Commander-in-Chief Syrskyi's raid: how the Ukrainian offensive in Russia's Kursk Oblast is progressing and what to expect next

Nowhere is the fragility of borders more evident than at the Ukrainian-Russian border crossing point at Yunakivka-Sudzha in Ukraine’s Sumy Oblast these days. Once a place of strict passport control, it has become a very specific visa-free zone that can only be used by one category of people—the defence forces.

Instead of a passport, they now ask for a password. And instead of welcome posters at the entrance, you’ll come across Russian administrative buildings that have been smashed by Ukrainian artillery. Soldiers from the 80th Brigade told Ukrainska Pravda that the buildings were destroyed by the defence forces on the first day of the operation. Most of the Russian security forces inside the buildings surrendered.

Beyond the checkpoint are a couple of tiny villages; the town of Sudzha – population 15,000 – which has now become world-famous; and several dozen square kilometres of Russian territory that have been under the control of the Ukrainian defence forces for a week.

On 10 August, day five of the Ukrainian forces’ offensive deep into Russia, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy acknowledged that Ukraine had pushed the war into the aggressor's land. On 14 August, he added that the operation was ongoing and that its strategic goal was being achieved.

Ukrainska Pravda decided to find out what the defence forces’ offensive operation in Russia’s Kursk Oblast is all about: the intentions behind it, how it could develop, and what reaction it may cause.

Interim results of the operation:

