"People called our withdrawal from Azovstal 'evacuation'. I was 'evacuated' to a Russian prison for two years." A 23-year-old soldier freed from Russian captivity tells his story

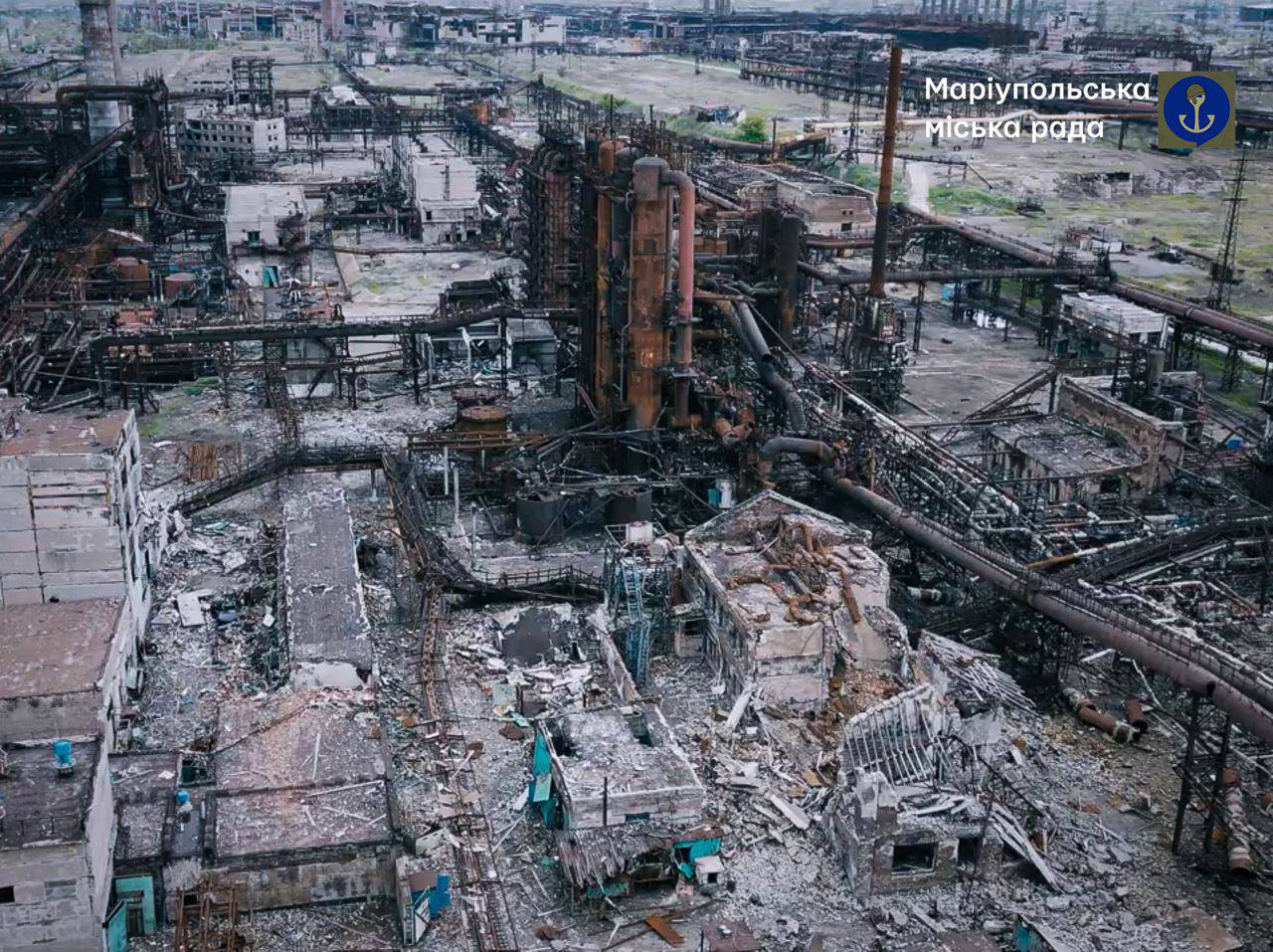

On 15 May 2022, fighting and shelling ceased at the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works in Mariupol, which was encircled by Russian forces.

