Occupied education. How Russia distorts the minds of Ukrainian children in Kherson

Today, millions of Ukrainian children are starting another school year, either in Ukraine or abroad in the West. However, some remain under occupation, as more than 500 Ukrainian schools are still under Russian control.

Parents and teachers who resist the imposed education risk their own freedom and that of their students. Meanwhile, children are increasingly fearful of returning to Ukraine, labeling themselves as traitors.

How Russia is implementing its plans to enslave new generations through distorted education is explored in a study by The Reckoning Project, specially for Ukrayinska Pravda.

In October 2020, the Kherson City Court released Tetiana Kuzmich, head of the "Rusych Russian National Community", on bail of half a million hryvnias. This NGO operated in the Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa regions and Kuzmich was suspected of spying for Russia.

At the same time, Kuzmich served as a senior lecturer at the Kherson Academy of Continuing Education, giving her access to the teaching staff of local schools.

The Rusych community claimed its purpose was to "preserve and disseminate among young people the traditions of the Russian people." Similar organizations in Crimea and eastern Ukraine had previously become hubs for collaborators engaged in spying and bribing local elites. In the two years leading up to the invasion, over a hundred such organizations were active in Ukraine, but Kuzmich’s case stood out as particularly significant.

"At the time, we had her in our hands, and during the pre-trial investigation, we collected more than enough evidence to find her guilty and observed all the rules. Obviously, Russia simply made a deal with its rats among us, and she was released," a law enforcement source who worked on the criminal case against Kuzmich told the authors of the material.

Tetiana Kuzmich waited for Russia’s full-scale invasion and became one of the key figures in the takeover of education in the Kherson region, assuming the role of head of the occupation department of education and science for the region. In mid-summer 2022, in Kherson, the spy Kuzmich announced that schools in the region would operate according to Russian standards and that children would receive Russian certificates.

Today, Kuzmich has risen to the position of deputy for refugees affairs under the so-called governor of the Kherson region, Volodymyr Saldo. She also claims her mission is to "restore Russianness to those Ukrainians who remain on the other side today, which she describes as an aspect of the so-called denazification of Ukraine".

Recruitment of teachers

The occupiers conducted an inventory not only of the property but also of the staff at the schools. Starting in mid-summer 2022, most of the region’s institutions held working meetings. This was possible where principals cooperated with the occupation authorities or where the Russians could easily appoint someone to the position of head of the institution.

"Our principal, Oksana Kryvenkova, sent us an invitation to the meeting via Viber. My colleague, computer science teacher Natalia Vaskovska, and I decided to attend. We suspected what was coming. Kryvenkova, speaking in Russian, said that she had been appointed by Saldo and that the school would operate offline according to the Russian curriculum," says Viktoria Kovaleva, an English teacher at Mykilskyi Lyceum.

The Russians aimed to make this school in the Darivka community of Kherson Oblast an exemplary one. This was facilitated by the then-principal and a group of local pro-Russian activists who appealed to the occupation administration to open the school.

"The expressions on our colleagues’ faces immediately revealed who was ready to cooperate. They had succumbed to propaganda," Kovaleva adds. "Natalia and I listened to all of this, took our things, and left. I haven’t been back to our school since."

According to the teachers, about ten of their colleagues at Mykilske School cooperated with the occupation administration.

"I wanted to demonstrate that we have not given up."

In all schools in the occupied territories of the Kherson region, teachers were promised a bright future with Russia. They were offered retraining in Crimea, encouraged to resign from Ukrainian schools, and given opportunities to work in new institutions established by the Russians based on Ukrainian schools. In Kherson alone, more than 25 such "state institutions of the Russian Federation" were created.

Natalia Zhurzhenko, head of the Kherson City Council’s education department, explains that the occupiers spent the entire summer taking over school buildings but then realized they didn’t need them all:

"They couldn’t open all the schools because there weren’t enough people willing to study, so they created a separate list of institutions. In Kherson, this list includes our best schools."

One of these was Preparatory High School No. 6, located in the very center of the city. The occupiers conducted repairs to prepare for the new school year and invited the school’s teachers to return to work. They began recruiting the school’s management in hopes that others would follow. However, in August 2022, an incident occurred at the school that greatly alarmed the occupying officials.

