An Apollo from Zhovti Vody. The life and death of Bohdan Liahov, 19, who fought in a sabotage and reconnaissance unit

One winter day in 2017, Bohdan Liakhov, a 13-year-old schoolboy from Zhovti Vody in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, central Ukraine, came home dishevelled and covered in snow, his face red. When asked what had happened, he replied: "Oh, nothing. I had a snow fight with the guys."

The boys had been playing rough that day: some older kids had practically buried Bohdan and several of his friends in a heap of snow. They’d put up a fierce resistance.

Bohdan – who loved classical music, books, and nice shirts – had dug himself out and started a fight with one of their attackers.

Six years later, Bohdan’s father Oleksandr would have a dream in which Bohdan said to him: "I’m sorry. I couldn’t leave my brothers. I couldn’t not go with them."

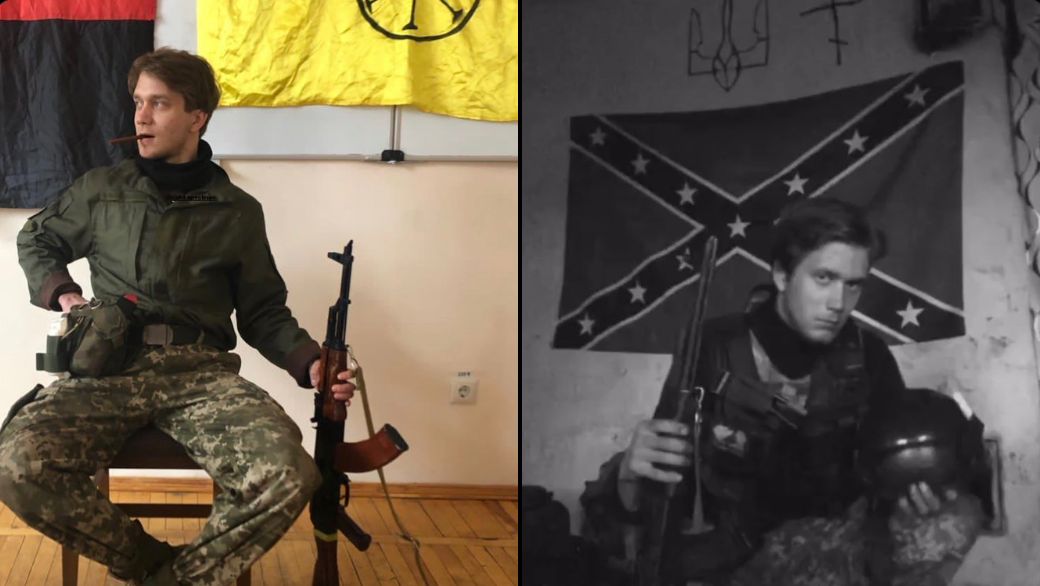

In late 2022, the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) reported that four Ukrainian soldiers had been killed in Russia’s Bryansk Oblast. Bohdan "Apollo" Liakhov was one of them. He was just 19. His parents lost all hope when they saw a photo of the four men’s weapons that was circulating on the internet.

"Somehow, I immediately felt that one of those guns was my son’s," Bohdan’s dad recalls. "I figured it out based on a few things that were typical of him."

Bohdan had written "Courage" in white letters against the black body of the gun. He’d added a quote from the Ukrainian poet Lina Kostenko: "Courage is not for hire." He’d also stuck a picture of the 19th-century poet Taras Shevchenko on the magazine adapter.

The Russians blurred the image of Taras Shevchenko – who played a key role in shaping the idea of Ukrainian statehood and opposed Russian imperial power – in most of the photos they circulated. "They’re afraid of Shevchenko," Bohdan’s dad Oleksandr says. "He became a weapon for people like my son."

Bohdan Liahov was the youngest member of a sabotage and reconnaissance group led by Yurii "Sviatosha" (Saint) Horovets, 34. The other members of the group were Maksym "Nepyipyvo" (Don’t Drink Beer) Mykhailov, 32, and Taras "Tarasii" Karpiuk, 38. All four had volunteered for Dmytro Korchynskyi’s Bratstvo (Brotherhood) Battalion.

Information about the operation they were carrying out behind enemy lines is still classified. But it can be assumed that Horovets, Mykhailov, Karpiuk and Liakhov were among the first Ukrainian soldiers to take the war to Russian territory – long before the Kursk offensive.

