Sea drones, Elon Musk, and high-precision missiles: How Ukraine dominates in the Black Sea

On the night of 16–17 September 2022, a group of sea drones – the first of its kind in the global history of war – approached Sevastopol in Russian-occupied Crimea.

Head of the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) Vasyl Maliuk and Vice Admiral Oleksii Neizhpapa, Commander of the Ukrainian Navy, watched closely, monitoring the drones’ progress from a secure bunker. They were joined by Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov and a Brigadier General of the SSU’s counterintelligence wing with the alias Hunter, the man behind Ukraine’s sea drone program.

The team’s mission: to send the drones into the heart of the Russian Black Sea fleet – the Bay of Sevastopol – in hope of striking Russian missile-carrying ships.

"Those were the early models of those munitions. Some of them sank in the sea or spontaneously detonated. At the time the design was still rather flawed," Hunter told Ukrainska Pravda.

Still, five drones – each carrying 108 kilograms of TNT – had managed to make it, and were rapidly approaching Sevastopol.

"We were 70 kilometres away from the Admiral Makarov frigate. Everyone was tense, anticipating our attack. And then boom – we had our communications cut off. Elon Musk disabled Starlink satellites we were using to control the drones," a member of the team overseeing the operation told Ukrainska Pravda.

The target that the Ukrainian sea drones sought was only an hour – at most an hour and a half – away, but Musk’s decision threatened to undermine the entire operation.

"Fedorov tried to talk him out of it, but Musk wouldn’t listen. Other people were also trying to figure things out via their own channels of communication, but US [officials] said Musk’s firm was private, so they couldn’t put pressure on it," one of the people present in the bunker that night recalled.

The team tried to turn the drones around and bring them back to the base, but only two of them made it. The Admiral Makarov remained in Sevastopol, intact. But not for long.

"The two drones that made it back gathered invaluable intelligence on communications, navigation, the ship’s structure, and things like that. Ukraine’s Security Service and Navy set up a whole lab to study this information, taking it all into account, and enabling us to go back and attack Sevastopol within a month," a source told Ukrainska Pravda.

Ukraine’s first foray into the new, high-tech phase of the war for the Black Sea may not have been a success, but a year on, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy talked about his country’s two historic wins in 2023 during an end-of-year press conference: the start of accession negotiations with the European Union, and winning the battle for the Black Sea.

"Sometimes people fail to grasp and assess the importance of this operation. But everyone who knows about it in detail, both in Ukraine and internationally, speaks of it very highly. We have put an end to Russia’s dominance in Ukraine’s Black Sea," Zelenskyy explained.

Ukrainska Pravda found out the details of the pivotal naval operation, and is presenting an account of Ukraine’s biggest success in 2023 in this article.

No access to the sea: Russia’s efforts to blockade Ukraine

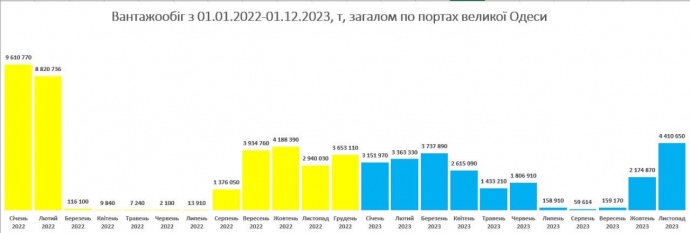

"Before the war, 60% of Ukraine’s total trade was carried out via the sea. We had 18 sea ports – 13 after Crimea was occupied. That’s a lot. This has enabled our metal, agricultural, and oil and lubricants industries to develop; they all relied on the sea [exports]. Halting sea [exports] has made Ukraine a totally different country," Deputy Infrastructure Ministry Yurii Vaskov explained, stressing the critical importance of free maritime trade for Ukraine.

"With the sea blockaded, we have to transport everything across the western border, which has an enormous impact on the economy. In the best case scenario, even if the border isn’t blocked, exporters break even. In most cases, however, they suffer substantial losses," Vaskov added.

