Czech engines, US electronics. How the Russian-made Lancet attack UAVs expose holes in anti-Russian sanctions

Western parts have no problem reaching Russia's defence industry, and this is no longer news. How are Western companies helping the aggressor to boost production of kamikaze drones?

Experts often say the Russians only fight with Soviet-era weapons and capture cities solely through "cannon fodder assaults". However, this is not entirely the case.

Russia has many powerful weapons capable of causing hard times for the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The Lancet attack UAVs is one of them. It's invisible to radars, its electric motor doesn't make loud noises, and its warhead is usually enough to damage even heavy vehicles.

The Russians have used about 850 Lancets in eighteen months of the war. Only a fraction of them made it to their targets, but the Ukrainian military often refers to these drones as one of the primary problems on the battlefield.

"I had my second birthday yesterday. A Russian Lancet missed by three metres, and that saved us. My brother-in-arms – the first to see the drone and shout 'run away' – saved us," said Andrii Starukh, a wounded soldier from the 47th Mechanised Brigade, describing his encounter with the Russian-made UAV.

Back in July, the Ukrainian General Staff said Russia had only 50 Lancets left, and yet the Russians are still using these drones. Kamikaze UAVs are still flying by the dozen as the Russians continue to produce them.

The Lancets are stuffed with sophisticated electronics not produced in Russia. However, Western parts have no problem getting to the aggressor's military factories. The flows are large enough to ensure that Russia can both maintain the existing production rates of these drones and expand them many times over.

Although it seems that the maximum has been squeezed out of technology sanctions, in fact, there are still many obvious gaps.

Western parts, Asian machines

The world began talking about Lancets following a story on a Russian TV channel a month ago. It featured a vivid propaganda image: a kamikaze drone production facility set up on the site of a former shopping centre abandoned by Western brands.

The story claimed that the Russians had boosted the production of Lancet UAVs by 50 times compared to 2022. This figure alone means nothing, as Kremlin propagandists usually tend to overstate production figures. Furthermore, there is no point in comparing it to last year, as the production volumes were low then.

However, the video, showing a room with dozens of Lancets, raises a logical question about technological sanctions against the Russian Federation: how is this even possible?

Zala Aero, a Russian company owned by the Kalashnikov corporation, produces these drones. Neither the manufacturer of Lancets nor its owner, Alexander Zakharov, whose family has an apartment in London, have been subject to Western sanctions.

Russian companies are banned from importing drone parts, yet this ban is not effective. Many Western parts may still be seen in Lancets, and ZALA's facilities feature much equipment from Asian countries known to be friendly to Ukraine.

Russian propagandists featured several machines from Japan and South Korea in the previously mentioned story. These include a Fanuc robotic machine, a Doosan milling and drilling machine, and a Hyundai Wia vertical machining system.

Ekonomichna Pravda (EP) obtained a report on the Russian production of Lancets from the Ukrainian President's Office, jointly compiled by Ukrainian special services and research institutes. It also mentions equipment from the Swiss company Essemtec, Japanese company JSW and Chinese company Jiangsu Huawei Machine. Most of the equipment reached Russia after Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

The components in Lancets are often manufactured in the European Union. It has recently emerged that the engine mounted on the drone is an AXI 5330/18 made by the Czech company Model Motors.

Model Motors produces electric engines for sports aircraft, helicopters and vessels. The company replied to EP that it had not been making these engines for a year and that they "could only have got to Russia through third countries". How true is this?

Roman Steblivskyi, an analyst at the Trap Aggressor project, found that the Russian company Entep reported the purchase of these engines in December 2022. This means that they were purchased almost a year after the start of the Russian aggression against Ukraine rather than being taken from the supplier company’s stocks.

