War of guided aerial bombs. Why Ukraine is talking about its own production of guided bombs

The phrase "Russian forces attack with guided aerial bombs (GAB)" has, unfortunately, become a common term in news reports by Ukraine's General Staff and military-civilian administrations.

Settlements in Kharkiv, Donetsk, Sumy, Kherson, Chernihiv and Zaporizhzhia oblasts suffer from dozens of airstrikes every day, and the number of UAVs that attack Ukrainian cities and villages is estimated at hundreds daily.

The Department of Public Relations of the Armed Forces of Ukraine told Ukrainska Pravda that Russia used more than 10,000 UAVs against Ukraine between 1 January and 31 May 2024. This data shows that the use of aerial bombs has increased almost 20 times compared to the whole year 2023.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that the Russians are already using more than 3,000 guided aerial bombs per month to attack Ukraine, and this figure is constantly growing.

The Ukrainian defence forces also use guided aerial bombs, but compared to Russia, they use a much smaller amount of ammunition provided by Western partners.

However, the situation may change in the near future.

Brigadier General Serhii Holubtsov, chief of aircraft of the Air Force Command of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, said on 9 June that the Armed Forces of Ukraine will begin testing guided bombs of Ukrainian production in a few weeks.

Ukrainska Pravda (UP) investigated how guided aerial bombs affect the course of the war, why the production of Ukrainian aerial bombs was not previously spoken about, and whether the Air Force is able to achieve parity in the use of such munitions.

Russian GABs are a difficult headache to get rid of

The abbreviation GAB (guided aerial bomb) became well known in Ukraine in the spring of 2023. Back then, the Russians began using the UMPB (unified multi-purpose glide bomb), which they attached to their FAB-250, FAB-500, and FAB-1500 high-explosive bombs (the number stands for the weight of the bomb in kilograms). Russia has accumulated tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of such munitions since the Soviet era.

UMPBs represent some kind of "wings" with a satellite gunner and a control module that are attached to the bomb, allowing it to turn from an uncontrolled bomb into a full-fledged GAB. To avoid being affected by Ukrainian electronic warfare systems, they are also equipped with Kometa-M digital grids.

The key advantage of GABs is their low price. One such "bomb with wings" can cost up to US$20,000. Meanwhile, most of the long-range cruise missiles used by Russia to hit Ukraine cost an average of about US$1 million.

Another advantage is the range. Aircraft can launch GAMs from an altitude of 10-12 km and a distance of 40-60 km (sometimes up to 80 km), which, for example, has been a major problem in Kharkiv recently. The aircraft that drop them do not enter the range covered by the air defence systems of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, which support troops on the battlefield (for example, the Osa and Strela-10 surface-to-air missile systems have a range of 8-10 km).

Neither will the Air Force's short- and medium-range air defences, such as Buk, Iris-T and NASAMS, which operate at 25-35 km, help destroy them.

American JDAM-ER and French AASM

While the Russians use GABs in huge numbers, Ukraine lags behind in this aspect. However, the Ukrainian Air Force also has samples of Western weapons in its arsenal, which, unlike Russian ones, can truly be called "smart bombs".

"The Russians often drop their bombs randomly, without regard to the accuracy of their bombs, so although they often cause significant damage, they may not achieve their intended target. Western weapons are much more accurate," aviation expert Kostiantyn Kryvolap explains to UP.

When one speaks of Western aerial bombs, the first thing that comes to mind is the American JDAM-ER, a set of equipment with an inertial navigation system and GPS-based guidance system that turns simple unguided bombs into guided aerial bombs. In fact, the Russian UMPB was a response to these devices.

The US version shows that the system can be connected to bombs of various weights and sizes, ranging from 230 kg to 900 kg. The range is up to 72 km.

Ukraine began using JDAMs in the spring of 2023, adapting them for MiG-29 and Su-27 fighters. The number of munitions transferred was not disclosed and their use was not officially confirmed, but in July 2023, Mykola Oleshchuk, Commander of the Ukrainian Air Force, showed one of these bombs attached to a pylon of a Ukrainian aircraft.

There were reports this spring that Western munitions were seriously affected by Russian GPS jamming systems. In response, the United States ordered new sensors that will enable Ukraine's JDAM-ER bombs to hit Russian electronic warfare systems.