Russia was fully aware of the importance of sea trade for Ukraine and started to gradually block Ukraine’s access to the Black Sea long before its full-scale invasion. Soon after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, it started putting pressure on trade ships entering the Azov Sea via the Kerch Strait. In autumn 2018, Ukrainian and Russian military ships clashed in the area after the Russian Federal Security Service damaged several Ukrainian vessels and imprisoned the crews of the Yany Kapu tugboat and the Berdiansk and Nikopol artillery boats.

Russia’s Navy began to expand its presence in northwestern areas of the Black Sea around mid-2021, undertaking a series of military exercises in the area. Moscow gradually narrowed the area Ukraine could use for trade.

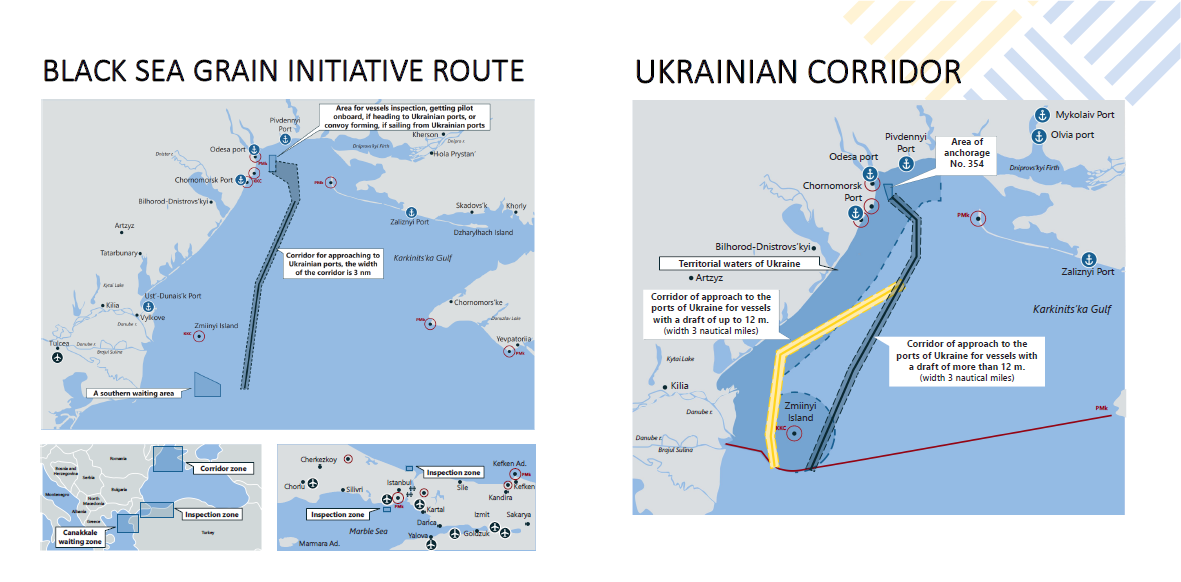

During the first hours of Russia’s full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022, Russian forces captured Zmiinyi (Snake) Island after sustained shelling and attacks.

Control of the island, situated 40 kilometres off the Ukrainian Black Sea coast, means total control of the naval traffic travelling into and out of Ukraine.

From early on in the invasion, Russian propagandists and Putin’s political henchmen openly admitted that two of the war’s main goals were to secure a land corridor for Russia to Transnistria and cut off Ukraine’s access to the sea.

However, by September 2022, when the first group of Ukrainian uncrewed surface vessels made an attempt to reach Sevastopol, Russia’s Black Sea ambitions had waned significantly in both scope and fervour.

From the very first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian Navy – armed with several Ukrainian-made Neptune missiles, determination, and resolve, but no large ships – started to shatter Russia’s dreams of Black Sea domination, one by one.

