Russia has turned grain into a weapon: how Putin is exploiting hunger and deceiving Africa

Russia has been capitalising on African countries, providing them with the bare minimum of aid and triggering an escalating food crisis.

The grain corridor is no longer operating; Russian forces are attacking Ukrainian ports on the Danube, with tens of thousands of tonnes of grain destroyed. That summarises the past two weeks of economic turbulence in Ukraine.

For months the Kremlin has been trying to persuade the world that the deal to protect Ukrainian ports was for the benefit of Western countries, not for the world’s most vulnerable countries, and that Russia was doing everything it could to help its partners in Africa.

A cursory glance at the grain corridor export data refutes the first claim. As for the second, if Russia is helping African countries by offering free grain and increasing exports to the continent, as it claims, why are countries loyal to the Kremlin sounding the alarm over the blockade on Ukrainian grain?

Answering this question requires an analysis of why hunger is such an acute problem on the African continent, what role Ukraine has in solving the issue, and what Moscow’s true objectives are.

The roots and aftermath of the grain crisis in Africa

Over almost a year of operation, around 33 million tonnes of agricultural products have been exported from Ukraine through the grain corridor, 725,000 tonnes of which were sent free of charge to developing countries under the World Food Programme (WFP).

Ukraine shipped 4 million tonnes of agricultural products to Africa, or 12.24% of all exports within the grain corridor. Wheat and sunflower oil, the goods which African countries struggling with food insecurity are most dependent on, were mainly shipped to the African continent.

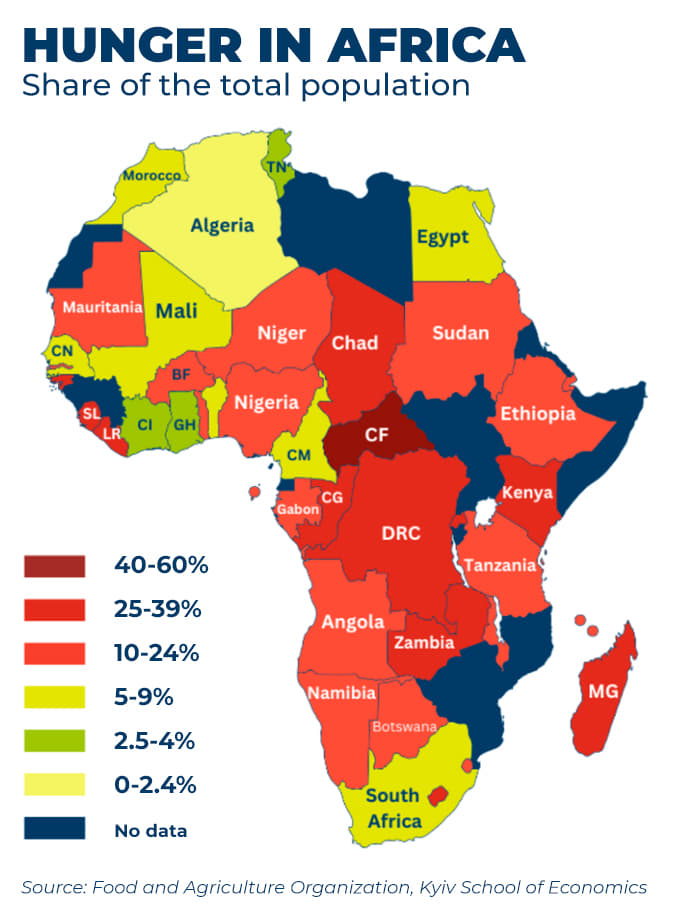

Research conducted by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) Center for Food and Land Use this year indicated that 32 out of 40 African countries for which data is available (54 independent states are located on the African continent) obtain more than 70% of their wheat from imports. This makes them dependent on foreign grain.

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) has called 2023 the year of the most severe food crisis in history. At least 129,000 people may face hunger in Burkina Faso, Mali, Somalia and South Sudan.

There are several reasons for the critical situation in a number of African countries. Firstly, the African continent is import-dependent on some products, making it highly sensitive to global food prices. These are primarily wheat, vegetable oils (sunflower and soybean), rice, and maize (although to a lesser extent).

The population in Africa is growing rapidly and production can’t keep up, so imports increase every year. Egypt, the world's largest wheat importer, provides a good case study.

Just in Egypt, annual wheat consumption has exceeded 20 million tonnes since 2018, with less than 9 million tonnes of that coming from domestic production. A study by the World Trade Institute indicates that Egypt imported the rest.

Imports account for 60% of the wheat and 50% of the vegetable oil consumed in Africa.

Ukrainian and Russian exports make up a significant share of the grain imported. The UN estimates that 15 countries on the African continent received over 50% of their food from these two nations in 2020. This situation leaves these countries dependent on their suppliers, and finding a new supplier is both challenging and costly.

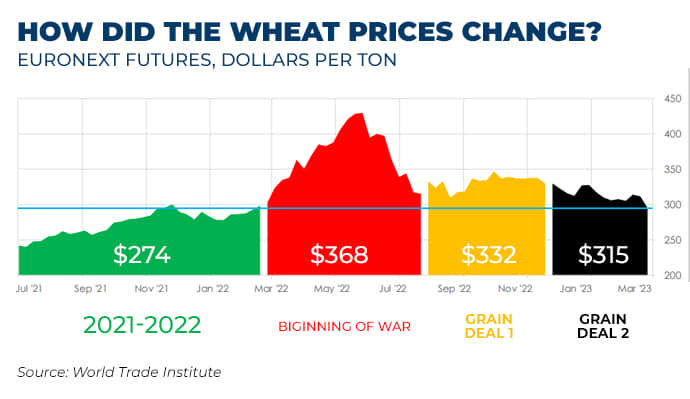

And even if the African countries at risk manage to find alternative suppliers quickly, they will have to overpay for these imports. Seventeen months into the war, grain prices have never recovered, remaining above the 2021 levels.