After another refusal to accept an offer of cooperation, which ended in threats to her family, Iryna Radetska, the deputy principal of Preparatory High School No. 6, took a desperate step. Disguised as a mother seeking to enroll her child, she visited her former school and requested a personal meeting with the new "principal" appointed by the Russians.

Upon entering the office, Iryna told the self-styled director that she had a grenade in her bag and intended to detonate it right there. A few days after this dramatic encounter, the Russian military visited her home. She was forcibly taken to a temporary detention center on Teploenerhetykiv Street, where the occupiers had set up a torture chamber for residents of Kherson who resisted their rule.

Radetska was held there for just over a week, enduring torture with electricity, water, and beatings with sticks and kicks. Following her bold action, the Russians forced her to record a video apology before allowing her to return home.

"It was a conscious decision. Perhaps I didn’t fully understand the consequences, but I just love my Ukraine. I wanted to show that we are not afraid of anyone, that we have not surrendered. I wanted them to know that they are here temporarily," says Radetska.

In addition to seizing school buildings, the Russians took control of the entire educational infrastructure: departments, the Institute of Postgraduate Education for Teachers—where meetings with collaborating teachers were held—and they opened an office of the Russian Ministry of Education in the building of "Pryvatbank."

This office was chaired by Mikhail Rodikov, the so-called Minister of Education of Kherson Oblast. In August, he sent a letter to Alexander Bugayev, Deputy Minister of Education of the Russian Federation, detailing the number and titles of textbooks for the Kherson region, which were to be supplied under subsidies from the "Russian World" Foundation. On the eve of September 1, Rodikov stated: "If there are not enough teachers, we will request them from Russia."

"They recruited anyone willing to take on a leadership role. For example, the School No.27 was headed by a former law enforcement officer," says Natalia Zhurzhenko.

In another city school, an English teacher was offered by a collaborating principal to join the occupation teaching staff with the rationale, "What difference does it make whether you teach English according to the Russian or Ukrainian curriculum?"

"Now this principal has fled to Russia and is working in their education system, while here she is suspected of treason," said a teacher at a Kherson school, who requested to remain anonymous for security reasons.

The preparations for the first occupation school year in the Kherson region followed the same pattern everywhere: establishing a controlled administration, persuading parents to send their children to school through loyal teachers, offering one-time financial assistance of 10,000 rubles, and importing Russian textbooks and curricula.

"...Portraits of Putin and tons of Russian textbooks"

Russian State Duma deputy Igor Kastiukevych faithfully performed his duties as a curator during a Kremlin business trip to the Kherson region. From the first days of the occupation, he was in charge of "the humanitarian policy of ‘United Russia’." Kastiukevych was involved in war crimes, including the illegal deportation and forced displacement of Ukrainian children, for which he was suspected by the SBU.

At the same time, Kastiukevych actively promoted hatred toward everything Ukrainian. In March 2022, he posted a video promising to send Ukrainian textbooks from a Kherson school to Moscow for an examination of "Nazi ideas."