The next day, Ukrainian soldiers started to exit the plant on the orders of the country’s top military and political leadership. Their so-called "evacuation" lasted four days. On 20 May, the last Ukrainian soldier left Azovstal.

The Ukrainian government referred to the Ukrainian forces’ exit from Azovstal as "evacuation". The UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross served as guarantors that all Ukrainian soldiers would be able to return to Ukraine in a prisoner exchange.

The Ukrainian government and international organisations promised that Ukrainian soldiers would be brought back to Ukraine from Russian captivity within three to four months. Since then, however, two years have passed, and yet data from the Association of the Families of Azovstal Defenders suggests that more than 1,600 Ukrainian soldiers who defended the steelworks remain imprisoned in Russia.

"When I was leaving the plant, I thought, ‘Thank God I’m alive’. Surviving there was almost impossible, especially when you were on combat missions," a soldier with the callsign Tarpan tells Ukrainska Pravda. At his request, we are not publishing his name.

"We believed that we would be freed within three to four months. We thought we could last that long", he says.

Tarpan is 23. Before the beginning of the full-scale invasion, he was a contract soldier and served in Mariupol. He joined the city’s defence in February 2022 and spent nearly two years in Russian captivity following the Ukrainian forces’ withdrawal from Azovstal.

Tarpan told Ukrainska Pravda about his hellish time at the Azovstal plant, Russian captivity, and his return to Ukraine.

The story that follows is in his own words.

I was born again on 9 May 2022 at Azovstal

I was deployed to Azovstal in March 2022.

At first, our unit supplied ammunition and other things to combat brigades. Under constant shelling, we brought weapons, munitions, and generator fuel to soldiers based in different parts of the plant. We’d mostly do it at night, so the Russians couldn’t so easily target us.

Later on, we started taking part in combat operations that were taking place at the plant. We were all-rounder soldiers: we fought, but we also still had to carry things around. We had no choice.

The Katsaps [a derogatory Ukrainian term for the Russians] amassed a lot of forces on the Mariupol front. They wanted to encircle and kill us at Azovstal. Fighters from the Azov Regiment, Marines, and other Ukrainian soldiers, all in one location – they thought it was a real gift. They deployed every weapon they had against us: air-dropped bombs, phosphorus munitions, tanks, aircraft, mortars.

They also deployed thermobaric weapons that literally make your body evaporate. After one of these thermobaric attacks on an Azovstal bunker, we had to pick up parts of a soldier’s body scattered across the site of the attack and put them in plastic bags. He was at the epicentre of the attack. We only recognised him by his load-bearing vest. He was a good guy.

The Russians even used drones to scatter mustard gas over our positions. It might seem innocent at first, but inhaling it damages your internal organs.

The plant was relentlessly shelled. Moving around was extremely dangerous. During one of our sorties, the Russians started firing mortar bombs at us. Two brothers-in-arms and I decided to wait it out in a small building at the plant. As soon as we entered it, the Russians started attacking it, too. We barely survived.

At Azovstal, I thought that some form of higher powers must exist. Whatever you prepared for would happen. When it was my turn to go on duty at the positions, I tried to convince myself that everything would be alright, because it can’t not be – I had family waiting for me at home. When others decided that things wouldn’t go well for them, that was usually what happened.

I remember once, before a sortie, a brother-in-arms who was also going told us: "Guys, we’re f**ked. We’ll never come back from there". I was 21 at the time, and I really didn’t want to die. I thought to myself: "Thanks, Vova, for the encouragement", but I still tried to remain positive. I managed to survive that time, but Vova didn’t.

During combat sorties, I feared losing limbs more than I feared death, because there were hardly any medicines left.

Soldiers who have had their legs or arms blown off were dying from pain. There were no analgesics, they’d just get novocaine injections. F**k, they’re dying, and you’re injecting them with novocaine?! It’s not just medicine that was in short supply – there weren’t any bandages, and medics had to use any old rag to bandage people’s wounds.

Ukrainian helicopters brought us food, medicine, munitions, and Starlink satellites a few times. It wasn’t enough, but it was something. They evacuated soldiers with the most critical injuries on their return journeys.