"They used to say that it was the only way to win," Bohdan’s mother Maryna recalls. "War has to be taken to the land it came from."

"We had less air defence equipment in late 2022 than we do now," her husband Oleksandr adds. "We couldn’t protect ourselves from aircraft that fired long-range missiles. It was only actions like that [i.e. sabotage operations in Russia – ed.] that could somewhat lessen the impact of [Russian] strategic aircraft on Ukraine."

So what was he like, this real-life, non-mythical Apollo? Ukrainska Pravda has drawn on the memories of Bohdan’s parents, who are both teachers in Zhovti Vody, to tell the story of the young Bohdan Liakhov and his dreams of fame.

Drive

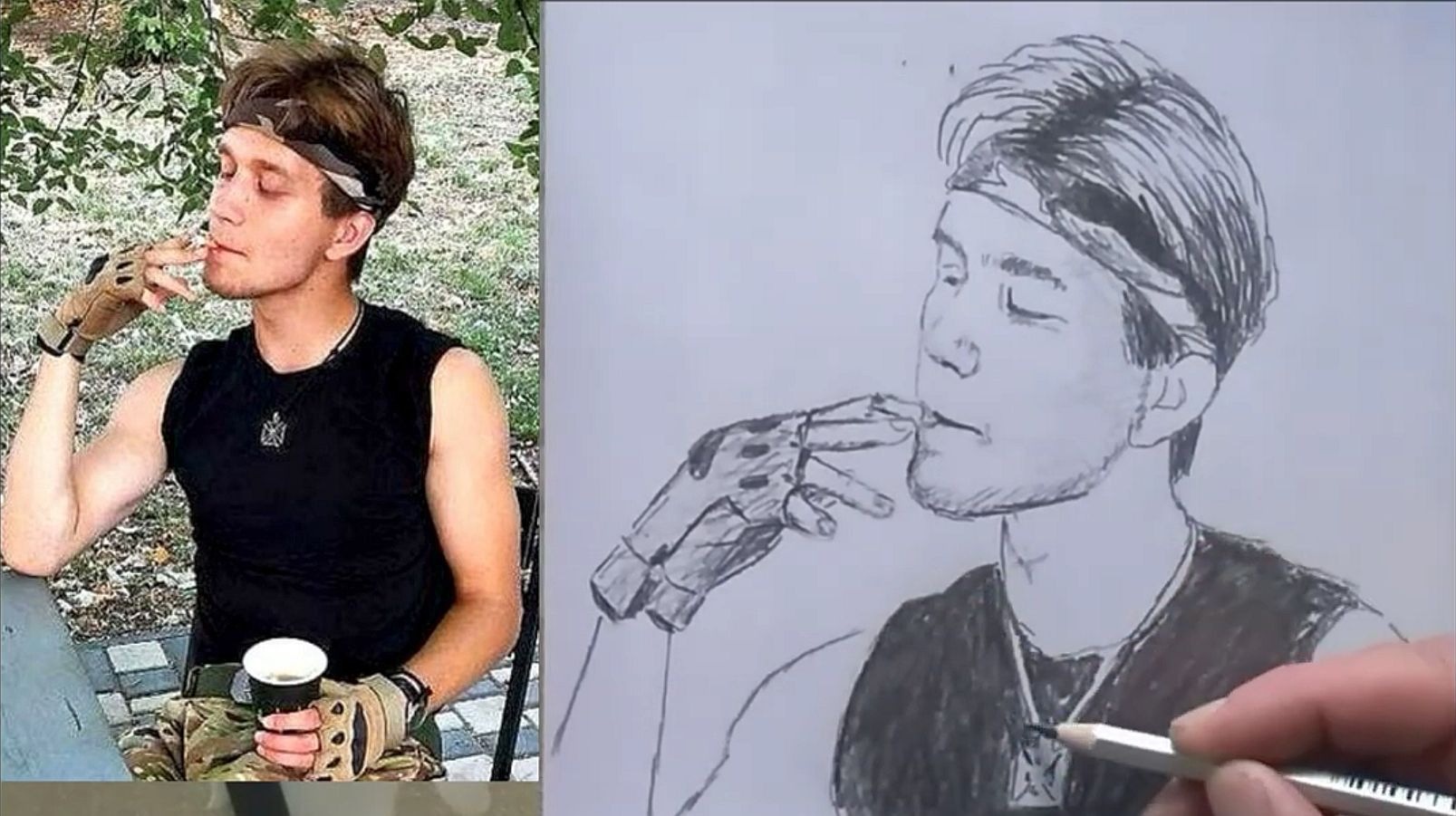

"Radical literature, black shirts, a knife between his teeth, the neoreactionary movement, Winding Refn movies, and a soft spot for Dante. He was an Apollo. Blond and blue-eyed. [...] He looked so good in a military uniform, like a young officer from World War I."