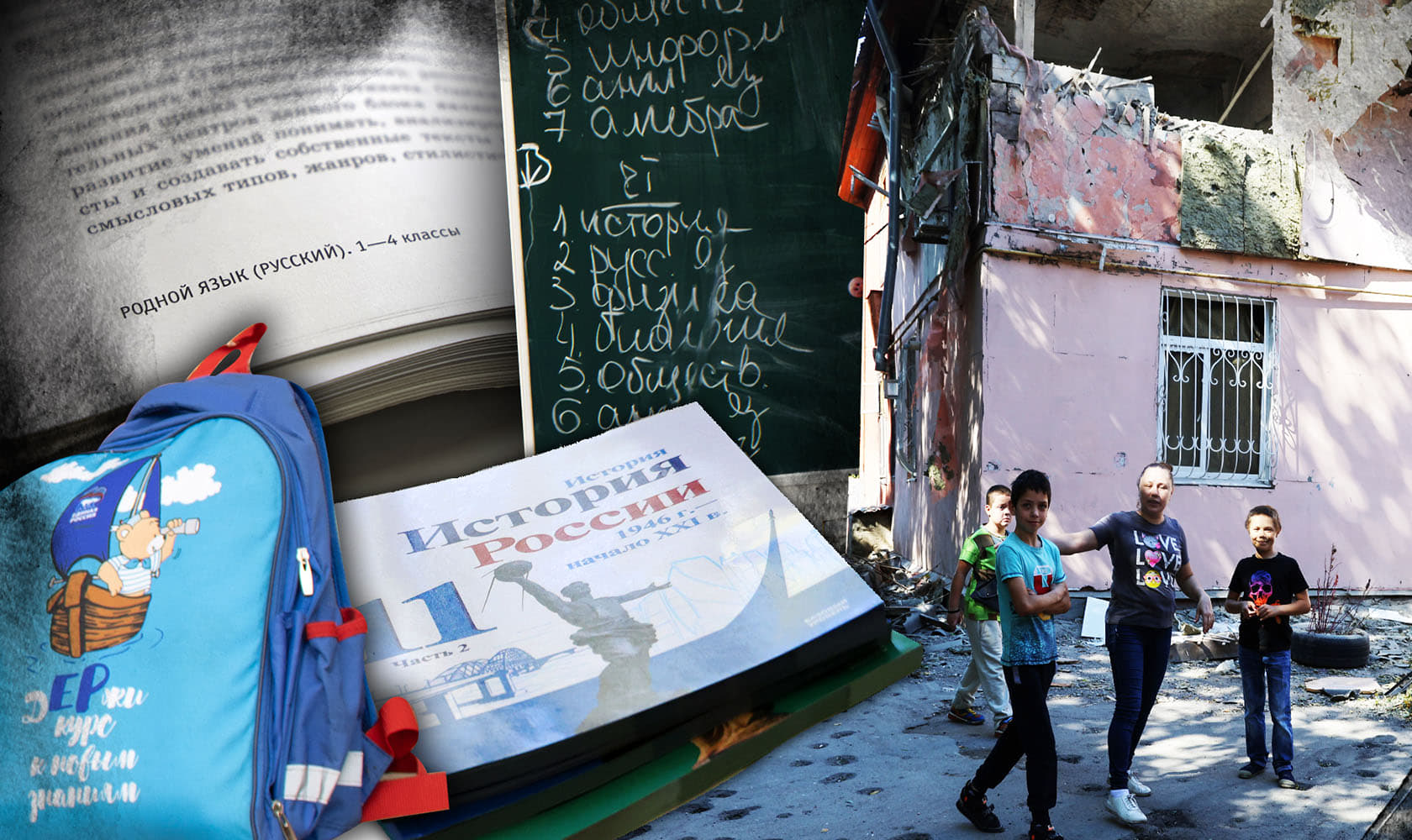

Meanwhile, the Russians printed and brought more than 600,000 copies of their textbooks to the Kherson region, including 257 different types.

"Russia is the world’s largest power, actively advocating peace and stability on the planet... It pursues a balanced, peace-loving foreign policy, taking into account its geopolitical interests," reads the 11th-grade History of Russia textbook.

Serhiy Horbachov, who was the Education Ombudsman of Ukraine at the time, responded to our inquiry by stating that children in the Kherson region were effectively banned from studying Ukrainian subjects.

"All Ukrainian textbooks were confiscated and sometimes destroyed, and Ukrainian historical and fiction books were also removed from libraries. Instead, new, propagandistic subjects such as ‘History of the Fatherland’ were introduced in schools," Horbachov commented.

"We still have this crap in our schools — tricolors, portraits of Putin, and tons of textbooks," says Stanislav Kovalenko, Coordinator of the VDOMA Center.

After the de-occupation of Kherson, he toured the city’s educational institutions and discovered that while the Russians took documents and equipment with them, they left behind large quantities of educational literature. These textbooks are now being used as evidence in criminal proceedings related to the imposition of Russian educational standards in the occupied areas.

Stanislav shows us a Life Safety Fundamentals textbook published in Moscow in 2022. The project researchers found similar copies in most schools on the right bank.

The book is filled with terms such as "national security strategy of the Russian Federation," "national interests of the Russian Federation," "extremism," "enemies of society," and the name "Putin." It also stresses the importance of adhering to international law during military conflicts: "If there is a likelihood of heavy civilian casualties, a military operation should be canceled or postponed."