Although Ukraine’s first launch of Neptune missiles in late February 2022 was not particularly successful, the launch made it clear to Russia that it would be difficult to carry out naval landings in Ukraine. Naval landing operations were at the core of Russia’s strategy for occupying Mykolaiv and Odesa oblasts in southern Ukraine.

Ukraine made adjustments to the Neptune missiles after the unsuccessful initial launches. On 13 April 2022, the Neptune missile system achieved what had seemed unachievable: it sank the Moskva cruiser, flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet.

This historic event paved the way for the liberation of Zmiinyi (Snake) Island only two months later. On 30 June 2022, Ukrainian aircraft and Bohdana and Cesar self-propelled artillery systems forced Russia to extend its famous "gesture of goodwill" and withdraw its troops from the island.

"The Russians realised that they can’t come closer than 150 kilometres to the Ukrainian coast. They stayed at that distance, maintaining their presence in the Black Sea and in Crimea. We had to do something about it," Hunter stated in an interview with Ukrainska Pravda.

On 22 July 2022, military operations in the Black Sea came to a halt. The Black Sea Grain Initiative was signed into effect in Istanbul, Türkiye, enabling Ukrainian agricultural exports to leave Ukraine’s Black Sea ports.

The parties agreed not to obstruct ships carrying agricultural products or attack ports involved in the Grain Initiative, but the very day after signing the agreement, Russia launched a missile strike on a port in Odesa. From then on, Russia delayed each extension to the agreement and sabotaged the grain corridor’s operation.

[UPCLUB]

"The [Black Sea grain] corridor operated quite successfully and performed well until about February 2023. Then the Russians started using every means at their disposal to create artificial obstacles to its operation. From March onwards the corridor grew less and less efficient, with fewer and fewer ships being able to use it," Deputy Prime Minister Oleksandr Kubrakov, Ukraine’s signatory of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, said.

"It was clear that it would most likely be discontinued. But we made efforts, together with our partners, to maintain its operation – even at the most reduced level – until the very end to prevent Putin from being able to say that we broke the agreement or otherwise undermined it. In July, the Russians unilaterally withdrew from the agreement," Kubrakov added.

Everyone in Ukraine remembers 17 July 2023: that morning, Ukraine undertook its second attack on the Russian-built Crimean bridge, which connects Crimea to mainland Russia. For the first time, such an attack was carried out by the Security Service of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Navy’s unmanned surface vessels.

The operation was recently covered in the Crimean Bridge Encore: Security Service of Ukraine documentary, so there is no need to go into detail here, but it is worth noting that the strike on the bridge was not the first Ukrainian Black Sea operation that had devastating consequences for Russia.

The road to the events on 17 July had been paved earlier and wasn’t without its dramatic twists and turns.

A game changer: the evolution of uncrewed surface vessels

"President Zelenskyy has set a goal: to ensure Ukraine’s domination in the Black Sea. This is one of the main priorities for the Security Service of Ukraine. We particularly wanted to target missile carriers that [Russia] deployed to attack Ukrainian territory," Head of Ukraine’s Security Service Vasyl Maliuk explained.

Maliuk said that after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s Security Service set out to find ways of adapting to the new reality, and ended up with a rather creative solution.

"Our use of uncrewed surface vessels launched a new era in naval warfare strategy," Maliuk said, unable to disguise his satisfaction.

This new era started almost by accident, with a general known as Hunter arriving at a military training ground where aerial drones were being tested.

"I saw a Starlink terminal mounted on a drone – a large cargo drone, a ‘kolhospnyk’, as we call them. What did that enable us to do? Establish communication! We were able to control and transmit information over long distances," Hunter said.

"If this could be done with an aerial drone, why couldn’t we make a boat, load it with explosives, and use it to blow up Russian ships? That’d be a good way to drive them away. I went to Vasyl Vasylovych Maliuk, and that everything off," Hunter added.

But neither he, nor Maliuk, nor anyone else in the SSU had naval experience. In theory, they could make a drone, but without maritime knowledge they did not know the exact technical characteristics it would need to have, nor how it would be able to travel to its targets across the sea.