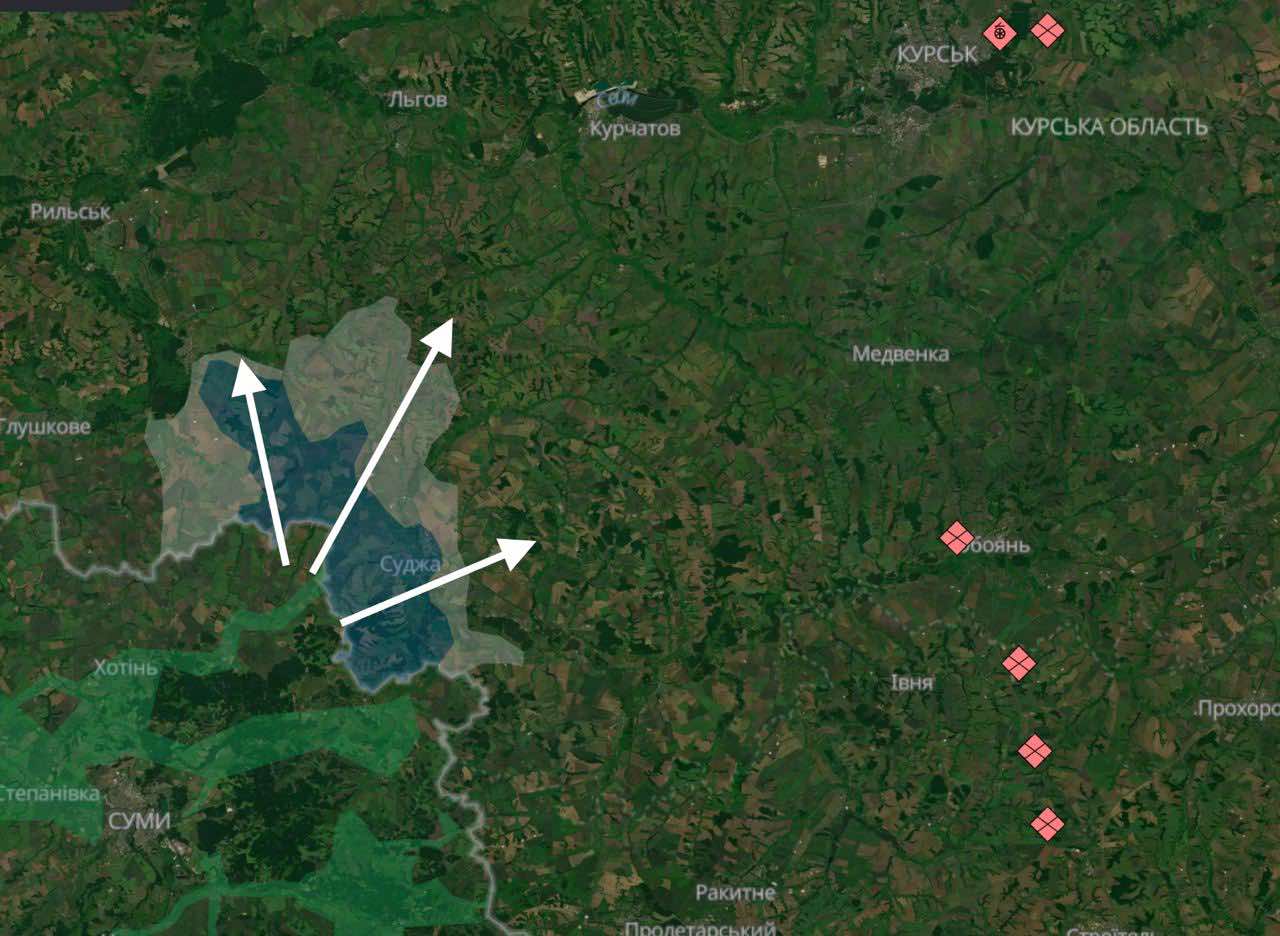

- the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine noted that as of the evening of 13 August, the defence forces had taken control of 74 settlements in Kursk Oblast;

- the depth of the Ukrainian units’ advance into Russian territory ranges from 2 to 35 km;

- there are 3-4 directions of movement in total, the most successful of which so far is the offensive towards the village of Korenevo. Tanks, self-propelled artillery systems and armoured personnel carriers continue to move towards the border;

- the defence forces have suffered minimal losses, according to Ukrainska Pravda sources in one of the brigades participating in the operation, as well as a source familiar with the number of casualties.

Preparation, tasks and units

On the evening of 28 July, soldiers from the 80th Brigade contacted Ukrainska Pravda with a rather sudden request for us to publish an appeal in support of their then commander, Colonel Emil Ishkulov, who was facing dismissal.

All that was known about this command decision was that Ishkulov, who respects the military hierarchy, had refused to carry out a task set by Oleksandr Syrskyi, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He said it was disproportionate to the human resources of the brigade.

A couple of days later, on 6 August, it became clear exactly what Ishkulov had refused to do when Ukrainian forces – including the 80th Brigade, under the leadership of a new commander, Pavlo Rozlach – went on a raid into Russian territory.

Few people – including the Russian command – expected this turn of events. And only a small group of people familiar with the planning understood how large the operation would be.

The information vacuum has given rise to many questions. Is this an offensive comparable to the border breach into Belgorod Oblast by the Russian Volunteer Corps? Is it an attempt to raid the Russian rear? Or is it an operation to take control of a strip of Russian territory to prevent attacks on Ukrainian land?

"Syrskyi’s Raid" is what Ukrainska Pravda’s sources in the defence forces who are involved in the operation call it. Roman Kostenko, a member of the Verkhovna Rada (Parliamentary) Defence Committee and former Special Group Alpha member, says the operation did indeed have clear signs of a raid, especially in the early days. It was an entry into enemy territory, destroying military targets on the way and deploying powerful landing forces.

This is not a classic frontal assault, but a cunning and so far successful manoeuvre by the defence forces, very much in Colonel General Syrskyi’s style, which first emerged during the Kharkiv offensive he led in the autumn of 2022.

Back then, Ukraine liberated a swathe of territory from Balakliia and Izium in the south of Kharkiv Oblast to Kupiansk in the north. It did so after much planning, attacking the place with the lowest concentration of Russian forces and making rapid breakthroughs with small, highly mobile strike groups. The hallmarks of that operation were unexpected boldness and willingness to take risks.

If one adds the intensive use of reconnaissance and attack drones to those tactics, this will accurately describe how the current Kursk offensive is being conducted.

In some ways it "mirrors" Russia's recent attempted offensive in Kharkiv Oblast. The only difference is that when the Russians attacked Lyptsi and Vovchansk, they ran into highly motivated Ukrainian forces who began to crush them from day one of the offensive.

The Ukrainian brigades in Russia’s Kursk Oblast planned their offensive in such a way that they did not face a large and echeloned defence. They were met by Russian border guards, conscripts, staff soldiers, and scattered Kadyrovite fighters in the forests [Ramzan Kadyrov is the leader of Chechnya and is a close associate and supporter of Putin – ed.]. That is why the Ukrainian offensive began in this area.

As open sources indicate, the core of the Kursk operation was formed by two brigades of the Air Assault Forces – the legendary and mighty 80th Brigade, based in Lviv, and the Chernivtsi-based 82nd Brigade, which was formed last year. In the second week of the operation, they were joined by part of the equally battle-hardened 95th Air Assault Brigade.