"Russian textbooks and other paper materials from the occupiers should never be burned," says Stanislav. "They should be collected and recycled, for example, into toilet paper, and copies should be sent to museums so that we do not forget that it is not only bullets that kill."

TRP Senior Legal Advisor Tsvetelina van Benthem notes that Russia’s indoctrination policy in the education system is a clear violation of international law. Both in peacetime and during armed conflict, children must be guaranteed the right to freedom of thought and education, and their identity must be preserved and protected.

"The right to freedom of opinion is fundamental to human dignity, and the protection it provides is far-reaching and profound," says van Benthem. "Under international human rights law, there is an absolute prohibition on interference with freedom of opinion. No restrictions or derogations are allowed. However, we see a Russian policy aimed at manipulating and brainwashing Ukrainian children, erasing their Ukrainian identity."

Yanina Tertychna, Head of the Department for Child Protection and Violence Prevention at the Office of the Prosecutor General, says that Russia’s control over the temporarily occupied territories imposes obligations on it under Article 50 of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

"The occupying power must facilitate the proper functioning of institutions responsible for the care and education of children, and children must be taught by individuals who share their nationality, language, and religion," the prosecutor said.

"Imposing the ethnic community (common language, culture, territory) of the Russian Federation on children through the education system poses a real threat of altering the consciousness of Ukrainian children regarding their own identity by reformatting them from a Ukrainian group to a Russian one, thus indoctrinating them."

"And the tricolor was hanging, and the anthem was sung."

Zhenya Ihnatov was forced to attend the 9th grade at School No.51 in Kherson in 2022. The school had been opened by the occupation administration. Prior to this, his mother had been visited by the Russian military and strongly advised to enroll her children in school.

"There were few people, and the tricolor was hanging, and the anthem was sung. We were also given camouflage-colored backpacks, and my first-grade sister received a small blue backpack with the United Russia logo," Zhenya recalls the September 1 celebrations.

The boy mentions that his class teacher, who came from Crimea, was obsessed with Russia:

"He kept telling us, ‘Russia is our mother! In the Soviet Union... Stalin would have dealt with you properly...’"

In October 2022, the occupation administrations of educational institutions received a letter with recommendations from the Russian Ministry of Education. The letter included guidelines for incorporating Putin’s quotes into the interiors of educational institutions and general recommendations.

It stated that the educational process and comprehensive development of children should align with the Federal State Educational Standards and emphasized the need to display Russian symbols and celebrate Russian national holidays, such as "Day of National Unity," "Constitution Day," "Days of Military Honor of Russia," "Reunification of Crimea with Russia," and others.

Zhenya Ihnatov studied under the Russian program for just over a month because, in November 2022, the Armed Forces of Ukraine liberated Kherson and the right bank of the region from the occupiers. He knows nothing about the fate of his pro-Russian teacher but suspects that he fled to Crimea.

According to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, since the beginning of the full-scale invasion by Russia, juvenile prosecutors have been investigating over 500 criminal cases related to collaboration activities involving the implementation of the aggressor state’s educational standards in Ukraine.

So far, only two indictments have been sent to court in the Kherson region. Among those indicted is Leonila Shchehol, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison. She had taken over as principal of the Shipbuilding Lyceum in Kherson during the occupation.

Our contacts in law enforcement agencies noted that they actually have a much larger number of similar cases that have yet to be properly qualified and documented for court proceedings. At the same time, investigating such cases in the occupied areas on the left bank of the Kherson region is almost impossible, law enforcement officials say.

The head of Kherson’s education department, Natalia Zhurzhenko, is convinced that those who agreed to cooperate with the Russians in 2022 did so voluntarily.

"However, on the left bank, these processes have definitely become forced over time," Zhurzhenko adds. "You cannot treat the right and left banks of the Dnipro in the same way. They are two different universes."

The destruction of Ukrainian identity persists

The context of the war on the left bank of the Kherson region is indeed different, primarily because this part of the region is still under Russian control. After the de-occupation of the right bank, the Dnipro River became the front line, with villages on both sides being destroyed and people dying.

