Reconstructing chronology of how Ukraine's Armed Forces prepared to defend the south, mined Chonhar and fought for Kherson Oblast

The defence of the south [of Ukraine] is one of those stories of the full-scale war that is shrouded in legend in the media and on social media. The accounts can be both positive and negative as regards the Ukrainian government and military.

Since April 2022, the State Bureau of Investigation, which reports to the Office of the President, has been conducting a criminal investigation into the events in Kherson Oblast [after the full-scale invasion]. Ukrainska Pravda has obtained information that this case concerns possible negligence by the military. Specifically, Operational Command Pivden (South), responsible for the Ukrainian forces in the south, is suspected of having failed to properly place mines at all facilities.

The investigation is ongoing, and the authorities and law enforcement agencies have not yet disclosed even partial results. This gives further room for speculation and political manipulation.

All this time, society heard nothing from the military units working directly in the field in Kherson Oblast.

Ukrainska Pravda decided to give them the floor.

For several months, we have been reconstructing the chronology of how the occupation of Kherson Oblast began, together with those who led the defence of the oblast and commanded the defence units, who on the morning of 24 February were supposed to hold off the Russian offensive and blow up the bridges in the village of Chonhar, who placed mines at all those bridges and checked the explosive devices.

Read more on the topic: Ukrainian marine tells his story of trying to blow up bridges in Chonhar on brink of Russian invasion

This is Ukrainska Pravda’s reconstruction of the events in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, drawing on the accounts of everyone we managed to talk to.

We explain how the defence of the south was prepared, how many troops were present on both the Ukrainian and the Russian sides, why the bridges to Chonhar were not blown up and what happened along the southern border on 24 February 2022.

For the first time, we are sharing a photo of one of the bridges that was blown up and a Russian map of the offensive. We also recount the story of a secret combat logbook that records all the mines in and around Chonhar.

***

Ukrainska Pravda asked the State Bureau of Investigation for official comment. Citing the secrecy of the investigation, they provided only very general information.

Currently, military and explosive enquiries are being carried out into the case, although investigators do not even have access to the scene. Operational Command Pivden (South) and unit commanders have been interrogated as witnesses.

Ukrainska Pravda’s sources in law enforcement agencies said that there was no evidence to suggest that there had been any demining; the main defendants in the proceedings may be Lieutenant General Serhii Naiev, the commander of the Joint Forces, and Major General Andrii Sokolov, the former commander of the Pivden (South) forces.

At the same time, one of the important witnesses, the soldier Ivan Sestryvatovskyi, who was supposed to blow up the bridges in Chonhar, was questioned by the State Bureau of Investigation only after an interview with Ukrainska Pravda had come out. Several other soldiers who blew up other bridges and survived have probably yet to be questioned.

How the defence of the south was planned and the mining

2015: Chonhar and the surrounding area are mined

Until the end of 2014, the Chonhar Isthmus, which connects Crimea with Kherson Oblast, was a "buffer" zone. For nine months, not only did it live under Russian occupation, but was in fact the crossroads between Russian and Ukrainian military vehicles.

The Russians retreated from there in December 2014. A few months later, there were reports that Ukraine was mining the bridges in Chonhar.

One of the representatives of the Joint Forces Command, a unit of which has been monitoring the mining for the past few years, told Ukrainska Pravda that after the Russians seized Crimea, Ukrainians did indeed set up professional explosive barriers on the border:

"Facilities were prepared for destruction – bridges and dams, and anti-tank fields were laid as well. There were also mixed groups: anti-tank and anti-infantry barriers."

And that was not just in the "infamous" Chonhar.