This is in stark contrast to the approach taken in June 2023 during the Melitopol offensive, where the main striking force was the newly formed, inexperienced 47th Magura Brigade.

Following those brigades, at least two Ground Forces brigades formed during the full-scale invasion, the 22nd and the 61st, mopped up the area and held the positions in Kursk Oblast.

How long the defence forces will be able to control and use the territories they currently occupy for their own purposes will depend on the extent to which the two Ground Forces brigades are able to dig trenches and gain a foothold on the lines captured by the Air Assault brigades.

After all, sooner or later the Russians will gather their reserves and counterattack in the towns and villages of Kursk Oblast. Meanwhile, Zelenskyy is already allowing the defence forces to deploy a form of "local government" there – military commandants’ offices.

As of 15 August, the Ukrainian forces are continuing their offensive along the motorway from the captured town of Sudzha towards Kursk, as well as towards the villages of Korenevo and Pogrebki.

For several days now, Syrskyi has been reporting to President Zelenskyy on the latest territories and settlements the defenders have taken control of.

The question that logically arises is: how far do the Ukrainian forces plan to advance? In the early days of the operation, Ukrainians on social media were even talking about capturing the Kursk Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) and possibly "exchanging" it for the currently Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia NPP.

From a political point of view, that scenario looks far-fetched in the extreme. In addition, an analysis of the offensive’s military component shows that Ukraine does not aim to capture the Kursk NPP, at least at this stage. Holding it in a circular defence mode hundreds of kilometres away from the border and supply bases, with the risk of constant attacks and encirclement, would require much larger forces than the Ukrainian Armed Forces have deployed.

However, the ongoing advance of Ukrainian units towards Kursk may indicate that the Ukrainian Armed Forces want to constrain Russian forces in the area. From a strategic point of view, it would be useful to cut off the E105 international motorway, which supplies Russian forces near Belgorod.

If the Russian occupation forces there had lost support from the north, it would have been much more difficult – perhaps impossible – for them to threaten Kharkiv and hold the occupied areas of Kharkiv Oblast.

Russian forces have now begun to dig in almost on the outskirts of Kursk as they wait for reinforcements.

Russian forces are rapidly digging a network of trenches in Kursk Oblast, with only one catch:

— OSINTtechnical (@Osinttechnical) August 14, 2024

The trenches are 45km behind the border.

Russian forces have been developing a trench network that, if fallen back to, would cede Ukraine a massive amount of territory. pic.twitter.com/dXje3n1qn8

It can be assumed that during the planning, Syrskyi hoped that the Russians would take reinforcements from the two hottest areas for the Ukrainian Armed Forces – Toretsk and Pokrovsk – to defend Kursk.

Ukrainska Pravda sources in the Luhansk Operational Tactical Group of Forces, which is fighting on the Pokrovsk front, said that the Ukrainian defenders felt no relief in combat actions during the week of the operation. The Russians continue to assault the burning city of Toretsk and bombard it with aerial bombs, and they are advancing in the villages on the approach to Pokrovsk almost every day.

While Russian troops do not have sufficient forces to counterattack, the Ukrainian Armed Forces have begun building defence lines, indicating their intention to hold the occupied territories.

One of the less obvious but important effects of the raid is the sense of enthusiasm among the Ukrainian military and the belief that they can change the situation at the front.

Ukrainska Pravda journalists who spoke to soldiers from the 80th Brigade during the week could see how the soldiers, previously exhausted by the Bakhmut front, were eager to move forward and, most importantly, to take the war to Russian territory.

"Ahhh, we've captured a tank!", "We have an urgent evacuation" [hinting at a new batch of prisoners – ed.], "We need to move the base forward" – these are some of the dozens of joyful messages that the journalists received this week.

What the experts are predicting

Serhii Zhurets, director of the information and consulting company Defense Express, says Russia's current gathering of forces to respond to the Kursk operation reminds him of a solianka – a soup that’s a hodgepodge of different ingredients.

The Russians are redeploying battalions from the 810th Brigade (known for its high casualty rate), the international Pyatnashka Brigade, Kadyrov's Akhmat unit, some battalions that were involved in the invasion of Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts, and even some units from Kaliningrad, leaving the semi-exclave "demilitarised". At the same time, they are trying not to reduce the pressure in Ukraine’s east.

However, this hodgepodge is not enough to force the Ukrainian defence forces to retreat from the territories they occupy in Kursk Oblast. To do that, Zhurets estimates that Russia needs to deploy approximately 30,000-40,000 troops to Kursk. In the meantime, the Russians are amassing reserves and trying to block the advance of Ukrainian troops on the flanks.