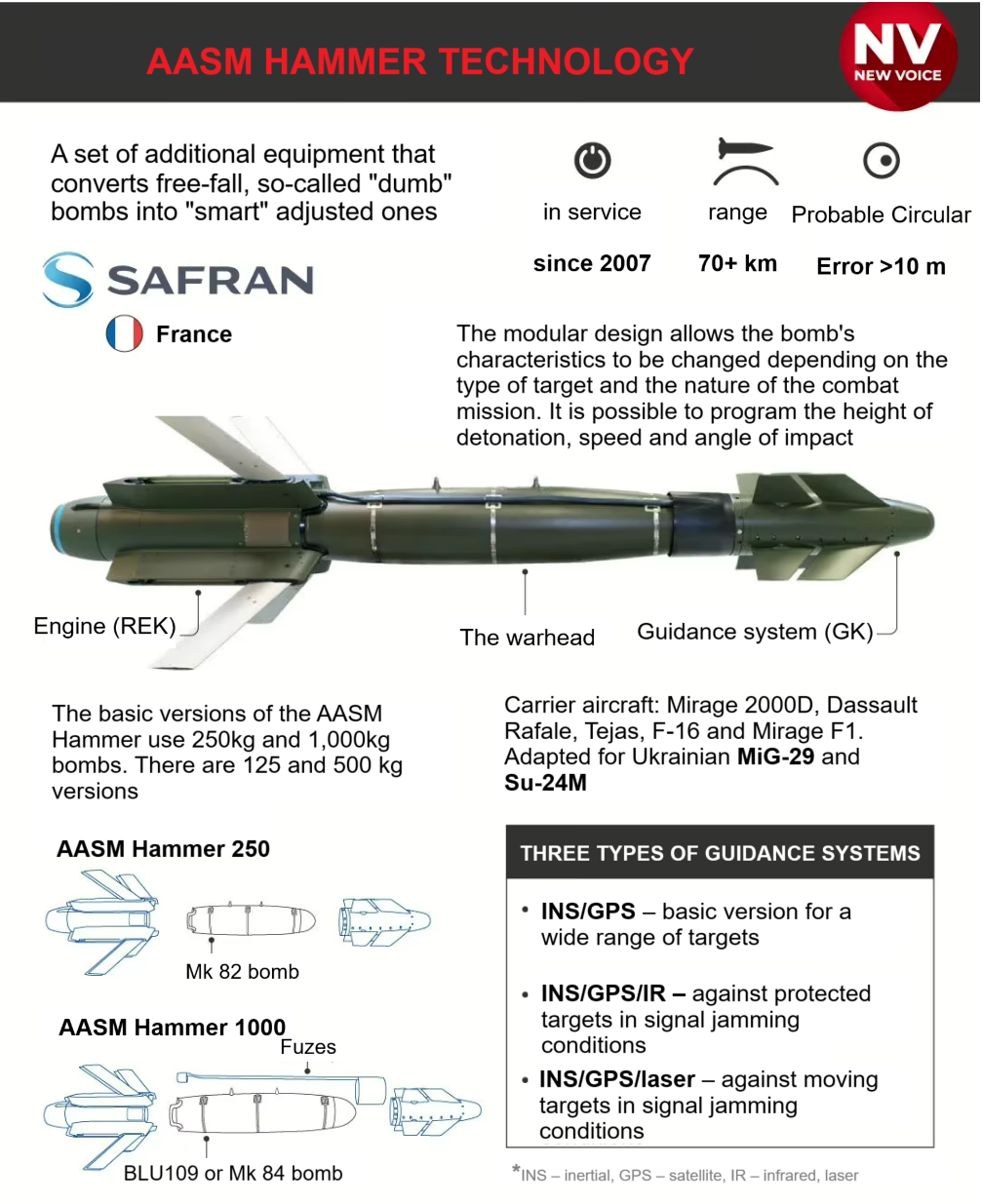

Against the backdrop of delays in the supply of weapons from the United States, in early 2024, France began to provide Ukraine with its version of the AASM (or HAMMER in English).

The peculiarity of this aerial bomb is that it is modular and consists of a guidance system at the front and a range extension system at the rear, which can be attached to different types of unguided bombs.

The standard version is a 250-kilogram bomb, but it is possible to work with 125-, 500- and 1,000-kilogram versions equipped with hybrid navigation systems.