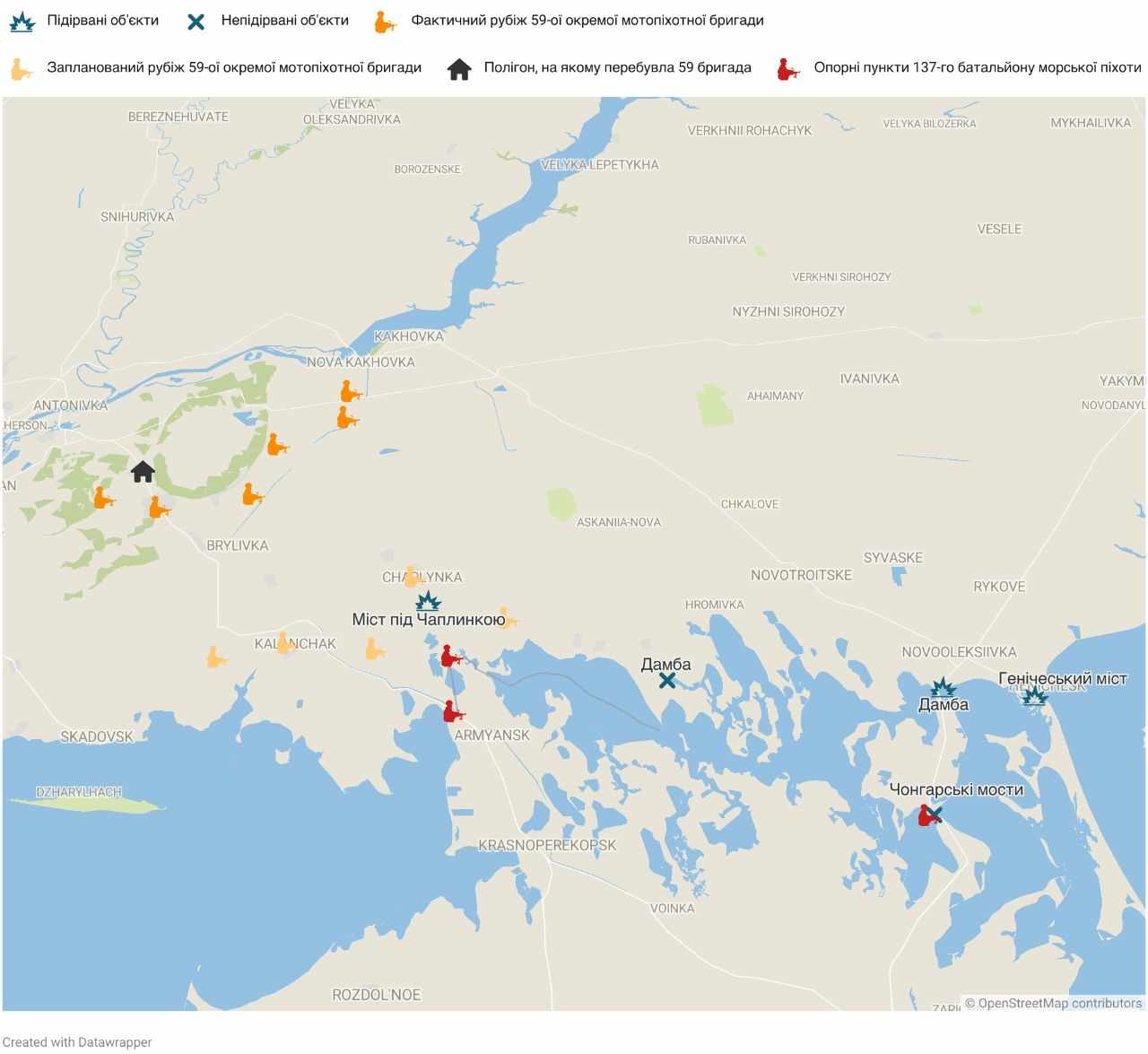

There are only three routes that lead from Crimea to mainland Ukraine. Two of them are land roads through the Kalanchak and Chaplynka checkpoints. The way to Kherson and Nova Kakhovka opens up from there. The third checkpoint is at Chonhar, which leads to Melitopol.

This particular access point could be mined, because it goes over a bridge. Explosives are generally placed under a bridge. At the same time, roads are normally protected by anti-tank mines, but these cannot be laid if a road is used by civilians, as was the case on the border with Crimea.

There are one railway and two road bridges on the Chonhar Isthmus. In addition to these, a bridge in Henichesk and four dams along the border with the peninsula were ready to be blown up.

The only bridges from which the mines were eventually removed are located further inland, on the North Crimean and Kakhovka main canals. They were demined before 2018, because the number of military personnel in the south was decreasing and there was no one to maintain these bridges.

"Over time, the number of troops decreased because they were needed in the ATO zone ["Anti-Terrorist Operation zone" was the term used from 2014 to 2018 by the media, the government of Ukraine and the OSCE to identify the zone in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts under the control of Russian military forces and pro-Russian separatists where combat actions were taking place – ed.]. You cannot leave a mined bridge on civilian territory unattended", says Andrii Sokolov, who was the commander of the region’s defence forces at the time.

The ammunition from those bridges was stored in storage points in Chaplynka until the full-scale invasion. That way, in the event of a threat, they could be prepared for detonation again.

The bridges were not the only obstacle for the Russians. The military set up minefields behind the bridges in places where vehicles could cross.

The sappers recollected that there were five such fields. The soldiers with whom Ukrainska Pravda spoke can still mark them on the map from memory.

It is important to consider that all these obstacles were placed on territory that did not have any special status before the full-scale war and was considered peaceful. The defenders could therefore not mine the gardens or fields of farmers as densely as they do now, during the full-scale war.

All the military personnel with whom Ukrainska Pravda spoke pointed out that no one removed mines from the bridges on the isthmus. Had that been done, traces would have remained in military reports and orders. The mines themselves were recorded in the official logbooks of the units that served on the border with Russia.

All devices and power grids were checked twice a month. In the first and third weeks of each month, sappers went to the Kherson front, and in the second and fourth weeks – to the Melitopol front.