Rina Reznik, combat medic, on Bohdan Liakhov

If it’s true that one isn’t born a hero but rather becomes one, then when did Bohdan Liakhov become a hero?

Many different incidents could serve as Bohdan’s initiation story.

Here he is in kindergarten: he’s told to draw a bird, but goes above and beyond what he’s asked to do. And he does it completely differently to every other kid.

Here he is on his way to music school: a diligent violin player in a restricted city. (Access to Zhovti Vody was formerly restricted by the state due to its uranium mines.)

Here he is, always with an opinion of his own. Never afraid of debate. Always arguing with his dad about history and philosophy. Looking for the best way to organise society.

Here he is three days after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion. He’s 19 and he’s lining up to join the military, queueing at Kyiv’s military enlistment centres. He doesn’t stop when he doesn’t get a spot in the army: he joins the Bratstvo (Brotherhood) Battalion as a volunteer.

Here he is, finally, in his dad’s dream, after he had been killed: "I’m sorry. I couldn’t not go."

Bohdan used to play the violin in between training and carrying out combat missions

"There are always two ways: an easy one and a difficult one," Bohdan’s mother Maryna taught him. "People who choose the easy way live in fear and don’t want to accept responsibility.

If you choose the difficult way, you’ll find success, you’ll be beyond other people’s reach."

"Our son was exactly as we imagined he would be," Maryna says. "Although of course my husband and I didn’t want him to get killed.

He was our only child, long-awaited, born into a loving family.

Now we’re learning how to go on living, how to process our loss. We are proud that our son is part of Ukraine’s victory. I’m certain that Ukraine is already winning."

"Bohdan was attracted to the notion of heroism," his father adds. "He liked to quote from Metaphysics of War by Julius Evola. He wanted to experience something beyond earthly life.

This heroic nature of his became fully apparent after the full-scale invasion started. He felt quite at home and comfortable at war. He felt a thrill."

Manifesto

"In the Italian province of Carnaro, music is a social and religious institution. [...] A noble race is not one that creates a God in its own image but one that creates also the song wherewith to do Him homage."

The 1919 Charter of Carnaro

Bohdan lived and breathed freedom. He fought back against restrictions and pressure from the outside. He knew the world wasn’t perfect and wanted to change it.

At 18, Bohdan got a tattoo of Apollo’s face on the left side of his neck. Later, he had a portrait of Dante tattooed on the left side of his body, just below his ribs.

He wanted to be different and would buy unusual things in second-hand shops. He moved to Kyiv several months before the full-scale invasion, dreaming of becoming a fashion designer.

"I always gave Bohdan lots of praise," his mother Maryna says. "It’s better for a kid to have self-esteem that’s too high than too low. He was a creative person and really took it to heart when things didn’t work out the way he wanted them to.

My husband and I supported our son in everything, and that gave him self-confidence. He wasn’t afraid of trying new things. When he decided to join the military as a volunteer, we eventually came to terms with his decision."

"He didn’t like mediocrity," Bodan’s father adds. "He always said he was going to be famous, but said he had to leave Zhovti Vody to achieve that. He wanted to settle in a city that wasn’t so parochial, somewhere with a thriving cultural life."

Before the full-scale invasion, Bohdan travelled around Ukraine, learning about his country and searching for a place to settle in. He liked Odesa – but Kyiv stole his heart.

He moved to the capital, taking with him his favourite books and a YouTube channel he’d started when he was 13.

His channel, Lyagov Bogdan, had 724 subscribers. His profile picture was a photo of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi [a Ukrainian political and military leader, Hetman of the Ukrainian State (then the official name of Ukraine) in 1918 – ed.]. Bohdan only ever posted two videos: a playlist of classical Ukrainian music from the 18th-20th centuries, and a collection of Ukrainian retro-jazz.

One of the videos is captioned by an ironic manifesto that Bohdan wrote when he was 17: all modern Ukrainian pop singers deserve life imprisonment; the current culture minister and all of his predecessors deserve to be publicly executed with "What Power Art Thou" from Henry Purcell’s opera King Arthur playing in the background.