That was how Oleksii Neizhpapa, a commander in the Ukrainian Navy, came into the picture. He selected a small group of experts from among his subordinates to serve as an advisory group for the sea drone project.

The group’s two primary goals were to assist manufacturers and designers with their calculations and, more importantly, to train drone operators on how to operate at sea, including how to navigate storms and develop routes using old pilot maps, among other things.

It’s worth noting that the Navy serviceman who ordered the Neptune missiles to be launched at the Moskva cruiser in April 2022 was a member of this advisory team.

"We had an idea: we took an ordinary boat, installed an outboard motor, a simple thruster, and a Starlink on it, and started to race it around a reservoir. That was in June of 2022. We even tried to set up a repeater communication system, with several drones along the route serving as repeaters. We were looking for something to help us drive away Russian ships," Hunter told Ukrainska Pravda.

"We knew a drone couldn’t sink a large ship, but it could put it out of action for a substantial period of time, [damaging it enough] to necessitate lengthy repairs. By July we conducted the first serious test drives, with our surface vessels travelling some 200-300 kilometres. We had to press on," Hunter said.

The first drone squad was ready in September 2022, and a team of operators guided them to Sevastopol. However, Elon Musk's refusal to enable his Starlink satellites in Crimea caused the first mission to fail.

The team concluded that in order to prevent similar issues in the future, the drones had to have multiple communication channels. The most recent model of uncrewed surface vessels has three interconnected communication systems.

Russia began to deploy its Black Sea fleet to launch Kalibr missiles on Ukraine in the fall of 2022. Ukraine’s defence forces had to figure out a way to take down or damage Russian naval missile carriers.

On the night of 28–29 October 2022, all the pieces of the puzzle came together: the drones had been modified, the weather at sea was beautiful, the time was ripe to set sail for Crimea.

Four drones were sent directly to Sevastopol, while three others were directed south of the peninsula, where the Admiral Makarov – Russia’s newest frigate, flagship of the Black Sea Fleet after the sinking of the Moskva – floated on the roadstead.

The Admiral Makarov pushed through the sea at a moderate pace, not expecting an attack. One Ukrainian drone, settling on the right trajectory, collided with the right side of the frigate. The crew of the flagship, caught off guard by the attack, steered in a panic towards Sevastopolska Bay.

Two more drones pursued the ship, but with massive waves preventing them from making contact, they followed it to the coast. Half of the Marakov’s engines had been destroyed in the attack.

Just then, another group of Ukrainian drones managed to enter the Striletska Bay, but an attack was launched from the shore immediately. A massive spotlight flashed and Russian forces opened fire on the drones as they pushed into the bay.

Without warning, the Ivan Golubets, a Russian minesweeper, appeared on the navigation screen before a Ukrainian drone. The operators instantly received a command to take down the ship with 108 kilograms of explosives.

At that moment, other drones hit the oil station.

Unaware of what was happening, Russian coastal artillery fired volleys at its own flagship, the Marakov, as it rolled into Striletska Bay, until the ship fired a single reverse salvo to identify itself.

While the Russians fired at each other, the remaining drones broke into Sevastopolska Bay. The drones’ GPS signals vanished as the Russians turned on their electronic warfare stations, so there was little to no drone communication at that time. The direct optical channel aboard the drones was the only system that permitted navigation in any way.

"And here, Neizhpapa’s vice-admiral personally begins to control every metre of the passage of drones. He’s from Sevastopol himself, grew up there, served all his life, knows every bend of those bays. And one drone was taken to the Pivdenna Bay, the second to the Pivnichna Bay, the third to the Naftova Bay," said a member of the team who watched everything in the command bunker.

"This was the first ever remote naval operation. Uncrewed surface drones received their baptism of fire. But it was only then that we realised they had to be larger and carry more explosives for it to bring about an effective strike," said a member of the development team.