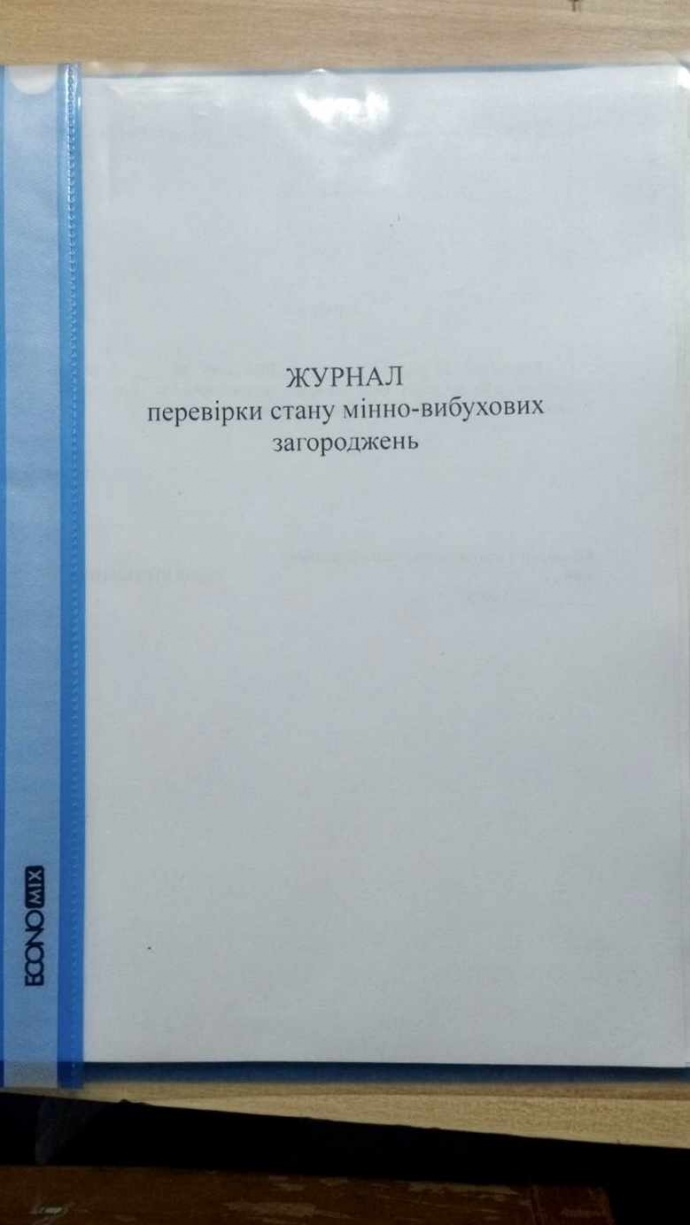

"In addition, there was an inspection logbook. For some reason, no one talks about this. The logbook has been preserved," recollects the head of the specialised unit in the Joint Forces Command.

The logbook he is talking about was kept by the 808th Separate Support Regiment. It records not only the dates of inspections, but those who conducted the inspections entered their names and signatures.

If the inspectors had seen any malfunctions, they would have recorded them in the logbook. The sappers who kept it said that there were no such cases.

A copy of this logbook, as Ukrainska Pravda was told, was handed over to the official investigation back in 2022.

Could the Russians have known where our obstacles were located?

The soldier smiles slightly in response to this question: "There were signs of the mines. There are locals who can still see those marks."

Spring and autumn 2021: Ukrainian Armed Forces renew mining operations

A year before the full-scale war, in February 2021, three soldiers were killed by an exploded mine in Donetsk Oblast. At that time, President Zelenskyy ordered that all road barriers, among other things, be checked and those that were outdated or no longer appropriate be removed.

This order applied only to the east of the country. But the troops decided on their own initiative to conduct the same checks in the south as well.

This verification coincided with the seasonal period of maintenance, when after winter, snow and flooding, all mines are checked especially carefully to make sure nothing is damp or damaged.

Orders were sent down from the Joint Forces Command to the south: barriers should be increased or removed, as needed. The response was as follows: nothing needed to be removed, only one group of anti-tank mines (17 pieces) had to be added. And they were installed.

In the autumn of 2021, sappers replaced the explosive component on every mine. This was the first time this had happened in the south.

"It was done once, but it was done on time," Ukrainska Pravda's source among the sappers summed up.

Autumn 2021: Structure and defence plan for the south take shape

Five months before the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian and foreign media had been trumpeting the threat of a Russian offensive. Kyrylo Budanov, Chief of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, stated publicly that the country's south might be one of the areas of invasion.

Ukraine's southern forces are not a permanent formation. Their military personnel are rotated regularly. This happened again in the autumn of 2021.

Two units exhausted by the war in Ukraine's east [war in Donbas beginning in 2014, a part of broader Russo-Ukrainian war – ed.] had been relocated to the border with Russian-occupied Crimea. These were the 59th Yakiv Handziuk Brigade and the 137th Marine Battalion, and would form the main force that would encounter the Russian offensive on 24 February.

Meanwhile, Major General Andrii Sokolov was appointed commander of the Southern forces in the autumn of 2021.

Sokolov had previously held that position in 2018-2019. Prior to that, he had served at the headquarters covering the areas connecting mainland Ukraine and Russian-occupied Crimea and also in the city of Kramatorsk. He spent two years leading the 72nd Separate Mechanised Brigade (known as the Black Zaporozhians), particularly near the city of Avdiivka in Donetsk Oblast.

"When I assumed the position of commander of this group of troops [in October 2021 – Ukrainska Pravda], I scheduled training from day one. Training exercises were planned with the 137th Battalion and to prepare the headquarters staff." Sokolov said he had been preparing his subordinates, regardless of whatever statements about the upcoming Russian offensive were made in the media.