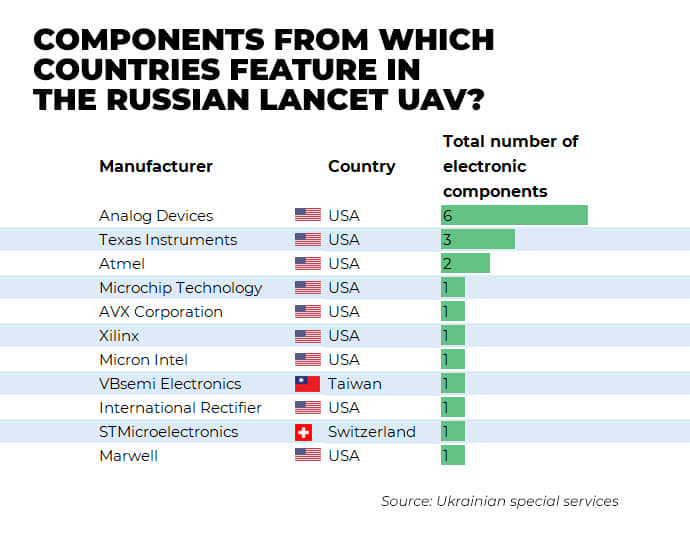

Besides the Western-made engines, the Russian Lancets contained electronics from China, Taiwan, the USA, Switzerland and South Korea.

US-made XILINX microprocessors provide image processing, while Nvidia modules ensure target acquisition. The navigation system is based on the Russian GLONASS system, but microchips from the Swiss company U-blox are required to establish communication with satellites.

One of the critical components in producing any UAV is printed circuit boards, requiring such materials as photoresist and fibreglass, as well as related equipment and expendables. Despite the sanctions, Russia keeps getting all these components from various Western and Asian countries.

After all, these drones are equipped with many purely civilian electronics. These include the cheapest chips used in children's toys or Samsung vape batteries.

How do the parts reach Russia?

Civilian goods seem to be a no-brainer, as you simply cannot control them. However, how do dual-use goods and sanctioned components find their way into Russia?

Czech Model Motors notes that its engines are not on the list of dual-use goods. Their exports are not regulated like the circulation of weapons components. The company's engines have been subject to EU sanctions since December 2022.

Ukrainian special services report that the Russian company Legion Komplekt imported engines for Lancets even after the restrictions were imposed, albeit at a threefold higher price. The supplier was reportedly the German company Hydro-Funk. EP sent an inquiry to this company but received no response.

Russia and its partners often break export controls to obtain avionics and sophisticated microchips. However, once a component is widely available globally, they acquire it through intermediaries semi-legally.