The cold autumn had just come, the drone season was ending, and the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) decided to overhaul its drone completely. It had to become faster, bigger, more powerful and carry an entirely different communication system.

With each new generation of these drones, the size of the warhead has been increased, progressively from 108 to 850 kilograms. Top-of-the-line communication systems are used, each costing more than US$300 thousand. The body is now made from radar-invisible material, and incorporates many other innovative solutions.

For example, the drones are now equipped with a flamethrower system that allows them to engage in naval combat in the true sense of the word. Ukrainska Pravda has footage of the first-ever battle between drones and coastal ships.

The video shows Ukrainian SSU's drones firing at Russian ships coming out of Crimean military ports to sink the drones. Instead of fleeing, the drones turn around and open fire in response.

The world knows this invention as SeaBaby. Little remains of the drone from its first iteration, except for its core idea and deployment tactics. It was the new SeaBaby that hit the Crimean bridge on 17 July 2023.

"Successful drone attacks have proved that this is one of the most effective ways to counter the enemy at sea. We’ve begun to scale the use of surface drones. Today, the SSU operates SeaBaby drones. These are new and more advanced generations of marine drones. No private companies are involved in this innovation. A team of SSU experts, engineers, IT specialists and sailors is working on it," said Vasyl Maliuk, Head of the Security Service of Ukraine.

The mention of private companies is not accidental. The first generation of drones was a private-public development. But when Maliuk and the team decided to make a new drone themselves, the company that was involved in the first project found a new customer: Ukraine's Defence Intelligence.

Kyrylo Budanov's department is the second in Ukraine to develop and operate a marine drone. Their project is called Magura.

The Magura drone is a 5.5-metre boat that can perform various functions, from observation to strikes. It has been involved in many operations to date, including a strike on the Russian Black Sea Fleet patrol ship Sergei Kotov in September 2023.

SeaBaby drones were also responsible for the destruction of the Russian corvette Samum, the Pavel Derzhavin patrol ship, the large rescue tug Nikolay Mura and, most recently, the reconnaissance and hydrographic ship Vladimir Kozitsky.

But even in recent months, the very philosophy of using marine drones has changed.

"We want to isolate the elements of a large warship – air defence, weapons, defences – and put those weapons on multiple drones," Hunter explains.

Ukraine does not have the time and money to build large warships, but an army of drones – air defence drones, kamikaze drones, drones with weapons – can solve the issue of the fleet in an entirely different way.

"SeaBaby is no longer just a naval drone, but a multipurpose platform that the SSU today actively uses for various tasks, including attacks on the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation," Maliuk added.

To put it simply, Ukrainian drones have evolved beyond just "kamikaze" drones – now most return back to their bases after a successful mission.

The New York Times recently cited Ukraine's Defence Intelligence, writing that drones are now also used for remote mining and other tasks.

News for Novorossiysk

The withdrawal of Russia from the grain initiative in July 2023 resulted in almost instant missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian ports. The entirety of Odesa Oblast was struck, from Chornomorsk to Vylkove and Reni.

Ukraine again found itself in a naval blockade. Though this time, it was different – Kyiv had foreseen such a scenario and a plan to break out the blockade was already in play.

In a July meeting attended by President Zelenskyy it was decided that Russia should firstly receive a military retaliation for attacks on Ukrainian port infrastructure. Secondly, Ukraine needed to send a clear signal that there is no place in the Black Sea where Russia’s ships are inaccessible to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

After that initial meeting, several follow-ups were held in the office of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Valerii Zaluzhnyi.

"There were Maliuk, Budanov, Neizhpapa, Kubrakov, and representatives from the Air Force. That was the first time in a long time that all those different departments had worked out a strategy, described plans and operations so coherently and without competition. Everything moved rapidly, and within a few weeks we reported to the president that we were ready to act," said a participant from the meetings.