The major general approved two action plans. A stabilisation operation, which lasted throughout peacetime, and a defensive one in case of escalation.

Sokolov explained that he was supposed to be assigned two brigades (3-5,000 people each) and a battalion (500 people) directly on the border with Crimea for peacetime. Should hostilities break out, this formation was supposed to be supplemented by two additional brigades of the Territorial Defence Forces (TDF).

However, in fact, the South lacked a comprehensive grouping of forces even in peacetime. The second brigade was never assigned there. And the existing units only had 50% of the numbers they were meant to have.

This is not surprising at all, since the 59th Brigade was restoring its combat capability after having left the Joint Forces Operation and was undergoing training at several training grounds in different parts of the country [the Joint Forces Operation (JFO) is a term used from 2018 onwards by the media, the Ukrainian government and the OSCE to identify combat actions in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts against Russian military forces and pro-Russian separatists – ed.]. Its core part, based in the south, comprised about 1,300 people.

The 137th Battalion was on duty on the southern isthmuses, observing the Russians. There were 300 marines there, half of them conscripts.

In other words, about 1600 military personnel constituted the core forces in the south on the eve of the Russian offensive.

The additional forces included a tank company, five artillery battalions – some of which had no artillery batteries, an air defence battalion and support units, representing another couple of hundred people in all.

By way of comparison, Major General Sokolov said there were 12 brigades in the JFO area at the time:

"Most likely, there were not enough assets and personnel. The enemy concentrated their troops in an extensive stretch from Belarus to Crimea. There were not enough forces, and we had to keep troops in the Joint Forces Operation area, cover Kyiv, cover the North, Slobozhanshchyna [northeast Ukraine], and the Kharkiv front."

The commanders of the 59th Brigade and the 137th Battalion, hesitating whether to speak about this matter, eventually admitted that they had been assigned to combat zones in the south that were much larger than the military regulations stipulated.

"The enemy's routes had to be blocked in areas under threat – usually motorways. That's why the combat zones cover them," explains the then-commander of the 59th Brigade, Oleksandr Vynohradov.

A battalion of 300 marines held a 238-kilometre zone.

"Although it was supposed to be 3x5 kilometres by all tactical standards," says ex-commander Vadym Rymarenko, "The experience of the JFO and ATO indicates that the battalion occupied a wider stretch than it was supposed to, but not by much. This zone required 14 brigades."

The marines served as the first line of defence. They built three strong points near the Chonhar, Kalanchak and Chaplynka checkpoints. Each of them had 30-40 soldiers on guard. A 120mm mortar was the heaviest weapon they had.

The 59th Brigade was not in theatre; it was based at the Shyrokolanivka training ground near the city of Mykolaiv. The combat zone it was assigned to was to be occupied in the event of an attack, forming the second line of defence after the Marines. This line was 14 times the size of the norm.

"I had a zone of about 140 kilometres, with nobody to my left or right," Vynohradov says.

No positions were set up in this area before the invasion. The reason is the same as mentioned above: it was technically peacetime until February 2022, and therefore the military were forbidden to dig in on private land. The territories deep in Kherson Oblast, beyond the isthmuses, were not mined for the same reason.

Still, Vynohradov and his brothers-in-arms knew their area well. They literally trod it with their feet on the ground - the military term for reconnaissance.

"I've had several reconnaissance missions since November 2021," recalls the former commander of the 59th Brigade. "Each unit commander assesses the terrain to see where to deploy units, where there are important heights, and where artillery should be placed. In civilian terms, it's a survey of the area."

Later, it turned out that the Ukrainian defence line had been well-known not only to Ukrainian troops but also to the Russians. Ukrainian soldiers would later capture some Russian maps and other staff documents during the battles near Mykolaiv.

"They had our positions marked on their maps," says Vadym Rymarenko, then commander of the marines.

He scrolls through the photos of those times on his smartphone. The colonel finds the "commander's operational map" among the shots of the vehicles that had been hit and burnt to ashes.

Judging by the marks, this map was used by the Russian occupying 126th Separate Coastal Defence Guards Brigade. This traitorous unit is the former Crimean 36th Separate Coast Guard Brigade of Ukraine, which switched sides in 2014.

The captured map showed the line of the Russian offensive and the positions of both Ukrainian defence units.

January-February 2022: Final preparations before the war

The final month before the invasion was tense on both sides of the border.

Commander Andrii Sokolov held a meeting on 14 January. Representatives of the 59th Brigade and 137th Battalion, unit commanders, as well as officers of the National Police, the State Border Guard Service and Ihor Sadokhin, Chief of the Security Service of Ukraine's Anti-Terrorist Centre, attend the meeting.

"The units that were supposed to perform the tasks of defending the South were briefed," Sokolov describes the January training. "This involved a practical field exercise, and the tasks, withdrawal routes and defensive lines were clarified."

The 137th Battalion commander is convinced that numerous practice drills and the study of retreat routes helped him save more people on 24 February.

Sokolov also planned to conduct staff training. However, this was postponed several times as the situation deteriorated, so the major general never held them.

