeconomic stability and continuous economic growth. But due to the country's high dependence on imports and the diversion of resources from the civilian economy to the war effort, the bet didn’t pay off.

One important detail in the organisation of this war is that the Kremlin's military recruitment model involves making large payments to its soldiers. This is a new way of fighting wars in Russia, as historically their troops cost almost nothing.

Each contract soldier is paid RUB 4-4.5 million (around US$40,000) per year, and the same amount is paid out in the event of serious injury or death at the front.

Money is what motivates Russians to fight. These vast sums, which reach RUB 3.5 trillion (about US$31.7 billion) a year, are funded by the state budget. As a result, a significant portion of military spending ends up being paid to those involved in the war.

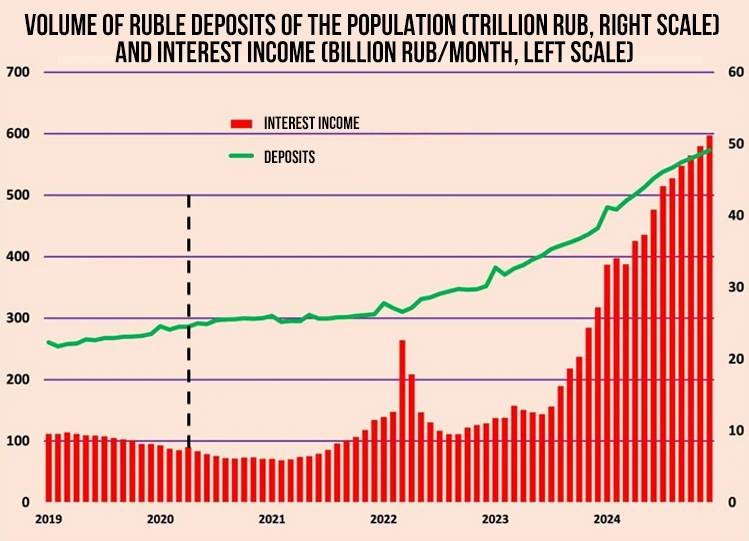

From there, the funds "migrate" to commercial bank deposits. There are two reasons for this: the high deposit rates, 22-23% per annum, the key rate being 21%; and the lack of a sufficient supply of goods and services for this money to be spent on or invested in. By the end of 2024, the Russian population had built up over RUB 52 trillion (about US$470.6 billion) in deposits.

This "pile" of money makes it look as if Russians are growing wealthier. However, there are not enough commodities for the Russians to spend that money on, and no added value has been created in the form of useful goods and services.

War means vast unproductive expenditure. A tank or a gun produced has no consumer value for an individual, including the one who uses it in the war. The civilian economy that has been sacrificed is unable to provide a supply of useful goods that would balance and tie up demand.

Since June 2024, Russia has officially reported a cessation of growth in industrial production. There are a number of reasons for this. The first is the labour shortage due to mobilisation, migration in 2022, and the deportation of Central Asians following racially motivated persecution this summer.

The second reason is the high cost of the loans used by companies for their operating activities. Currently, this cost exceeds 25% and takes up almost all of many companies' gross profit.

Then there are the consequences of Western companies pulling out from Russia, including the suspension of their production lines. The timer on this ticking time bomb is already starting to count down.

For there to be any change in the current state of affairs, economic resources must be directed towards developing civilian production. However, that would necessitate a dramatic reduction in military funding, i.e. ending or freezing the war.

The impact of the factors listed above has caused the Russian economy to develop a significant imbalance between supply and demand, or, in other words, a lack of useful goods to buy with the cash available. The inflation that is rampant in the Russian Federation is a direct consequence of this distortion.

Unless the war ends and/or sanctions are lifted, there will be two outcomes: stagflation (when production falls while prices rise) or galloping inflation followed by hyperinflation, which will destroy the production process.

This is the trap the Russian economy has been driven into by its leader's military adventure.

Attempts to head off the looming catastrophe

The Russian authorities have been forced to admit that inflation in November and December was 0.4-0.5% weekly or 1.5-2% monthly. Given the possible distortion of statistics, it could be even higher, reaching 3% per month.

Russia’s Centre for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting has announced the onset of stagflation. On 20 December, the Board of Directors of the Russian Central Bank decided to keep the key interest rate at 21%. This decision was made under pressure from the industrial lobby, including representatives of Russia's military industries, where the high cost of credit is draining resources.

Read more about this topic: What's going on with the Russian economy?

The Russian Central Bank's decision de facto shows that the regulator has exhausted its inflation-fighting tools. Raising the key policy rate to 22% or 23% would have no effect, and the governor, Elvira Nabiullina, is well aware of this and of her own powerlessness.

After such a decision, we can expect inflation to spiral even more. It isn’t just the civilian economy that’s being sacrificed to the war, but Russia's financial system as well.

The decision is clearly intended to preserve the production of war-related goods and the profits of the oligarchs involved. But the financial system has its own laws and does not tolerate administrative violence, and it will soon make this very clear.

How will the war be funded now?

It is crucial to understand how military expenditure will be funded in this situation. Russia's war will be financed from three main sources: the National Wealth Fund, gross revenues of oil and gas companies, and the direct issuance of money by the central bank.