The maximum range of such a bomb is up to 70 kilometres. The problem with the transfer of such munitions was that their "native" carriers are French Dassault Rafale and Mirage-2000 fighters, which Emmanuel Macron has already promised to provide to Ukraine. However, similarly to JDAM, AASMs were adapted for Soviet-made fighters (MiG and Su jets), which are in service in Ukraine. In particular, these bombs were adapted for Ukrainian Su-25 attack aircraft.

In addition to these two heavy-duty bombs, recent reports suggest that Ukraine’s Air Force has been deploying small-diameter bombs (SDB), such as GBU-39 and GBU-39/B.

These bombs weigh 130 kilograms and can travel up to 110 kilometres. They have wings that unfold in flight, which allows them to strike targets much further away.

These bombs are also equipped with a tungsten tip that allows them to permeate concrete.

Is there any point in making an exact analogue of the UMPB?

Western ammunition is, for sure, a good thing. However, the large number of GABs that Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union raises a logical question: why is the production of Ukrainian GABs only now being discussed? Especially since the experts interviewed by the Ukrainska Pravda agree that Russian GABs are not unique.

The answer lies primarily in the difficulties in operating the GABs with the aircraft available in Ukraine.

It is clear that the Su-30M, Su-34 and Su-35 fighter jets used by the Russians for dropping guided bombs are technologically far superior to the Ukrainian Su-24M, Su-27 and MiG-29 jets. Ukraine’s outdated fighter jets struggle significantly more when operating in the face of the active resistance of Russian air defence systems, which include numerous long-range systems like the S-300 and S-400.

Although Ukraine still has a sufficient fleet of aircraft and bombs, it makes no sense to simply copy the Russian UMPB, undamaged samples of which periodically end up with the Ukrainian Armed Forces due to the malfunctioning of old Soviet munitions.

The Ukrainian Air Force has not yet disclosed the details of the design of Ukrainian guided bombs or the timeline for their deployment. However, UP sources in the military and political leadership assured that "there is no question of blindly copying the Russians".

What should Ukrainian guided bombs be like

Anatolii Khrapchynskyi, Deputy Director General of a company producing electronic warfare systems, asserts that the development of Ukrainian guided bombs is a direct result of the evolutionary progress within the Ukrainian defence industry in recent years.

"Actually, even though we receive some weaponry from Western partners, we have started doing a lot ourselves. Over the past year, we have seen the extensive use of various types of domestic UAVs, received new artillery samples, and are starting to produce a large quantity of electronic warfare equipment. There has been a demand for our JDAM," he notes.

Another aircraft expert, Kostiantyn Kryvolap, believes that initially Ukraine relied more on Western models of "smart bombs." However, the slow pace of delivering these weapons and the limited quantities pushed the defence industry to seek its own alternative solutions.

"We have the same high-explosive bombs as the Russians, left over from Soviet times. It's been 30 years, and we need to carefully examine what else can be used and in what condition the bombs are. We need to refine the elements that can still be used," explains Kryvolap.

Experts cannot estimate the exact number of these Soviet high-explosive bombs in Ukraine. Firstly, this figure is obviously classified. Secondly, it is worth mentioning the series of explosions at ammunition storage points in Ukraine over the last 15 years. It is difficult to assess exactly how many air bombs have exploded there.

In turn, Khrapchynskyi is confident that Ukraine should not only assess the quality of old Soviet air bombs but also contemplate using Western models as well as producing new ones.

"In theory, this could also be a new filling. Bomb production, although quite risky, is essentially very simple," asserts Kryvolap.

Brigadier General Serhii Holubtsov, chief of aircraft of the Air Force Command of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, noted in an interview to Donbas.Realities, a Donbas-related project by Radio Liberty, the lengthy work on domestic modules for guided bombs is associated with engineers needing to choose wing shapes, fine-tune the guidance system, and develop countermeasures to Russian electronic warfare systems.

The last point is noteworthy. Essentially, it is necessary to create an analogue of the mentioned Russian Kometa-M system, which poses a significant challenge for Ukrainian electronic warfare systems.

"Thanks to our engineers, we will create a much more advanced version than their Kometa-M, believe me," states Anatolii Khrapchynskyi.

The clear objective is to avoid malfunctions in the control and fixation modules of the ammunition on the aircraft's body. This issue often occurs with Russian aircraft, leading to the premature release of ammunition.