Ensuring the operation of the new grain corridor and the driving away and destruction of Russian missile-carrying ships demanded a wide breadth of military experience and involvement.

To begin, Ukraine showed Russia the vulnerability of its own ports.

On the relatively quiet night of 3/4 August, another innovation of the SSU – the experimental drone Mamai – went to sea.

Mamai is a pure "kamikaze" drone and has a smaller warhead than SeaBaby – 450 kilograms. It is the fastest of Ukraine’s naval drones, allowing it to sail almost anywhere in the Black Sea. That night, the mission required just such capabilities – the port of Novorossiysk lay ahead.

It was after a wave of attacks by Ukrainian drones on Novorossiysk that a number of the ships of the Black Sea Fleet withdrew from Crimea. As well as being a military port, Novorossiysk is at the heart of Russian maritime trade.

The route to Novorossiysk is long. As the drones were steered over the Black Sea, their operators were constantly tempted to strike targets along the way.

"Somewhere en route the operators saw a tanker. They asked if it could be perceived as a target. No tankers! If we hit a tanker in neutral waters, then we’ll be branded as some kind of terrorists. Your target is the port. And there, you’ll see – maybe you’ll be lucky," a head of the mission said.

"And they were lucky. There’s a video where the operators in the bunker are shouting ‘here, look – it's definitely military, it's definitely a warship, let's strike!’ And well, they were overjoyed. They went to the port, and right there – a warship. Great luck!" the source adds.

The Mamai had hit the Russian landing ship Olenegorskiy Gornyak. Photos of the ship circulated around the world on 4 August. Ukraine had struck Russia at its most vulnerable point at sea.

A day later, the Mamai did make contact with a tanker, but this one an absolutely legitimate target: the Sig, a tanker directly involved in servicing the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation.

Ukraine had sent a message and Russia had received it. War can come to your ports too.

"It should be understood that any mishaps at sea are also disadvantageous for the Russians. They immediately lead to a rise in the price of insurance and freight. For global insurance companies, the entire Black Sea is one region. And if something happens in Odesa or Novorossiysk, the cost of insurance grows for the region as a whole," Yurii Vaskov, Deputy Minister of Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine, explains.

Ukrainian estimates indicate that the purely economic losses that Russia suffered from two attacks on Novorossiysk were in the hundreds of millions of US dollars.

But Russia wasn’t the only country to feel the losses. The port also plays host to major oil transshipment operations. It is through Novorossiysk that oil giants from the United States export Kazakh oil. It is from Novorossiysk that Russian oil is exported under the guise of other brands.

The game Ukraine played had high-stakes. According to Ukrainska Pravda, the country’s leadership received warnings from partners at all levels. But the game paid off. Russia was forced to let up its pressure, and on 10 August, Ukraine was able to declare its own temporary sea corridor, independent of Moscow.

We are our own corridor: the first ships to Odesa

The first vessel to leave the port of Odesa on the morning of 16 August was the Joseph Schulte, a container ship. The ship had been in Odesa since 23 February 2022.

Russia’s full-scale invasion caught many ships in Ukrainian ports. During the first grain corridor, all ships carrying agricultural products were able to leave Ukraine, but container ships and ships loaded with iron ore remained. These were the first vessels to use the new Ukrainian corridor.

"But we needed vessels that would come to Ukraine, not just from Ukraine. We worked with the market, saying that we would take on a little risk, but they would make a profit. And so the first vessel was found. It was an awesome and exciting moment," recalls one of UP’s sources in the transport field.

The ship has a telling name: Resilient Africa.

This vessel could be the subject of its own adventure film. Purchased by a Ukrainian agricultural company eager to lease a ship, but unable to find a willing lender, the new owners immediately renamed the ship. If Russia had sunk the Isabella or the Bort 423, it would have been ordinary news. But an attack on the Resilient Africa, with Putin masquerading as a friend of African countries, would have made a dramatic headline.