Later, however, the Russians started shooting our helicopters down, and we had no more deliveries.

There was hardly any food at the plant, but we only had one goal – to survive – and adrenaline made us quite inventive. We improvised stoves by soaking wads of cotton in antiseptic, placing them over wires, and setting them on fire. That way, we could boil water to make tea or cook something. That’s what we used for most of our cooking: we made porridge, soup, bread, coffee and tea.

By the way, I cooked my first borshch at Azovstal. It was the best borshch I’ve ever eaten, with canned meat and beans. I will never forget how it tasted.

We made very simple bread by mixing flour, water and salt, and frying the dough in a frying pan.

The lack of water was our main issue. We quickly used up all the stockpiles we had, so we had to drink rusty water we drained from radiators. We used the same water to wash ourselves and our clothes, but that was rare.

Once I washed my spare uniform and hung it up to dry before going on duty. I was so excited I would get to wear clean clothes again. But the building where I hung my uniform was hit by a missile, which also killed several of my brothers-in-arms.

Death kept chasing me. I was born again on 9 May 2022. At 02:06 that night, a missile hit the basement where I was resting with a group of other guys. A fire broke out and several concrete blocks collapsed. Everyone was running around screaming – we carried many dead and wounded soldiers out of that basement.

By the way, just before we came out of the plant, [Russian] f**kers started attacking the bunkers and basements we used as our hiding places.

We were told to leave the plant on 15 May. The Russians clamped down on the plant, leaving us little breathing room. We hardly had any weapons or ammunition. Only small guns. No artillery and hardly any equipment. We couldn’t break through.

The last time I talked to my family was on 17 May. I left the plant on the 18th. We were not allowed to say we were surrendering. Our commanders referred to this as "evacuation". F**king hell, I was "evacuated" to a Russian prison for two years.

"You don't need a calendar in captivity"

I was brought to Olenivka at first. The soldiers who had been captured earlier told me that at first there were supervisors from the "Donetsk People’s Republic" in the Olenivka colony ["DPR" is a self-proclaimed and non-internationally-recognised quasi-state formation in Donetsk Oblast]. They were preparing hellish conditions for the Azov fighters, whom they considered the embodiment of all evil. But shortly before our arrival, the "DPR" wardens were replaced by the Russians for some reason.

The vicious Russians took everything I had with me – a jacket, waterproof raincoats, a fleece jacket, a military shirt, a briefcase and documents. By the way, my passport and driving licence were returned to me after the prisoner swap. They also gave me two small icons with prayers, one of which read "Lord, oh Great and Almighty, protect our beloved Ukraine!" To be honest, I was shocked.

The conditions in Olenivka were terrible. We slept on rotten mattresses. We were hardly fed – two scoops of water with a few pieces of potato, which they called soup, and a few pieces of dry bread a day.

They gave us almost no water. Sometimes a fire truck would come and throw out a hose of marsh water with algae: you could drink what you scooped up. If you don't want to, then don't drink it. We had to take at least a few sips to avoid dying.

They took me out of Olenivka before the terrorist attack. The wardens came in, called our names and said: "Line up in a row. You have five minutes to get ready." I was happy. I thought there would be a prisoner swap.

But I was transferred to a Russian barrack-type colony. At first, we were interrogated. One of the questions they asked everyone was whether a person had communicated with civilians at Azovstal. If someone said that they had, or that they had helped or shared water, food and medicine, the f**kers wrote down that that person had illegally kept people in the bunker, beaten, tortured and raped them. The attitude towards such fighters was, to put it mildly, appalling.

The Russians called us all sorts of names: "antichrists", "Ukrainian thugs", "Banderites", "Nazis" and "fascists".

The worst part is that they actually believe it. They have crazy propaganda running 24/7. There was a TV in our barracks. We had to watch propaganda TV channels to know at least something about Ukraine. Most often, they showed programmes by the insane Skabeeva [the TV presenter and political commentator, Olga Skabeeva].

Russian "journalists" are spouting lies around the clock, saying that Russia is a "great country that will defeat everyone", that they have "the best air defence" and "the best aircraft". They also say that the Russians kill 1,500 of our soldiers a day. They believe this without even realising that if it were true, there would be no people left in Ukraine.