In the early months of the Russian invasion of Kherson region, many families fled to relatives in the villages. For three years now, residents of Kakhovka, Skadovsk, Henichesk, smaller towns, and rural communities have remained under occupation, cut off from the world. The aggressive Russification processes, which became evident after the liberation of the right bank, have become entrenched and systemic on the left bank.

For security reasons, the Ministry of Education of Ukraine does not provide data on the number of students on the left bank who continue their education in Ukrainian schools online. Ukrainian teachers also speak with great caution about this. However, such families do exist, and there are many of them. We managed to speak with some of them on the condition of anonymity.

The daily struggle of these individuals to maintain Ukrainian education under the threat of Russian violence is both striking in its courage and terrifying in its consequences.

"Do you need Ukrainian?" – "No"

Halyna Ivanivna* taught at one of the village schools in the Kakhovka district for many years (names of some individuals have been changed for anonymity – author’s note). The occupation authorities were unable to reopen her home school due to a lack of staff, as most of the teachers had fled west.

Out of a dozen nearby schools in the community, only a few reopened in the 2023-24 school year, and only because the Russians were desperately looking for teachers.

"People in uniform have come to me recently for the third or fourth time, all with the same question: ‘Why don’t you go to work at the school?’" says Halyna. "At first, I told them I had health issues. And then, I am a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. Just between us, do you need this language? They say ‘no’. I would have to speak Russian. You know, I’m not a clown; I’m not going to do it."

Halyna explains that she goes to great lengths to avoid teaching under the Russian curriculum. However, some of her colleagues were forced to work in the occupation schools this year due to increasing pressure from the military.

"They comply because they need to survive. Groceries are very expensive, and there are no jobs. I am very afraid because my children do not attend a Russian school but study online in a Ukrainian school. If they find out about us, we will be in trouble," Halyna Ivanivna says sadly.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, the Education Ombudsman of Ukraine has received about 700 appeals from teachers in the temporarily occupied territories. Former Ombudsman Serhiy Horbachov notes that all educational institutions under occupation have been re-registered as legal entities of the Russian Federation. Children, parents, and teachers are being forced to integrate into the Russian education system

"Parents are required to provide a certificate from the school stating that their child is studying in a Russian school; otherwise, they will not be employed," Horbachov comments. "The military periodically conducts house-to-house inspections to force children to study. If they find Ukrainian links, Ukrainian textbooks, chat rooms about education, or links to Ukrainian educational resources on children’s gadgets, they destroy the gadgets and pressure and threaten the parents."

"My mother had to write an explanation that they were refusing to go to a Ukrainian school."

Larysa Halipenko, a teacher of foreign literature and arts, teaches at a school in Kherson and has students from the left bank. Maksym* is one of them. Together with his family, he left Kherson for a small town on the Black Sea coast. The boy’s mother had two SIM cards: one for her son’s education only.

"The boy’s mother told me, ‘Larysa Oleksandrivna, I’d hide behind the trees, behind the market, insert the second SIM card, take pictures of Maksym’s homework, and send them to the Ukrainian school so that he could graduate,’" says teacher Larysa.

But Maksym cannot obtain a Ukrainian certificate of incomplete secondary education. For now, the family is under occupation, and the document is stored in a school on the right bank with no one available to retrieve it.

According to Maksym’s mother, her son is now forced to attend a Russian school due to pressure from the local occupation authorities. She notes that the Russian school imposes strict control over students’ phones and prohibits the use of Viber, a messenger traditionally used by Ukrainian educators for online learning.

The principal of Kherson School No. 47, Viktoria Khamzaeva, describes the situation of a student from occupied Skadovsk. The girl’s family endures constant searches by the military but continues to educate the child online through a Ukrainian school.

"It’s a private house. While the child is at school, someone is always on duty in the yard. Either grandma or mom would break a glass as a signal if they saw someone, due to the constant rounds and searches. They had already received a warning because the authorities discovered Zoom. The mother had to write an explanation renouncing their attendance at a Ukrainian school," Khamzaeva says.

"Russia destroyed my dreams"

We interviewed high school students who study at a Ukrainian school online and also attend a local Russian school. For security reasons, we do not disclose their place of residence or names.