At that time, the 59th Brigade, which was supposed to be the second line of defence, was still stationed at the training ground near Mykolaiv. It was moved closer – to the training ground in Oleshky Sands – only 10 days before the invasion.

The sappers performed the last inspection of the mines on 15 February. As usual, they recorded it in a logbook.

Lacking the comprehensive set of forces required even for peacetime, Sokolov realised that he had a significant defence gap:

"There were no forces at all on the Melitopol front. I sent my reserve there to cover it at least to some extent."

A motorised infantry battalion of the 59th Brigade constituted this reserve. Sokolov describes it as the most prepared, with a highly experienced commander. It has been sent to close the "gap" in the final days of peace in Kherson Oblast.

Another tank company was sent to the resorts of Zaliznyi Port and Lazurne [both in Kherson Oblast] to protect the coast from a Russian landing.

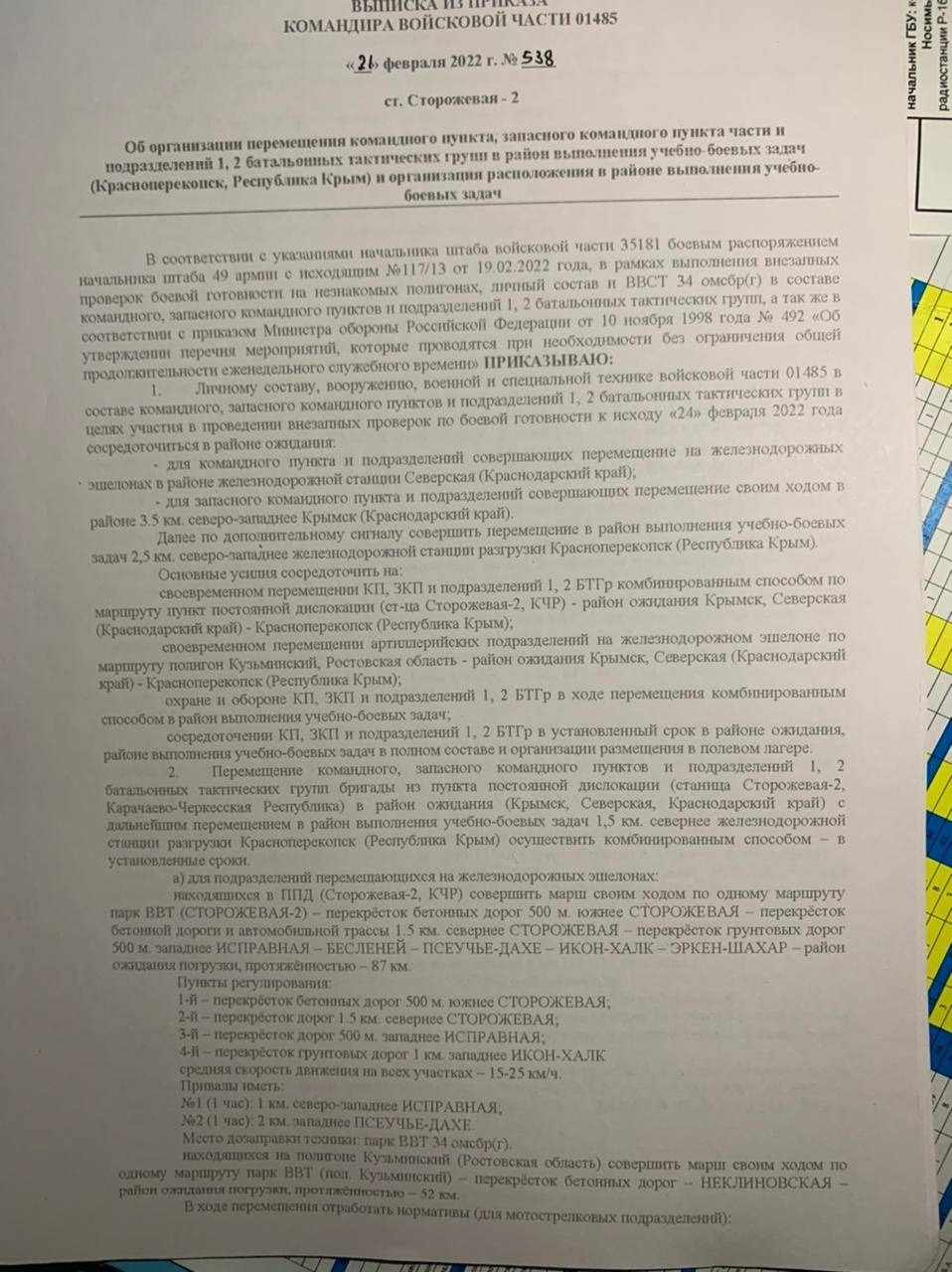

On the same day, 21 February, one of the Russian brigades that would be advancing from Crimea provided its soldiers with a detailed plan. The Russians gave them permission to "perform special (combat) tasks on the territory of foreign states".

The commander of the Russian unit issued an order describing everything from camouflage to movement routes and spots where the Russians might take rest stops on their way to war.

The plans found by the Ukrainians indicated that the Russians were going to pass Mykolaiv and land near Odesa in five days. On the ninth day, they were to block and capture the city of Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in Odesa Oblast. They planned to reach the border with Moldova on the morning of the 11th day and set up their posts there.