Africa also depends on fertiliser imports, with prices for these products rising 3-4 times compared to 2020. The reason for this was the energy crisis triggered by the Russians, pushing gas prices up to US$3,500 per 1,000 cubic metres. Gas is critical for the production of ammonia, a key ingredient in nitrogen fertilisers. As a result, domestic agricultural production in the continent has become much more expensive.

The interaction of these two factors led to an average 23.9% increase in food prices in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020-2022. This is the largest increase since the global financial crisis in 2008, states the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Given that food accounts for about 40% of consumer spending on the African continent, this factor alone made the average food shop in the region 8.5% more expensive. Many people found themselves unable to afford food.

The third influencing factor is that global inflation has curtailed the ability of African countries to raise funds. As central banks increase interest rates, investments in developing countries became more expensive. No government has been able to issue a Eurobond since the spring of 2022.

African states lacked the financial means to pay for the already expensive grain, and they were also unable to raise funds on world markets to pay for it.

These three factors are structural, and to solve or at least mitigate them, long-term measures are required, not stopgap solutions.

Temporary relief

The grain corridor performed several important functions for improving the situation in Africa. As well as physically providing Africa with the necessary grain, the general increase in the supply of wheat, corn and sunflower oil meant global purchase prices dropped, including for African countries.

As Economichna Pravda reported, over the past year and a half Russia has targeted key markets for Ukraine. Firstly, this applies to North Africa - Egypt and Morocco. At the same time, Ukraine remains a significant supplier of food for these markets.

African countries are considered conservative and pragmatic in the way they conduct trade. Both state traders and the private market primarily look at prices. Russia takes advantage of this and offers lower prices than their competitors.

Ukrainian traders are forced to compete in order to continue exporting their products, pushing them to lower prices. Together with expensive logistics, these costs fall on the shoulders of farmers, already leading to a reduction in the amount of cultivated land in Ukraine. In the future, this will mean millions of tonnes of grain will not reach consumers.

Pavlo Martyshev, an analyst at the Agrocenter in the Kyiv School of Economics, notes that the world market has become less sensitive to Ukrainian food supplies. However, this is the result of circumstance, not a pattern.

Although grain prices haven’t reacted to the shutdown of the grain corridor as much as the first time, the impact on prices is offset by good harvests in the world's largest grain exporters, including Brazil and the United States. According to the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization, the 2023/2024 market year will be a new grain harvest record.

He expects that closer to winter more serious climate risks may appear, and then prices will rise, making Ukrainian grain more important for the world market.

Pseudo-saviours from hunger

This year, the world food price situation has been saved by the weather. However, the structural problems that caused a potentially critical state of hunger and malnutrition in African countries were not solved by chance.

After withdrawing from the Black Sea Grain Initiative, the Russian Federation once again presented themselves as the "saviour of Africa" and offered Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Mali, the Central African Republic and Eritrea a supply of 25-50 thousand tonnes of grain each over a period of 3-4 months, free of charge. This quantity is small enough to be loaded onto a single vessel, so unsurprisingly, the African countries ignored the Kremlin’s offer.

"We offered to implement the Black Sea Grain Initiative, talked about the need to open the Black Sea, and said that we would like the Black Sea to be open to world markets. We did not come here to ask for any gifts for the African continent." - said the President of the Republic of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, at a meeting with Putin.

This tale could be concluded with the familiar proverb ‘beware of Greeks bearing gifts’. In recent years, the Russian Federation has done nothing to fight hunger in African countries, as the following statistics demonstrate:

Firstly, only 5% of Russian grain exports were destined for Africa last year. According to Martyshev, in 2022 Russia did not participate in humanitarian grain deliveries at all and only partially helped Moscow-friendly Syria.

"In 2022, open databases show that less than 5% of Russian wheat exports went to poor African countries. Russia is not helping its partners at all," Martyshev explains.

At the same time, Ukraine delivered more than 170,000 tonnes of grain to countries such as Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Yemen free of charge during the six months of the Grain from Ukraine initiative.

Secondly, Russia did not introduce any simplifications or favourable terms of trade for the export of its grain to African countries.

Instead, tax duty in the country is set at 70% on the difference between prices per tonne on the world market and a set marker of $200 per tonne of wheat. So the less grain there is on the world market and the higher world prices are, the more funds enter the Russian budget, helping to finance the war against Ukraine.

Thirdly, the Russian Federation barely helps the UN with the World Food Programme (WFP). WFP funds come from governments, corporations and individuals.

According to the UN WFP, the largest contribution was made by the USA last year - $7.2 billion or 0.03% of the country's GDP. In second place is Germany - $1.8 billion, also 0.03% of its GDP. Ukraine's contribution is $15 million, which is 0.04% of GDP.

Last year, Russia contributed $30.6 million, which is 0.0008% of its economy. "Russia is using the idea that they are the ‘saviours of Africa’ for political gain, yet they have one of the smallest contributions to the Food Programme of any country. They haven’t changed the regulations on exports, and so grain remains very expensive for African countries," - summarizes Martyshev.

* * *

Russia's war against Ukraine has put African countries in an even more risky position than before. Moscow has deprived the continent of 30 million tonnes of grain, manipulated food prices and made money from famine, offering one small ship of grain to support their image as a "saviour".

It is unsurprising that African countries are not satisfied with this ‘offer of help’, and have called on Russia to restore the grain corridor. Ukraine’s millions of tonnes of grain provide a stable solution, unlike Moscow’s miserly quick fix.

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn and Yelyzaveta Khodatska

Editing: Bea Barnes