"The perfect scenario for us now would be for the enemy to withdraw its forces from other areas and send them to this [the Kursk] front, exposing its reserves," says Zhurets. "Even this shift would be advantageous for other areas of the front.

Regarding the strategies for Ukraine's defence forces, both flanking and deep advance tactics are viable options. However, the deeper the advance into Russian territory, the higher the risk to our logistics and the [increased potential] for flanking attacks [by Russian forces].

Therefore, it makes more sense now for us to try to expand the offensive to the west and east. By advancing along the flanks, we can extend the Rylsk-Korenevo-Sudzha line, which reduces the length of the front line by about 100 km and runs through Russian territory. It has a limited number of manageable roads. It has rivers suitable for constructing defensive positions. This line could potentially be maintained by Ukrainian forces as a sort of intermediate defensive position for some time," Zhurets notes.

The Ukrainian forces’ actions in Kursk Oblast remind Zhurets of the tactics employed by the Soviet army during World War II. Like the Kursk operation of that era, the current strategy involves forming an operational manoeuvre group, where multiple mobile brigades are assembled to breach enemy defences, create a new front and proceed to act based on their own capabilities.

"The blending of the best World War II strategies, which I think Syrskyi studied at the academy, has been creatively worked on, enhanced by modern technological solutions, and has produced the maximum result," Zhurets believes. "This ensured a shock for the enemy and a surprise for our partners."

Ukraine's partners have reacted in various ways: US President Joe Biden acknowledged the events, noting that the Ukrainian attack presents a real dilemma for Kremlin ruler Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile, members of a US bipartisan delegation on an official visit to Kyiv expressed admiration, with one remarking, "Putin started this; kick his ass!"

In her discussions with politicians and experts abroad over the past few months, Hanna Shelest, Director of Security Studies at the Foreign Policy Council Ukrainian Prism, has felt a strong sense of déjà vu from the early months of the full-scale invasion. Then, as now, there was a significant amount of advice from foreign observers urging Ukraine to negotiate and reach a compromise with Russia.

However, as the Kursk operation unfolded, such defeatist sentiments came to naught.

"Analysing all the conversations I’ve had in many capitals in and outside Europe over the past six months, it seems to me that the main fear was that these countries would be drawn into the war," Shelest says. "That is, [they dreaded] a strike on the territory of a NATO member state, an escalation or provocation.

And suddenly, when an operation does take place which is a clear case of escalation, we see either tacit support or even approving statements to the effect that Ukraine has the right to defend itself. Prior to this, fear had deterred many of our partners from supplying weapons or authorising [their use – ed.]. The main sceptics are now beginning to overcome this psychological barrier, though it won’t happen overnight," she stressed.

So far, Ukraine's successes on Russian territory have not been compelling enough for the UK, for instance, to authorise the use of long-range missiles deep within Russia. However, Shelest notes that it is only since May of this year that the Ukrainian military has been allowed to use US-made HIMARS multiple-launch rocket systems to strike Russian targets (in defence against the offensive in Kharkiv Oblast). In her view, an extension of authorisation for long-range missiles is merely a matter of time.

The psychological impact of the Kursk operation is as significant as its operational aspects on the battlefield, former Ukrainian foreign minister Pavlo Klimkin emphasises. He believes that the success of the Ukrainian forces highlights the Kremlin's vulnerability and alters perceptions of both contemporary Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin.

"It's hard for the vulnerable to dictate their terms. This situation creates a psychological and political context that could shift negotiations to follow a different logic.

Now, most likely, there will be an escalation, a raising of the stakes. If Russia raises the stakes, then the West will get a kind of opportunity to raise the stakes for itself," Klimkin predicts. "Through escalation, we can come to a better understanding of who wants to negotiate on what terms, and who does not want to negotiate.

These events will definitely give us positions [in possible negotiations – UP] that are no worse and, in the long run, perhaps even better ones. I don't see any critical losses for us, but I do see various scenarios where we could emerge victorious."

The social media reaction to the war in Russia's Sudzha and Kursk

The Russian media and the authorities began to recover from Ukraine's offensive in Kursk on the second or third day.

Initially, the propagandists echoed official statements about mobilising reserves and stabilising the situation, using old footage from Donbas as evidence of "successful strikes" on Ukrainian convoys in Kursk Oblast.

