"I saw something no one else has ever seen. I saw the inside of an explosion": Stories of Ukrainian soldiers who lost limbs and received prosthetics in the US

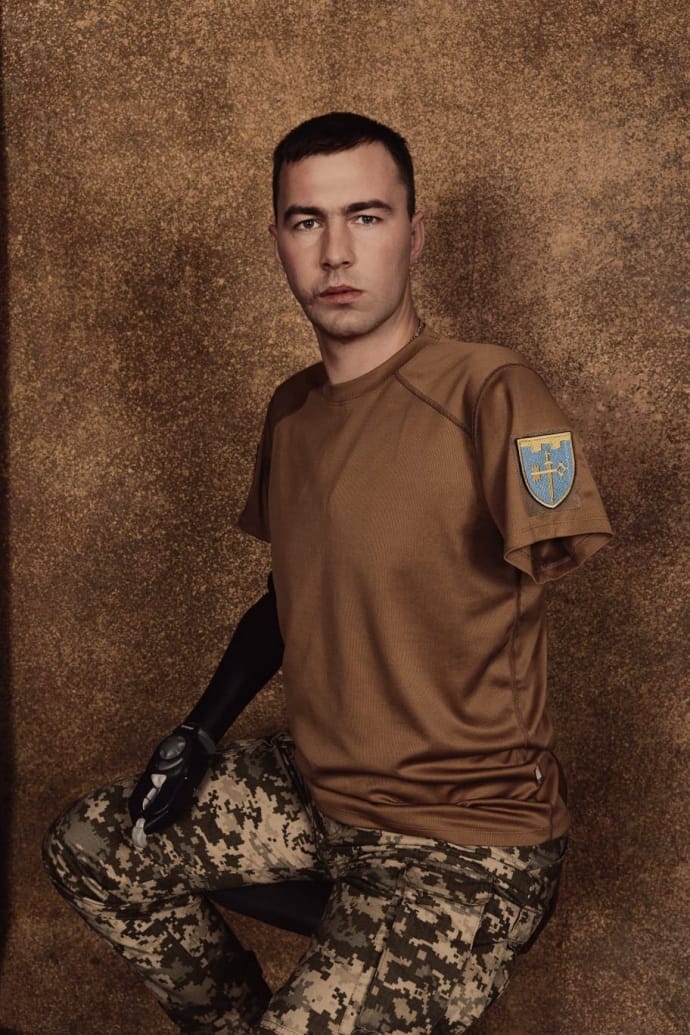

Yurii, Oleksandr and Pavlo are all Ukrainian soldiers. Oleksandr was mobilised in 2015 for a year. After a few months readjusting to civilian life, he decided to stay with the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the intelligence service. When the full-scale war started in February 2022, he was just waiting for orders.

Yurii served for 18 months in 2017, then returned to civil life, got married and became a dad. He returned to serve in February 2022.

Pavlo worked under contract as a tank crew member for the first tank brigade from 2020 to 2021. His contract ended in December 2021, a few months before the full-scale war. He’d promised himself that he’d never go back to service, but the sense of duty he felt towards his family and his comrades in service was stronger than his promises. He too returned to the military in February 2022.

None of these men were born ready for war, but they stepped up to defend their homeland for the sake of their families and their children’s future. Wounded on the battlefield, they are now trying to rebuild their lives. These three Ukrainian defenders tell their stories below.

"There are two options: either serve, or wait for the enemy to come and burn your house down"

Oleksandr (name changed for security reasons) jokes that his "business" in the army started in 2015. It was the fourth wave of mobilisation. After completing his term and returning to civilian life, he realised that he wanted to continue serving. He returned to military service and has never regretted that decision. Oleksandr explains what motivated him to do this.

"Many of my friends either served or were killed. So there were two options: either serve, or wait for the Russians to come and burn your house down. You're faced with a choice: either confront the war and halt its advance elsewhere, or wait for it to arrive at your doorstep, wrecking everything in its path. The 'house' is a metaphor; for each of us, it represents our loved ones, family, relatives and acquaintances – those we cherish more than our own wellbeing and even our lives."

Oleksandr said he believes that stopping the enemy far away from families and the familiar way of life might prevent the enemy from advancing any further.