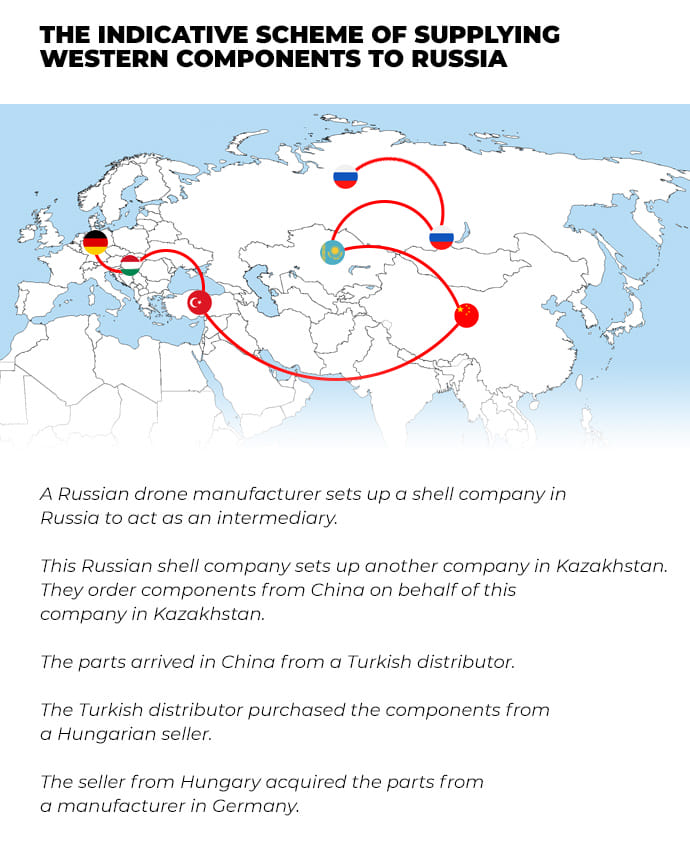

Steblivskyi told EP how this happens: "There are a range of related private suppliers hovering around the Russian military-industrial complex. Nobody knows their names, therefore they are not subject to sanctions. The heads of these supplier companies may establish companies in neighbouring countries, for example, Kazakhstan, and order components from Chinese distributors on behalf of these legal entities.

Chinese companies, in turn, may purchase from Turkish ones. And Turkish companies – from companies in the European Union. There may be dozens of intermediate links in this chain. The goods eventually end up in Russia, and the producers have no idea how they got there."

Ukrainian secret services have painted a typical picture of how chips made by Texas Instruments and Taiwan's Xilinx get into Russia.

There is a Russian company called VMK. They are the largest supplier of these components to Russia. This company acquires electronics from TIL and ATIL – two intermediary companies from Hong Kong and mainland China.

The first one was set up by VMK's CEO Dmitriy Rebus independently with its registered address at a shopping centre. The second one purchases products from the Turkish Turkik Union, which bears all the hallmarks of a shell company and is mentioned in Russian opposition media as a Turkish company supplying Rostec, a Russian state-owned defence conglomerate. This is how the components end up in Russia through several links.

Asian and European machine tools also enter Russia through intermediaries to avoid giving rise to accusations that the manufacturer is collaborating with the aggressor state.

Firms from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are actively importing machine tools. These three countries have previously publicly promised to comply with sanctions and not help Russia circumvent them, but in practice, the situation is quite the opposite.

A report by the Ukrainian secret services found that in December 2022, Kazakh KBD Technologies supplied Swiss equipment from Essemtec to a Russian defence intermediary. Kyrgyzstan's Weitmann Handeln Allianz supplied consumables for this equipment in June 2023. And Uzbek MVizion imported equipment and microcircuits for one of the Lancet manufacturer's contractors.

Selling dual-use goods to Russia is a high-risk business. That's why purchasing components is costlier than doing so directly, especially when you have a dozen distributors on the way to the buyer.

However, Russia has enough money for this purpose. Sanctions have not deprived Russia of the ability to finance the war, so Putin has publicly ordered to increase the production of drones, including Lancets.

How can this be stopped?

The most obvious way is to tighten sanctions against intermediary companies in neutral countries. The example of Turkik Union, which reportedly supplies parts to Russian military industries, proves that such restrictions work.

The Kremlin-aligned news agency TASS reported on 22 August that Turkik Union had been sanctioned by the UK, following which Turkish banks began to refuse to conduct transactions with the company.