"Be prepared to participate in post-conflict settlement activities in the future," the Russian document cynically concludes.

Written on it by hand was the alleged ethnic composition of Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, where, according to Russian calculations, the population consisted of 42% Armenians and only 4% Ukrainians. These data are similar to those that Wikipedia cites from sources dating to the beginning of the 19th century.

23 February 2022

On the very last day before the invasion, without any official explanation, the Russians stopped letting people in and from Crimea. A few days earlier, Ukrainian marines noticed that on the other side of the border, the Russians were clearing the occupied territory before the checkpoint. This was reported to the Ukrainian Command. The order received was to increase vigilance.

On the eve of the invasion, Operational Command Pivden (South) understood that the very next day they may face a Russian invasion.

Lieutenant General Serhii Naiev, Commander of the Joint Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, promptly informed Andrii Sokolov of the situation. Sokolov, in turn, rushed to raise the alert among the units and send them to their positions.

The 59th Brigade was ordered to form a line of defence, about 70-80 kilometres from the training ground. The soldiers could move only at night.

Vinohradov and his unit were ordered to reach the line by 6:00 in the morning of 25 February. Some of his soldiers had set out on the last night before the invasion, but most never managed to do so.

"On the night of 23-24 February, I had already deployed battalion command and observation posts. Communications, up to two motorised infantry companies and mortar batteries from each battalion were already on the defence line. Mechanised companies of battalions, artillery and tank units were ordered to leave already on the night of 24-25 [February - ed.]," recalls the ex-commander of the 59th Brigade.

The 300 marines who were supposed to be the first targets did not sleep a wink that night.

"We all stood in 100 percent readiness," said former battalion commander Rymarenko. "I moved my observation post from stationary to the field in about ten days. Similarly, the observation post company stood in battle formation."

Ivan Sestryvatovskyi, who served in Chonhar had already connected the charges at about 3:00 in the morning in preparation to blow up two road bridges. He was not a sapper, but his task did not require special knowledge. Sestryvatovskyi was trained in advance to activate explosives, and the devices themselves were easy to use.

"There is a machine in which you need to insert two wires, charge the detonator and twist the machine until the light bulb lights up," the sappers explain.

Відео зняте до великої війни. На ньому військовий, який мав підірвати мости на Чонгарі, вчиться запускати підривний механізм.

— Українська правда ✌️ (@ukrpravda_news) September 20, 2023

21 вересня читайте на "Українській правді" великий матеріал, частиною якого буде це відео. pic.twitter.com/26XQZNc6vG

The last hours before the invasion, the military command sat at headquarters, staring at their monitors. Through the flight tracking programme, Sokolov, the duty officer and the air defence chief, watched what was happening in the sky over Crimea. Dozens of Russian military aircraft were circling above.

"We counted them and lost count somewhere at the 30th plane," Sokolov remembers.

On the same day, Ihor Sadokhin, head of the Security Service of Ukraine's anti-terrorist centre, who a month ago had participated in training with the military, reassured attendees of a closed meeting of the civil authorities in the Kherson Oblast State Administration: there will be no invasion.

Later, he became one of those high-ranking Security Service of Ukraine officials who were served a notice of suspicion of treason. In the spring of 2022, information appeared about his detention.

"It is believed that it was he who gave the enemy the grid of minefields and coordinated the actions of Russian aviation when he accompanied the column of the Kherson Security Service of Ukraine in evacuation," says Oleksandr Samoilenko, chairman of the Kherson Regional Council.

How the Russians attacked the south and the Ukrainian Armed Forces fought for Kherson

24 February. 3:50 a.m.

"Commander, look, the Russians struck their own positions."

Commander Rymarenko of the 137th Battalion clearly remembers the moment when he heard this phrase from his subordinate. The Russians covered the territory between the Titan plant in Armiansk and the Ukrainian posts on the outskirts of Chaplynka with artillery fire.

The Armed Forces of Ukraine foresaw such behaviour, suggesting that it could be a false flag operation.

"We received information on the 23 [February - ed.] that the enemy could fire at the Titan plant and then accuse us of doing this, making it a casus belli in order to trigger some actions on our front," Sokolov explains. "At first I thought that was what was happening."

Later, the servicemen realised that this moment was probably decisive for the bridges that could not be blown up.

"After analysing all the actions, I realised that the Russians had cleared our minefields with missile artillery," says the ex-commander of Operational Command Pivden (South).

In a comment to Ukrainska Pravda, the sappers confirms his words: this kind of thing happens quite often.

"During mortar fire or shelling, if debris falls on the power grid, it damages it, and therefore no explosion is triggered, [the explosives - ed.] simply do not explode," explains a serviceman of the 808th Separate Regiment, who was engaged in mining in the south.

The military command drew conclusions from the experience in Chonhar. The head of one of the units involved formulates them as follows:

"Bridges must be destroyed in advance if there is a maximum threat that we will not be able to hold back the enemy."

But he adds that in the case of Chonhar, to make a decision whether or not to blow up bridges ahead of time would have been much more difficult than it might seem, because the context was different.