In particular, due to this issue, Russian aircraft in the spring of 2024 uncontrollably dropped at least 75 air bombs on the territory of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, and temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

Another issue is the carrier aircraft that Ukrainian guided bombs will work with, especially considering the potential introduction of American F-16s or even Swedish Gripens or French Mirage-2000s.

"I think the module itself should be aimed at NATO standards," believes Anatolii Khrapchynskyi.

Even if the modules are designed more for Western aircraft types, which Ukraine plans to switch to in the future, the current fleet is sufficiently adapted, demonstrating the use of Western armaments on MiG and Su jets.

The number of guided bombs Ukraine plans to produce is currently unknown, but it's evident that achieving parity with Russian volumes is unlikely. However, experts emphasise that quantity is not the determining factor.

"If we achieve high precision, we won't need 3,000 guided bombs that hit anywhere. We don't need a wall of fire like Russia is resorting to. The more accurate the weapon is, the fewer explosives are needed to hit the target," says Kryvolap.

Khrapchynskyi is also confident that Ukraine will not employ the Russian tactic of chaotic bombing strikes but will focus exclusively on strategic military targets. For this purpose, thousands of air bombs are unnecessary.

Ways to counter guided bombs

Most Russian guided bombs are difficult targets to shoot down. Such air bombs lack engines, so they do not leave a heat trace that can be promptly detected. The flight time of the projectile is also quite short (three to seven minutes), which does not allow for the timely deployment of any countermeasures.

Therefore, the only way to combat them is to down the aircraft carrying guided bombs or create conditions that make their entry into the drop zone too risky.

For these reasons, the Ukrainian government constantly reminds Western partners of the need to increase supplies of Patriot and SAMP-T air defence systems. The maximum range of these systems is up to 80-100 km (in some cases up to 150-160 km).

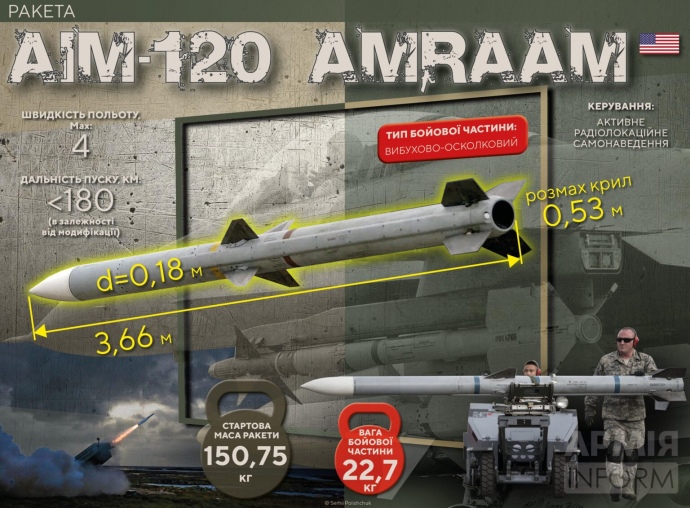

Another option is fourth-generation multi-purpose fighter jets. In our case, of course, we are talking about the F-16s, whose debut has long been awaited in Ukraine. If the aircraft are equipped with air-to-air missiles, most often referring to the AIM-120 AMRAAM with a range of up to 180 km in the latest version, the Russians will be less likely to risk their aircraft.

The arrival of the F-16 is not a panacea, and Russia is unlikely to abandon guided bomb attacks. However, with their presence in Ukraine, the Russians will have to consider a lot of additional factors, so they will have to move from "deadly walks" to carefully planned special operations, reducing the intensity of bombings.

The conditions for using Ukrainian guided bombs, even with the prospect of the F-16s arrival, are unlikely to differ significantly from the Russian ones.

"The situation will be symmetrical for both sides. First, distracting the air defence systems, then artillery training against the air defence systems, finding gaps, flying into them so that missiles cannot reach you and dropping bombs," emphasises Kostiantyn Kryvolap.

***

Statistics from the last month indicate that Ukraine has been increasingly successful in striking Russian air defence systems such as the S-300 and S-400, especially in Crimea. This has forced Russia to move its expensive anti-aircraft systems further and further, creating potential air corridors for attacks.

Whether this is a precursor to a wider use of Ukrainian missiles and air bombs is difficult to assess at this time. However, the task of "clearing the way" for air assets seems to have been taken up.

Yevhen Buderatskyi, UP

Translation: Sofiia Kohut and Violetta Yurkiv

Editing: Anastasiia Kolesnykova