Apart from its symbolic value, the corridor's operation is vital for Ukraine. Normal operation of the corridor could, according to estimates, provide a 5-7% increase in Ukraine’s GDP just this year.

"We worked with shipowners, provided state support mechanisms and reduced insurance rates. And it worked: companies went to sea and through our corridor. We have now handled 10,600,000 tonnes of cargo since the route has been open. This is mostly exports, purely commercial cargo," explains Yurii Vaskov, Deputy Infrastructure Minister of Ukraine.

Obviously, Russia is not satisfied. Continual attacks with missiles and drones led to nearly 180 port infrastructure facilities being completely or partially destroyed at the end of 2023, Vaskov said.

Russia wouldn’t be Russia if it didn’t look for some new way to disrupt the normal operation of Ukraine’s corridor. Most recently, the Russian military has begun remotely mining the sea with guided aerial bombs.

From a safe distance, Russian bombers drop guided aerial bombs with special sensors into the shallowest parts of the corridor. These sensors trigger a detonation when a ship passes over them. It was in the act of mining that a Ukrainian air defence missile caught a Russian Su-24M bomber on 5 December near Zmiinyi (Snake) Island.

* * *

It is crucial to note that at this point Russia can only place mines in Ukraine’s Black Sea corridor if it deploys aircraft.

After the attack on Novorossiysk, the economic team led by Kubrakov separated from the military and the Security Service of Ukraine and set to work on establishing a naval trade route. The military, in the meantime, continued to pursue its other goal: the destruction of Russian missile launchers and the banishment of the Russian Black Sea Fleet from Crimea.

Ukrainian defence forces have made very significant progress toward this goal since August 2023.

Late summer, autumn and winter saw a series of successful operations that were largely enabled by the initial success of Ukraine’s sea drones. Russia lost the ability to move freely by sea and was forced to keep to Crimean ports.

This is where Ukraine is now deploying its new weapons and, crucially, implementing its unique tactics. Intelligence and reconnaissance work undertaken by Ukraine’s security services has meant that Kyiv is aware of every Russian ship entering Crimean ports.

Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, which is now building a new base in Abkhazia, may want to avoid Crimean ports, but only Sevastopol has the infrastructure to load Kalibr cruise missiles onto missile carriers, and only Crimean factories are capable of repairing large Russian Black Sea Fleet vessels. Russia has no choice but to use this infrastructure.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian defence forces now have the know-how to intercept and attack Russian ships at these vulnerable moments.

First, Ukraine deploys swarms of heavily armed, long-range drones that can reach the Crimean coast. Their task is to exhaust and destroy Russian air defence systems in a particular port at exactly the right moment.

After disabling Russian air defence systems, the Ukrainian Armed Forces deploy high-precision cruise missiles to hit dry docks, berths, and bays – wherever Russian ships are located.

This is how, to date, a dozen Russian ships and the Rostov-on-Don submarine have been destroyed.

Ukraine’s fight against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet began with drone attacks on Sevastopol, in the west of Crimea. But after Ukraine’s crushing attack on Kerch, Crimea’s most eastern point, on 4 November, when the Air Force damaged Russia’s state-of-the-art Askold missile carrier, Russia got the message: there is nowhere in Crimea for its Black Sea Fleet vessels to hide.

"We want to drive every Russian missile carrier from the Ukrainian Black Sea. And then we will turn our attention to submarines. The Security Service, the Navy and the Air Force are already preparing surprises for the occupiers. Russia has withdrawn all its major ships from Crimea, but that won’t help them. There is no room for the Russian Fleet in Crimea," said Vasyl Maliuk, Head of the Security Service of Ukraine.

The black crater at the site of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet headquarters, which was destroyed by Ukrainian missiles, is an omen of things to come.

Russian ships will be chased down and eliminated until the last vessel is in formation behind the Moskva, its sunken flagship.

Roman Romaniuk, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Olya Loza, Theodore Holmes, Sofiia Kohut and Myroslava Zavadska

Editing: Sam Harvey and Olya Loza