Our respondents expressed feelings of depression due to homesickness, as they were forced to move across the occupied territories in 2022. For various reasons, they remain on the left bank of the Kherson region, where they resist the Russian re-education efforts and strive to think critically.

However, years of Russian propaganda, coupled with restrictions on freedom of speech and movement, have left their mark. Some students now struggle to clearly define who is to blame for the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and believe that peace could have been achieved if Ukraine had made concessions.

This viewpoint is constantly reiterated by the top political leadership of the Russian Federation.

"I think both countries are to blame. I love Ukraine very much, but I think our president is a bit strange. We could have already reached an agreement with Putin. I know for sure that almost everyone in Crimea definitely does not want to go to Ukraine. I am sure that the LPR and DPR have the same position. What is the point of fighting? We could have given these territories to Russia, and Kherson and Zaporizhzhia should have been given to Ukraine because people here are still waiting for Ukraine," says 16-year-old Karina from the occupied city of N*.

The girl dreams of returning home to her village on the right bank of the Dnipro, but her parents cannot leave her sick grandfather, who is unlikely to survive the long journey.

Oleksandr* also left Kherson with his family in October 2022, just before its liberation. He explains that the family was influenced by Russian propaganda about the dangers posed by Ukrainian armed forces.

"We were afraid that the city would be bombed, so we decided to move to Henichesk," he says.

Sasha completed the 8th grade at a Ukrainian school online. Last year, his mother suggested studying at a Russian school for safety reasons but insisted he should not leave the Ukrainian school as the situation remained uncertain.

According to Sasha, the local Russian school lacks qualified teachers.

"Some of our teachers are not teachers at all. For example, a math teacher used to be a watchman. It has become common here for people without special education to take short courses in Crimea and become teachers," Sasha adds.

He also notes that the school conducts ideological lessons and historical events aimed at justifying the actions of the Russian Federation.

"People usually say that there are Nazis over there, but we are doing fine. I don’t like to always turn to one side; I read different sources. But I still have a dislike for Russia because it destroyed my past life, my dreams, and my plans for the future," Sasha admits.

Currently, Oleksandr still hopes to live in territory controlled by Ukraine, but he openly expresses his fear that his family will be considered traitors.

Ukrainian teachers note that this way of thinking results from Russian narratives that tell residents of occupied territories that no one is waiting for them in Ukraine and that they will be persecuted for "treason."

"Changing the consciousness of adolescents, influencing their moral values and ability to distinguish between good and evil happens gradually and subtly, but it becomes deeply ingrained," says Ukrainian teacher Larysa Halipenko.

Children under occupation are also in constant danger due to ongoing hostilities. Our respondents spoke about explosions, encounters with armed individuals, and military equipment in their vicinity, which has caused them significant anxiety.

Ukrainian certificate is a chance for higher education

Serhiy Horbachov describes what is happening in the occupied territories as educational genocide. The Reckoning Project has documented cases where, due to parents’ refusal to send their children to Russian schools, children have faced fictitious criminal charges and imprisonment. There have also been systematic threats to deprive parents of their parental rights for resisting the new rules imposed by Russia in the occupied territories.

One reason people risk continuing their online education in Ukrainian schools is the option to obtain a Ukrainian secondary education certificate. Parents view this document as a gateway for their child to pursue higher education in Ukraine or Western countries, rather than in Russia.

Currently, it can be argued that Ukrainian children in the occupied territories are subjected to pervasive Russian influence that distorts their perception of reality, even within families that strive to maintain connections with Ukraine.

A team of teachers from temporarily occupied territories, along with legal and psychological experts, has developed the White Book titled "Restoration of the Educational Process in the De-occupied Territories". This document explores various state-level decisions regarding education during the de-occupation process and the potential consequences of each scenario.

Officials note that the White Book also includes proposals for territories that have been under aggressor control for ten years. However, as long as Ukrainian children remain in the occupied cities and villages, preventing their widespread Russification becomes increasingly challenging.

The material was produced as part of The Reckoning Project, an initiative by Ukrainian and international journalists, analysts, and lawyers to document war crimes through 25 in-depth interviews with educators and children who have survived or are currently enduring Russian occupation. For security reasons, some names and locations have been altered.