"He seemed somehow bored in our 21st century," Oleksandr says, as if trying to excuse his son’s radical vision.

Driven by his love of beauty and his uncompromising nature, Bohdan was trying on the role of a cultural dictator. If it had been up to him, he would have elevated music above all else at the government policy level.

There’s an echo of the past here. Some 100 years ago, after the Austro-Hungarian Empire had fallen apart, Gabriele D’Annunzio, a poet and military pilot, set up the Italian Regency of Carnaro in the city of Fiume with himself as Duce.

In his bizarre constitution, which Bohdan was familiar with, D’Annunzio wrote:

"In every commune of the province there will be a choral society and an orchestra subsidised by the State. [...] The great orchestral and choral celebrations will be entirely free; in the language of the Church – a gift of God."

Word and deed

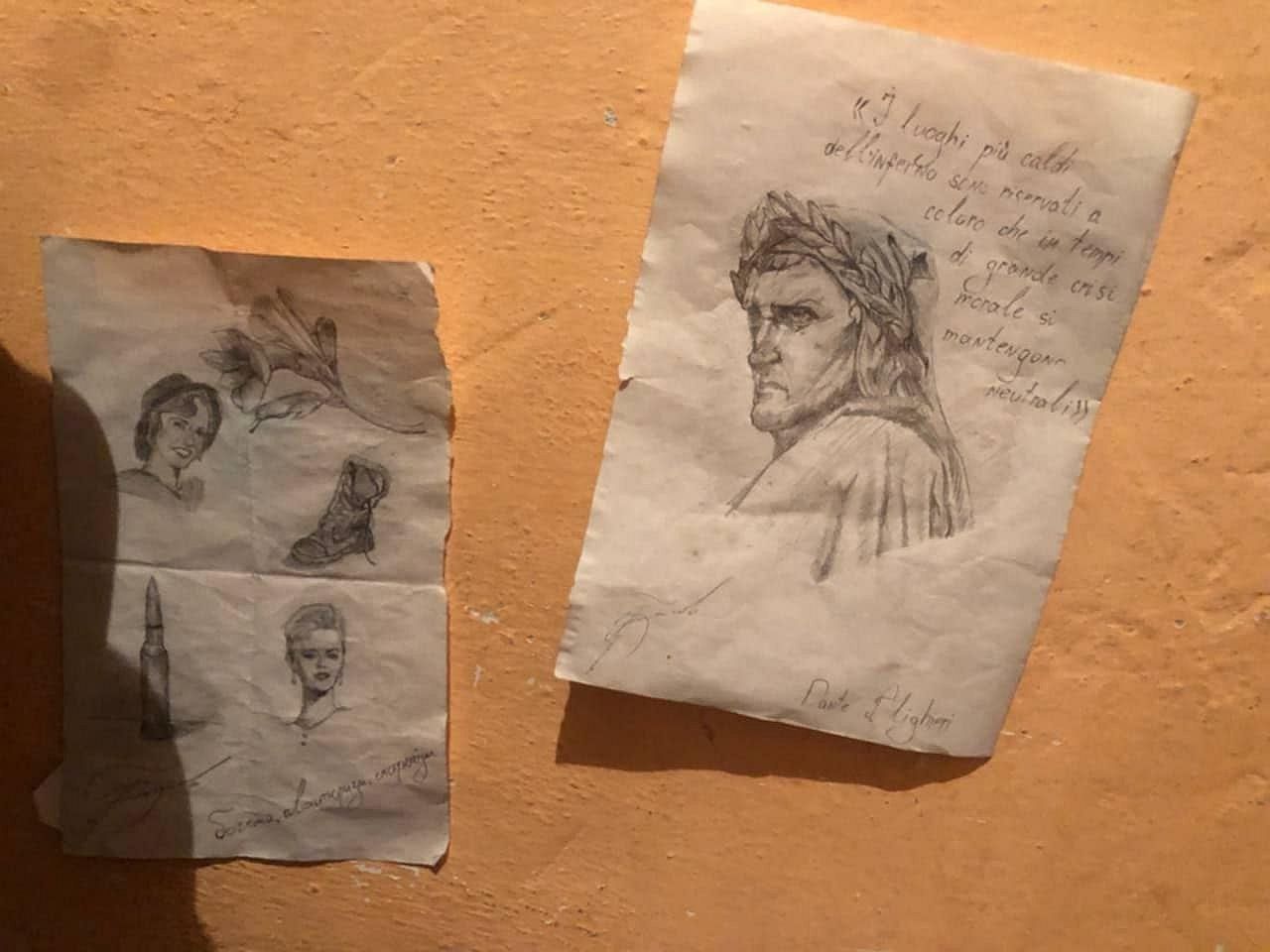

"The hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in times of great moral crisis, maintain their neutrality."