Currently, these sources are significantly weakened. Only about US$47 billion is left of the US$150 billion that was in the National Wealth Fund at the start of the large-scale war, primarily in the form of sanctioned gold and Chinese yuan. The fund shrank by approximately US$50 billion each year in 2022-2023. Notably, expenditure from the fund is particularly high at the end of the year, when budgetary settlements for economic and social obligations must be made.

The amount due this year is particularly high, suggesting that the remaining funds will not be sufficient to cover the budget deficit by the end of 2024.

This is evidenced by the covert issuance of money by Russia's Central Bank. As part of this, commercial banks received short-term loans in December to purchase government bonds. The amount issued was RUB 2 trillion (approximately US$18.1 billion). Consequently, the Fund can no longer fulfil its role as a financial cushion for the government during a critical period.

The profits of oil and gas companies have been siphoned off since late 2023. The downside of these expropriations is the deteriorating financial health and capitalisation of these companies. This is evident from the dramatic decline in the value of Gazprom's shares.

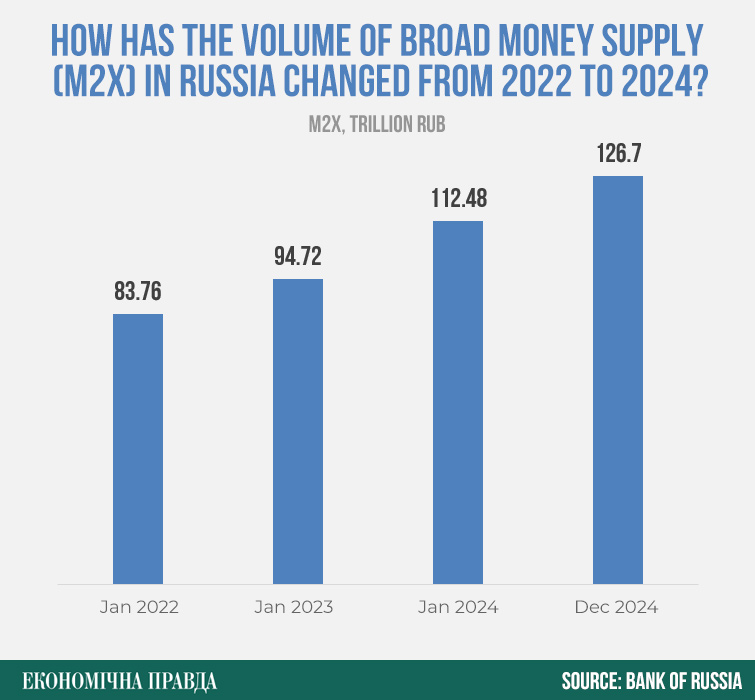

Finally, printing money remains an instrument the Kremlin eagerly uses to finance the war.

The 1.5-fold increase in the money supply over three years has already played a significant role in fuelling inflation and causing distortions in the economy. The issuance mentioned above has added another RUB 2 trillion (US$18.1 billion) to the money supply. Most of these funds will reach the consumer market in January and February 2025.

A combination of factors will work against Russia in 2025: the drying up of the National Wealth Fund and the anticipated drop in oil prices – oil is still the primary fuel for Russia's military funding. Key agencies are forecasting Brent crude prices at US$65-70 per barrel, compared to US$80 this year.

Printing money remains an option, but it is risky in an overheated economy with inflation high and rising. However, Russia is unlikely to get by without doing this, which means significant financial destabilisation for the aggressor should be expected in 2025.

In summary

Since the failure of the lightning offensive, the Kremlin-imposed war has turned into a war of resource depletion. It diverts funds from other sectors, especially social programmes. Prices are rising at a rate of 2% per month, while production is at best stagnant.

The Russian population feels the negative impact of the war through a loss of purchasing power and awareness of the losses in Ukraine. This war is more sensitive to the state of the economy than Russia's previous conflicts were.

The Russians fighting in this war are doing it for money. If that money is devalued by inflation, they will have far less motivation to fight and to die.

The Kremlin has no way of stabilising inflation and boosting civilian production other than cutting military spending and having the sanctions lifted. The latter would be a genuine lifeline for the Russian economy.

In 2025, Russia's economy will be operating with depleted financial reserves in the National Wealth Fund and lower oil prices. Printing money remains the most accessible source of funding for the government, but it is increasingly risky in an economy overheated by inflation.

It is difficult to predict the exact timing of a deep crisis, but under such circumstances, galloping inflation of 3-4% per month can be expected in the first or second quarters, which would signify the onset of a crisis. By mid-year, a sharp increase in crisis sentiment among the populace is highly likely.

Unlike Russia’s, Ukraine’s economy is financially secured for 2025 owing to the support from its partners, so claims that Russia will be able to fund a war of attrition for longer than Ukraine can with its partners’ support seem like propaganda.

The Kremlin is already under severe economic pressure as a result of the aforementioned economic distortions. The economy is becoming a factor that could force Putin to pause this phase of the war and seek ways to ease sanctions.

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska and Anastasiia Yankina

Editing: Gabriel Neder and Teresa Pearce