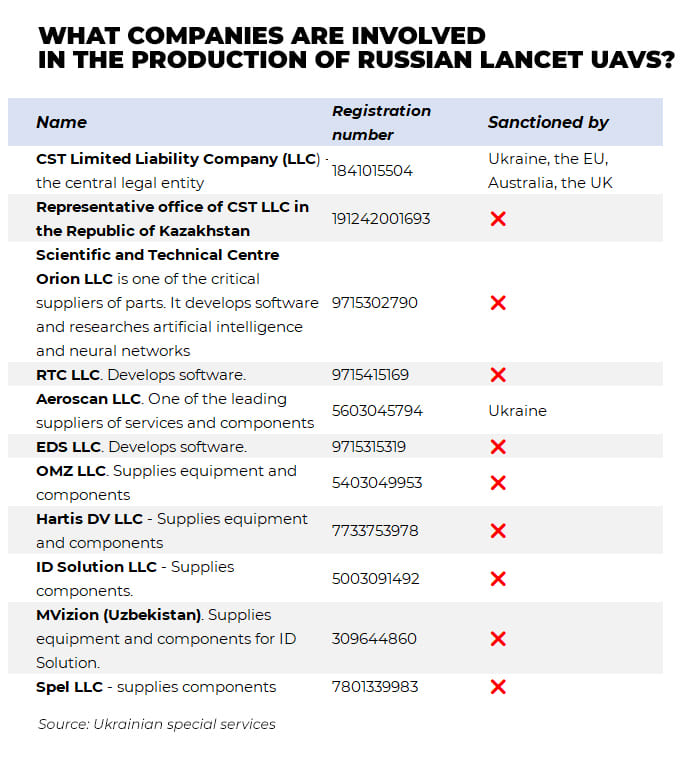

The problem is that Russian and foreign intermediary companies are not often subject to sanctions. A report by Ukrainian researchers and intelligence agencies found that only one of the eleven Russian companies involved in the production and import of equipment and components for Lancets was sanctioned.

Ten intermediary companies importing GLONASS-enabled chips and twelve machine tool importers were omitted from the list. And the list goes on.

"For sanctions to be more effective, they must be implemented by all partner countries. Pushing for restrictions against third-country intermediary firms is quite easy, but not in the European Union. They are reluctant to respond to such requests. The reason is that some EU member states fear that such decisions will push these countries into Putin's arms. But this is a sign of weakness," believes Vladyslav Vlasiuk, an adviser to the Ukrainian President's Office.

"Workarounds for delivering parts to the Russian military-industrial complex remain in place, partly due to the lack of synchronisation of sanctions. The National Agency on Corruption Prevention reports that only 8 Russian companies from the military-industrial complex are on the sanctions lists of all [Ukraine's] partner countries. Establishing a unified international sanctions register would help to address these gaps," says Yaroslav Sydorovych, co-founder of the National Interests Advocacy Network (ANTS).

Another way to hamper the production of Lancets is to expand the list of components banned for sale to Russia. Vlasiuk says parts for drones and missiles are virtually all sanctioned, but there is still a lack of restrictions related to equipment and consumables.

A report by the European Commission's research centre found that various components for producing printed circuit boards, which the Russians use to make technological weapons, have not yet been subject to export controls: epoxy composites, polyamide adhesives, polymer film, testing equipment, etc.

Vlasiuk notes that the problem of circumventing sanctions has long gone beyond the Russian-Ukrainian war. The issue now is that all rogue states and terrorist organisations are able to obtain Western electronics. Therefore, more drastic changes are required in the trade of these parts, up to a complete ban on exporting technological goods to countries that irresponsibly distribute them.

"We could influence manufacturers and distributors in Western countries and force them to obtain information about the final consumer from their customers. Should the components still end up in Russia, we should act against these companies. However, it's sometimes challenging to prove that a product was indeed manufactured by a Western company, as there are counterfeits on the market," Steblivskyi said.

If technically feasible, the production of some of these components may simply be discontinued. As an example, a string of Western firms produce microchips supporting the GLONASS navigation system, used only by the Russians or their allies. Exporting these chips to Russia is officially banned, but Western companies make them anyway, safe in the knowledge that the product will find a buyer in a roundabout way.

Ultimately, to prevent the production of Lancets, we must deprive Russia of funds. You can buy anything in the modern world; the price is the only issue. Therefore, the fact that Russia is manufacturing missiles and drones despite the sanctions is a direct result of the ongoing trade with the aggressor, including the purchase of its gas, diamonds, metals and many other goods.

And to enable Ukraine to counter these massive financial injections, Russian assets in the West must be confiscated. Sadly, this process is also at a standstill.

Bohdan Miroshnychenko for Ekonomichna Pravda

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Susan McDonald

This article was written as part of an ANTS project titled Russian Assets as a Source of Recovery of the Ukrainian Economy, implemented in cooperation with the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and with financial support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).