Dante Alighieri. Bohdan wrote this quotation on a portrait of Dante he drew while at the front

The only conventional thing about the shrine that Bohdan created in his room was its location: the wall above his computer desk.

The portraits he printed out and stuck to the wall meant little to kids his own age: Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, Freud, Nietzsche, Mozart, Bach, H.P. Lovecraft, and Viacheslav Lypynskyi – the true underground as far as young people are concerned.

Bohdan’s efforts to change the world always started with himself and his surroundings. He would call his mum from Kyiv and say: "Mum, the guys here are borrowing books from my library."

"He was really proud when he got to introduce someone to something that was new to them," Maryna says. "When he joined the battalion and briefly came home in May, the only thing he took back to Kyiv with him was a rucksack full of books."

In the capital, Bohdan felt he was in his element. The answers he’d been searching for in the work of philosophers from centuries ago suddenly seemed almost within his reach.

"He had long been preoccupied with whether word or deed was more important," Oleksandr recalls. "We talked about it during our last conversation before his mission.

He said that a person should be judged by their actions. I argued that a thought, a word, always preempts action. Your future deeds will be whatever you choose them to be. But he stood his ground."

Bohdan’s deeds matched his words. When his parents begged him to take a train back to Zhovti Vody in February 2022, Bohdan insisted: "No. I’m staying here. Ukraine’s future is being decided here. History is being written in Kyiv, right now."

The Kyivite

"Dear Bohdan Oleksandrovych,

With faith in my heart, my best wishes, and hope for victory,

Sincerely, Konverskyi."

Anatolii Konverskyi, Dean of Philosophy at Kyiv National University, gave Bohdan a copy of his book, Critical Thinking, when Bohdan was manning a checkpoint near the university, and wrote this dedication in it

Full-bodied but well-balanced tannins.

Floral notes with hints of rosemary, mint and oregano.

A wine expert tasting Brunello di Montalcino would point out even more: notes of balsamic vinegar, red pepper flakes, and Maraschino. As it ages, the wine acquires hints of tobacco, leather, carob, and fig.

A month and a half before he was killed, Bohdan said in an interview: "I don’t make plans. I’ve always found it funny when people talk about their plans, forgetting that death is always near."

He immediately added, however, that after Ukraine’s victory, he wanted to visit southern Italy. To watch the sun set over the Mediterranean while sipping a glass of Brunello di Montalcino.

"He always did what he wanted," Bohdan’s mother says. "And we always just wanted him to be happy.

My heart ached when Bohdan joined the battalion. He’d call and say: ‘But Mum, you always wanted me to be happy. I’m happy now. You can’t even imagine the kinds of people I’ve got to know here!’"

The last time Bohdan visited his parents in Zhovti Vody was in late October 2022, to pick up some boots and other useful bits of equipment his parents had bought for him.

His mum suggested they get a photo together against the backdrop of the autumn trees – their leaves had not yet fallen. Bohdan insisted on taking a selfie in front of a monument to Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, Ivan Bohun and Maksym Kryvonis [Cossack military commanders – ed.].

"Don’t worry," Bohdan told his mother. "I am Bohdan. Remember you told me when I was a kid that I was God-given [the literal meaning of the name Bohdan – ed.]. I’m one of the lucky ones. Nothing will happen to me."

The ancient Greek god Apollo, up on Mount Olympus, could see the future. But that can’t be difficult if you’re the son of Zeus and Leto.

"Bohdan said things that seem prophetic now," his mother Maryna recalls. "He said he wouldn’t be able to visit us because he would be far away. He said we could stay with him sometimes.

Now we visit him in Kyiv."

"I’m staying here to defend Kyiv, and when I’m done, they’ll give me an apartment here," Oleksandr remembers his son saying. "That was based on his childishly idealistic worldview.

He was captivated by the dream of becoming a true Kyivite, of settling in this beautiful city. And tragically, his dream came true. He will remain in Kyiv forever now, in a very beautiful spot at the Baikove Cemetery.

I hope that now he can really count as one of the Kyivites who gave their lives for victory."

Yevhen Rudenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Translated by Olya Loza

Edited by Teresa Pearce