There was no martial law at that time; the Russians did some sabre-rattling on the border for a long time, and the central government publicly reassured Ukrainians that talk about invasion was simply fear-mongering. No one could be sure until the end that on that particular morning, the rattling would not be simply another distraction or provocation.

5:00 a.m.

The defenders received the "Red-999" signal, which meant full-scale aggression.

Planes circling over the Crimea flew over the Azov and Black seas and launched massive missile attacks on mainland Ukraine.

"The first was the attack on almost all places of deployment of our units, command points, starting positions and air defence system command points, and the airbase in Melitopol. Almost all of the military facilities in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblast [were attacked]," Major General Sokolov recalls the first hours of the full-scale war.

Ivan Sestryvatovskyi remained on the front line, waiting for the order to blow up the bridge. But the radio was silent. Radio communications went off immediately, as soon as the Russians launched their attack. The Ukrainian military communicated via WhatsApp.

"If communication fails, then those responsible were to blow up bridges on their own," according to Rymarenko, the ex-commander of the battalion.

Sestryvatovskyi did exactly that. He tried to blow up bridges.

"But there was no explosion. I tried to blow them up, but there was no explosion. I should have seen it, as I was standing near the bridges, on the first line [of defence – ed.]," the marine told Ukrainska Pravda. "I tried to reconnect the charge, to check the wires again: maybe there had been some error, something had been connected incorrectly. Reconnected, tried again. I did this three times, but there was no explosion."

According to the sappers who had mined the Chonhar bridge, two spans were supposed to collapse. This did not occur.

But this bridge was not the only one to remain intact.

The marines managed to blow up three of the four dams, although one of them did not suffer significant damage. A similar fate awaited the railway bridge in Chonhar – the explosives had blown up, but there was no destruction. A bridge that was in fact damaged had been located further inland, in the vicinity of Chaplynka.

Finally, at the cost of his own life, the sailor Vitalii Skakun blew up the Henichesk bridge, for which he posthumously received the title of Hero of Ukraine.

This bridge, the only one on the isthmus, was supposed to be blown up in another way, there were no pre-connected power grids on it. The reason was that the bridge was located a little further from the Russians, deep inland, and there were not enough people who could guard it around the clock.

But everything was ready for the bridge to be blown up. In the neighbouring village of Novooleksiivka, trailers loaded with explosives stood constantly at the ready. Skakun was supposed to take them to the bridge, connect the wires, move away to a safe distance and activate the device. The sailor managed to do everything except leave the bridge in time.

The soldiers have two explanations for why that happened.

"As I was told, the wire was broken, he ran there and connected it. He did not have time to leave, because the wire was not long enough," says Vadym Rymarenko, then commander of the battalion where Skakun served.

According to Major General Andrii Sokolov, due to Russian shelling, the sailor was blown up along with the explosives with which they had already covered the bridge.

6:00

By land, the Russians were advancing on two main fronts: Kherson and Melitopol. On the Kherson front, they advanced along two different routes to bypass Ukrainian positions and encircle Ukraine’s defence forces.

Ukraine’s 59th Brigade started advancing [towards the Russian forces], but it was unable to reach its defensive line. It engaged the Russians in different locations throughout Kherson Oblast and was suffering losses.

"We were outnumbered 1 to 15, maybe even 1 to 20, in terms of both personnel and equipment," says Oleksandr Vynohradov.

His brigade had to fight around 10,000 Russian personnel, up to 120 tanks, around 100 artillery systems, 40 multiple-launch rocket systems, a dozen military aircraft (Sokolov says there were 140 of them) and up to 40 helicopters.

Vynohradov had only just over 1,000 personnel, around 30 tanks and fewer than 10 howitzers. His battalion and artillery were supposed to cover Melitopol.

7:00

"The battalion held out until 07:05 am," says Vadym Rymarenko, battalion commander and the commander of the first line of defence. "At 07:05 I ordered my soldiers to retreat because the Russians had broken through our defence and started to encircle us."

The marines split up: some retreated towards Kherson, others towards Melitopol.

Rymarenko estimates that the Russian troops outnumbered the soldiers of his 137th Battalion by a factor of 80:

"Only two thirds of our battalion’s personnel survived. We started off with 31 armoured personnel carriers, but only had five by the time we were withdrawing."

Around the same time, the tank company positioned on the shore of the River Dnipro also broke through the Russian encirclement. Dmytro Dozirchyi, the company commander, said at the time he did not even fully realise he was surrounded by Russian forces:

"The commanders didn’t tell us what our final destination was: they led us from one point to the next."

The sappers from the 808th Regiment, who stayed behind to rig bridges located deeper inland, were retreating at their own risk. They drove a civilian bus through a column of Russian forces.

"The Russians must’ve failed to realise we were their enemy. Everything was so confusing. We ended up just quietly leaving in the [Russian] column," says one of the soldiers who, like many of his brothers-in-arms, still remembers every single detail of the day’s events.

12:00

"People saw 20-25 helicopters land on the Antonivka bridge," says Oleksandr Vynohradov, former commander of the 59th brigade.

The bridge was one of the very few crossings over the River Dnipro. The other crossing – the Kakhovka bridge – was located upstream and was already under Russian control.