Pavlo Nesterenko is from Kherson. Like most people, he worked, earned money for his family, and built a home for them. All that was before he served in the army. He joined the service under contract from 2020 to December 2021. When his contract came to an end, he promised himself that it would never ever happen again. But two months later, the full-scale war against Ukraine began.

"To start with, I brushed it off as a joke. I mean, it's the 21st century: we're sending people into space, contemplating colonising other planets, and amidst all this progress, war just feels inconsequential in the grand scheme of things," Pavlo says.

Pavlo firmly believes that just leaving and abandoning his home wasn’t an option. He stands firm, emphasising the importance of safeguarding everything he has toiled for.

"I’m not going to give up what I've earned through hard work," he says resolutely. "I won't surrender what I've built with my sweat and blood. I won't be driven away." Yet, beyond defending his possessions, there's a sense of duty and honour ingrained in him, a code he would never forsake.

He reflects, "If I hadn't returned to the war, I would have faced my children asking, 'Dad, why did you leave us to let these invaders take over?' I wouldn't have had the strength or conscience to face my loved ones later."

Yurii Trokhymenko hails from Zhytomyr Oblast and previously worked at Zhytomyroblenergo, the regional power company. He enlisted in the military in 2017. After a year of fixed-term service followed by six months under contract, he got married and moved to Ternopil in Ukraine’s west, working as an engineer until February 2022.

"My engineering job could've exempted me from going back to service," he ponders, "but I couldn't comprehend making any other choice – and I still can't. If I could turn back time, I'd make the same decision. I have a family, a wife, and this is our homeland. How could I not defend it? How could it be any different?"

"I realised that the time would come and everyone would have to serve. And as long as there are motivated people, it’s better to go to the battlefield. Because when it’s forced, it’s not good. It’s worse with those people. They have no values, and I was afraid of getting into a situation like that," Yurii adds.

"You are a warrior depending on the tasks you carried out and who you fought against"

Oleksandr is modest when he speaks about February 2022. He mentions that right up until 24 February, they were still waiting for orders regarding their deployment. Initially, Oleksandr defended nearby Kyiv from the Russians. Subsequently, he took part in operations in Chernihiv Oblast, Sumy Oblast, and Donbas. Throughout the autumn of 2022, he fought in the vicinity of Bakhmut. In September, following a period of leave, he was deployed to the Kherson front, where he was wounded.

"In sport, there's this idea that your prowess as an athlete is measured by the opponents you defeat. Similarly, in the army, there's this notion that your status as a warrior is determined by the adversaries you faced and fought against."

Yurii went voluntarily to the military enlistment office on 26 February. "There were a lot of people there. We were told not to queue up, and the very next day, at 2 o'clock in the afternoon, they took us on."

Yurii initially served in the Ternopil Territorial Defence, but then the brigade was disbanded and transferred to different areas. Yurii was on the border of Donetsk and Kharkiv oblasts when he was wounded.

Pavlo Nesterenko had already served as a tank driver, so he knew his responsibility already. Initially he went to Chernihiv Oblast in northern Ukraine.

"We didn't have a tank those first weeks. I was a tank driver without a tank till my colleagues brought one they’d taken off the Russians. We spent a long time repairing it because it was so crappy when it arrived, I don't know how you could have fought on it," Pavlo jokes.

In the spring, Pavlo’s brigade was split up and he went to defend Donbas, where after six months of fighting, he was wounded in the village of Pershotravneve. "Fighting isn’t scary, dying isn’t scary, pain passes. Being crippled is not cool!" Pavlo says.

"I saw the inside of an explosion"

A month of nightmares followed. Oleksandr drifted in and out of consciousness. His arms, legs and eyes required extensive treatment. In the spring, he travelled to the US, where he has been receiving treatment for eight months through the assistance of the Revived Soldiers Ukraine foundation. He’s made significant progress during that time, doctors say.

"You learn to walk and see again, you learn to operate with prostheses. Put it this way – the rise of the machines is happening every day, like in Terminator. All the prosthetics constantly pinch you in some way. First it felt peculiar, then quite interesting, but now it's just tedious. But a person can get used to anything. This is my job, and these injuries are professional," Oleksandr says, thanking the volunteers who are taking care of servicemen here in the US.