It was very hard to watch their lying TV programmes. Two years in isolation. You have no access to reliable information. You just listen to the Russians justifying their crimes and telling you what "good people" they are.

The food in this colony was better than in Olenivka. They even gave us potatoes and pasta. We only dreamed of a treat like sweets. I wanted biscuits and condensed milk the most, and my friend kept mentioning the Kyiv cake. He said that as soon as he came back from captivity, he would eat the whole cake in one go. This guy was liberated at the same time as me.

We drank dirty water, scooped from rusty tanks. There were separate tanks for bathing and washing. Hygiene products, such as soap, toothpaste and washing powder, were scarce. I just wanted to wash my face properly, brush my teeth, wash my clothes, and put on a clean uniform.

On the positive side, if there was one, there was a chapel on the colony's premises. We prayed there and could also read books. I read a lot of literature about nature and travel. It helped me to switch off the negative environment.

The time in captivity was insidiously dragging on. I watched the clock but never followed the dates. We didn't have a calendar. And you don’t need a calendar in captivity. Why worry once again about losing years of your life in a Russian colony?

"People got on the bus and I heard the words I'd dreamt of: 'Good evening, guys. You are in Ukraine.' It was just incredible"

One winter’s day, the guards flew into the barracks and read out a list of names, including mine. They took us outside and put us in cold Ural [a Russian company making armoured vehicles] cars. No one told us where we were going. They pulled hats over our eyes and wrapped them with scotch tape. They tied our hands with scotch tape as well.

We were transported for more than a day. At first, we were travelling by Ural; then we got on a plane. I don't know where we arrived, but there we were loaded into vans, in which we were driven almost to the final destination. Just before the prisoner swap, the Russians transferred us to warm buses to put on a show.

All this time our eyes were covered and we couldn’t see anything. It was a terrible experience – you can go crazy like that. It was also very cold. We were not given water or food. They did not let us go to the toilet either.

After about a day, they cut the tape on our hands and told us to take off our hats and jackets. They were so petty that they even took away our old and terrible peacoats, which had less polyester wadding than the brushwood in bird nests.

After that, we drove a little further. Then we stopped. The Russians offered us the chance to stay on their side. Of course, we all refused. Then they said that they would not take us prisoner a second time, and they would shoot us immediately.

And then the lights came on.

People entered the bus, and I heard the words I’d dreamt of: "Good evening, guys. You are in Ukraine." It was just incredible. Unforgettable words. They gave us Ukrainian flags. We wrapped ourselves in them. It was an absolute thrill! It is impossible to convey those emotions in words.

Kyrylo Budanov was among those who met us during the prisoner swap. It was very encouraging. Because the Russians "killed" him almost every time when they hit Kyiv with missiles, as they claimed in their news.

And people met us with flags, torches and posters. We were travelling, and we understood that Ukrainians were waiting for us prisoners of war. This was very important and pleasant.

We immediately went to the rehabilitation centre, where we were finally able to bathe properly, change clothes, eat, and call our relatives. The last was the most frightening. I didn't know what had happened to them in these two years.

As it turned out, when I was captured, dad had immediately joined the army. He was wounded on the Bakhmut front and later died in hospital. I last saw him at the end of 2021. He and my mother saw me off to the service in Mariupol. I could not even imagine then that it would be the last time I would see him.

My dog died. He was very smart. We had a special connection. My family said that he began to miss me when I got to Azovstal. In the end, he could not stand it and died.

After coming back to Ukraine, I began to appreciate ordinary things that I hadn't even noticed before – moments with loved ones, blossoming trees, singing birds and a starry sky.

In captivity, there was no opportunity to enjoy regular things. There was nothing there except high concrete walls. If a bird managed to fly past the barbed wire, everyone was thrilled.

Now I feel real freedom. It is not for nothing that our anthem says, "We will give our soul and body for our freedom". Without freedom, things are unimaginably difficult. It should be valued and fought for. And so I will go back to the front soon.

Anhelina Strashkulych, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Olya Loza and Myroslava Zavadska

Editing: Shoël Stadlen