Vynohradov explains that the Antonivka bridge was the evacuation route not just for the military personnel, but also for civilians:

"Many civilians were fleeing the ruscists on the southern front – from Hola Prystan, Chulakivka, Kalanchak. The enemy air assault units didn’t let anyone through, firing point blank."

This could have been one of the reasons why the bridges over Dnipro were not rigged with explosives and blown up. Doing so would have left Ukrainian troops and civilians without a means of escape.

But Major General Sokolov, who was responsible for the defence of the south, says that the defence of this area was not his responsibility:

"The River Dnipro is strategically significant. It was supposed to be a strategic defence line, and a different military unit was supposed to be in charge of it. Because given the resources we had, it was unrealistic, to put it mildly, to hope that our group of forces would be able to hold back enemy forces in Kherson Oblast and then also prevent them from crossing the Dnipro."

The brigade decided to break through the encirclement on the Antonivka bridge. Over the course of the day, two Ukrainian tank companies – under the command of Dmytro Dozirchyi and Yevhen Palchenko – fought for the bridge. Both Dozirchyi and Palchenko were awarded the title of Heroes of Ukraine for this operation.

14:00

Kherson’s 124th Territorial Defence Brigade was only allowed to join the fight in the afternoon. Before 24 February, it comprised six battalions, 20-40 people each. It did not receive a mobilisation order that morning.

"The order wasn’t issued until around 14:00. Until then, we were calling and vetting people, but we couldn’t officially enlist them," says Dmytro Ishchenko, the brigade’s commander.

The Territorial Defence Forces were poorly organised; this was the main issue, which could be traced back to before the full-scale invasion, and was largely the fault of the authorities. Kherson’s defence forces were given the building of an abandoned school, where they couldn’t even store their weapons.

They were forced to store ammunition and weapons at another site. On 24 February, when every minute counted, they therefore had to waste precious time travelling to their storage facilities.

Read more about the events in Kherson here: The battle for Kherson: the defenders that stood firm to the end

The evening of 24 February

In the evening, the tank crews that had broken through the encirclement on the Antonivka bridge took up defensive positions on the right bank of the Dnipro River.

They continued to fight the Russian forces, which were by then only dozens of metres away, though their tanks were damaged. Eventually they were forced to retreat –taking up and retreating from another five defensive lines until they were entrenched in the city of Mykolaiv. Reserve forces had found their way to the city by then.

Meanwhile, the South Command headquarters were relocating to the Melitopol front. From that night on, it would be based in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

"By the end of the 24th, we were given reinforcements: a National Guard regiment, a public order patrol unit, and the 110th Brigade of the Territorial Defence Forces, the one that was based in Zaporizhzhia," Major General Sokolov recalls.

The personnel under his command were first based in Vasylivka; they made an attempt to establish control over Melitopol. Sokolov says that control over Melitopol was "there for the taking" and there was no organised resistance or defence.

"No one was controlling Melitopol at the time, so enemy troops were able to approach the outskirts of the city. We managed to fire on some [Russian] convoys; our Uragan (Hurricane) multiple-launch rocket systems did a good job, firing on an enemy convoy.

At night we marched from Vasylivka and entered Melitopol. Unfortunately, the forces we had – two incomplete National Guard battalions – were not enough [...] we weren’t able to hold Melitopol."

Sokolov’s units eventually retreated from Vasylivka as well. He explained that personnel shortages forced them to withdraw. The Ukrainian Armed Forces set up their new headquarters in Kamianske on the Melitopol front, slightly to the north of Vasylivka along the Dnipro.

On both fronts, Kherson forces continued to fight for Ukraine after receiving reinforcements.

***

Major General Andrii Sokolov, who was in charge of the defence of the south, does not deny that investigators have a right to look into the events around the defence of Kherson Oblast. He thinks time and the public will be the judges of what happened.

The rest of the military personnel whom Ukrainska Pravda spoke to for this article are also mostly concerned and offended by the unfounded accusations of demining that are levelled at them online.

"For me, it’s the same as when you’re accused of something but you’re mute and can’t explain [what had really happened]," says the head of a unit in charge of laying mines. "When they talk about mine clearance, I want to interrupt them and ask: Where does this version come from? Another question that I have in light of this is: Does anyone bear responsibility for false information?"

Of course there are questions about the defence of the south. While the government assured Ukrainians that there was no danger, in an effort to maintain calm, 1,500 soldiers were bravely preparing for what they knew would be an unequal battle with the enemy.

A number of military personnel whom Ukrainska Pravda spoke to believe that timely mobilisation would have helped them. But that did not fit with the government’s narrative that there would be no full-scale Russian invasion.

However, the rumour that Chonhar has been cleared of mines is not a swipe at Zelenskyy – even if his opponents think that. If the mines had really been cleared, that would have been the responsibility of the military.

This narrative has already formed the basis for criminal proceedings. The proceedings may end up being both a fair investigation and a convenient tool in the hands of the authorities that can easily be turned against the military.

None of this brings the public any closer to answers to what really happened in southern Ukraine during the first days of the full-scale war.

Sonia Lukashova, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska, Artem Yakymyshyn, Theodore Holmes and Olya Loza

Editing: Monica Sandor