Pavlo Nesterenko was injured by a landmine that flew in when his combat vehicle was destroyed by a phosphorus bomb.

"From that point on, my veteran journey began. It's a long process, and without my wife's support I might have given up altogether, just stayed hunched over – it would've seemed easier that way. Being disabled and trying to get anything out of the government is incredibly challenging. Even being discharged from the Armed Forces is difficult. It’s hard to get in there, and it’s even harder to get out of there."

Pavlo lost his vision and his arm was amputated. "The doctors in Ukraine said they’d done all they could and told me to get used to the darkness. ‘Here's a cane for you – we'll give you a dog if you need one’."

The doctors did mention a method of treatment in the US – an experimental one, but it is available. Pavlo and his wife did their research and tried to get him to Philadelphia or Boston for treatment. Doctors in the US are trying to help him regain his vision.

Yurii Trokhymenko says that throughout his period of service, he and his comrades always tried to stay in shape. "Destiny has brought me into contact with some really cool, smart people. To prevent our bodies from weakening, we applied logic, did some tests and realised what our bodies were lacking. We did our best to take vitamins, fats and all these medicines so we’d be in good shape."

"I heard Russian being spoken and realised it was our enemies, because everyone in our brigade speaks Ukrainian. We heard Russian and realised they were Muscovites. The battle began. They fired at us for two days," Yurii says.

Yurii and his comrade took up positions on 23 March. "The Russians were aware of our movements and closed in on us. We were in very close proximity. We could hear their commanders issuing orders. They initiated mortar fire on us. Grenades were going off only a metre away, yet by some miracle, no damage was done. It made a racket, but there were no casualties, no injuries. That's how God's fortune favoured us," Yurii says.

Then an explosion occurred just as they were about to leave the position.

At the time of the explosion, Yurii's hands were still intact, and his face and jaw were undamaged. Despite this, Yurii kept on asking for tourniquets for his arms. While they were being evacuated, an enemy drone spotted them and resumed the attack. Yurii’s comrades had taken a huge risk in choosing to evacuate him. Amidst the bombardment, they carried him for nearly three kilometres across the bog to the evacuation vehicle. Yurii remained conscious throughout this ordeal, inquiring about the time and asking for tourniquets for his arms, realising how important they were. He lost consciousness in the evacuation vehicle.

"I left a part of myself in Ukraine. Literally"

Oleksandr plans to return to service to be as useful as he can. He jokes that he’ll be peeling potatoes. "I left a part of myself in Ukraine. One thing everyone should remember is that sooner or later we will face a worthy enemy on the battlefield. It’s wrong to think the Russian military is a piece of shit on a stick. Yes, there are plenty of fools, but there are also professionals who must be respected. Don't underestimate your enemy!"

Pavel has a large Ukrainian coat of arms tattooed on the back of his head. Soldiers believe the Ukrainian coat of arms or some other symbol of Ukraine can save them from being captured.

"When we’d just been transferred to Donbas and I was given seven days’ leave, I went to Kyiv and got the coat of arms on the back of my head. Ukrainian symbolism is a kind of protection against capture, because with symbols, you’re killed instantly. Even on the battlefield, when we saw the bodies, it was clear that the enemy was shooting where there were symbols. They say this is Nazism, but if being a Nazi is protecting your land, then OK, I’m a Nazi too then," says Pavlo.

"My prostheses are like a crane," Yurii says. "When I need to lift something, I think like a crane operator. I don't have an elbow, so I can't do everything quickly and habitually, but sometimes I imagine having a crane that gives me balance."

Yurii often faces the challenge of civilians not knowing how to interact with military personnel, especially when they are wounded. "It's important to remember that we're just regular people; we aren't limited, we just have different needs," he says. He adds humorously that the way technology is advancing, perhaps they'll all resemble Terminators in ten years’ time.

"I believe in God, and God guides me. Everyone helped me along the way, but you have to realise that this help comes gradually, not all at once. I’m grateful for the people who helped me. The last thing I want to say is: don’t expect everything at once. Each person gives you something, little by little, and it really does happen that way. That’s what I think to myself when I reflect on my journey."

Editing: Teresa Pearce