When it became clear that Ukrainian forces had not (or at least not yet) reached Kurchatov, the Kursk nuclear power plant, or the city of Kursk, more commentators began appearing in Moscow TV studios. One of their main reassuring messages in week two of the Ukrainian operation was that the offensive had been "planned by NATO generals", but that this plan was "absolutely disastrous and inept".

However much propaganda lulls the Russian public, its spell is weakening in Kursk Oblast itself and on local Telegram channels such as Sudzha Rodnaya (Native Sudzha), Kursk Bomond, etc. The mood in these online groups is reminiscent of scenes from the Soviet comedy Garage. [This 1979 film is a satirical portrayal of a group of people in a cooperative garage society who are forced to negotiate and argue over which members will lose their garage spots due to a reduction in available spaces. The film captures the absurdity and tensions of group decision-making and reflects social relations in Soviet society – ed.]

In keeping with a long-standing Russian tradition, Kursk residents looking for scapegoats have largely directed their criticism at the local authorities. The questions they have for the government include: why were there no fortifications on the border, despite the billions of roubles spent; why was no evacuation from the settlements organised; where are the shelters; how are people supposed to get to work when all the public transport in Kursk comes to a halt during air raids; and why is there no water?

Locals are hotly debating the sudden surge in rental prices for refugees in Kursk, as well as the exorbitant fares charged by taxi drivers who are taking advantage of the transport stoppages during the frequent air raids.

Many of the questions being asked in local online chats are also addressed to Moscow itself.

The "people of the Russian heartland" are outraged by the high number of conscripts in this part of the war zone. They are also asking how they are supposed to survive on the RUB 10,000 (approximately US$112) that Putin has promised the refugees.

These folks don’t understand where the "red lines" are actually drawn and why the Kremlin has not yet taught the White House a lesson. They are also questioning why Kyiv and its decision-making centres haven't yet been wiped off the map.

These people are frustrated that Russia's centralised TV channels mispronounce Kursk place names and continue to air entertainment programmes. At the same time, people in Moscow are sitting around in coffee shops enjoying life, seemingly unaffected.

The war's shift to Russian territory, particularly during the early days of fighting in Kursk Oblast, has exposed the disorganisation and lack of unity among the population. Despite this, the people of Kursk are making efforts to support and cooperate with each other directly in response to the crisis and the inaction of the authorities.

The Telegram channel Kursk Beau Monde is filled with expressions of gratitude, such as "God bless the driver who picked me up and took me home without charging a penny." Meanwhile, another Telegram channel, Native Sudzha, has been fundraising for a UAZ Bukhanka vehicle to support the Russian special forces.

A fabricated story circulated by the Russian media claimed that "pregnant Nina Kuznetsova" was "shot by the Ukrainians as she tried to escape from Sudzha by car", and that her body is supposedly "impossible to retrieve because the Ukrainians won’t give it back". This tale is the ultimate illustration of how helpless the Russians are as the war reaches their territory.

One week on from the start of Ukraine’s operation in Kursk Oblast, fewer voices on local Telegram channels are asking, "Does anyone know whether Nina was taken away from Sudzha?" But they have yet to receive an answer.

***

Perhaps the main question that comes up in discussions about the Ukrainian operation in Kursk is why exactly Ukraine needs to take control of Russian villages and towns.

Apart from the military reasons described above, there are several others.

Firstly, this is a mirror response to Putin's demands that Ukraine "recognise the new geopolitical reality" and give up the occupied territories. By the same logic, the "nuclear superpower" should also forget about the Russian settlements that have been liberated from Putin's regime by Ukrainian forces.

Secondly, it is a matter of justice: that an aggressor country that has waged war on another's land should experience it within its own borders.

Anyone who disregards the inviolability of borders should be prepared to see their borders crossed at any point. A country that has deprived millions of people of their homes must face an avalanche of its own angry refugees.

Finally, this is perhaps the most high-profile attempt to politically destabilise the Russian government.

The Kremlin regime can maintain its stability as long as it provides the average Russian with bread on the table in exchange for the ability to monopolistically engage in politics and war.

The onset of a deep economic crisis, compounded by hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people, may have unpredictable consequences for the Russian regime.

As Zelenskyy wryly put it, Putin's rule began with the Kursk submarine disaster, and it could end with another Kursk tragedy – this time with the city.

Written by: Olha Kyrylenko, Roman Romaniuk, Rustem Khalilov and Yevhen Rudenko

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska and Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Teresa Pearce