Finest hour for the defence industry. How can Ukraine produce more weapons?

A day on the battlefield like every other. A unit of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) was getting ready to move into their positions, but to do so, the soldiers had first to cross several kilometres of perilous road which is constantly under fire.

The military used a Ukrainian-made Kozak armoured combat vehicle in the manoeuvre. The Kozak-2 came under fire from a 120mm mortar along the way, but its hull withstood the shrapnel, and no one inside was injured. The driver hit the gas, and the troops reached their destination safely. But what if there were no Kozak?

The AFU does not always receive Western equipment in the necessary quantities, so in this protracted war, Ukraine has to rely on its own production.

Ukraine's domestic production facilities withstood the first months of intense missile attacks, managed to cover their production needs and arrange for the supply of parts, and some of them substantially expanded their workforce.

However, the industry experts interviewed by EP(Ekonomichna Pravda) believe that the potential of the Ukrainian military-industrial complex has not been fully harnessed. The AFU should be receiving many more domestically produced projectiles, missiles, drones and armoured vehicles and be less dependent on supplies from abroad.

Substantial orders from the state are essential if the military industry is to work at full capacity and drive the economy. And although the Ukrainian defence budget for 2022 increased ninefold, only a few Ukrainian manufacturers have received the necessary long-term contracts.

The state often gives contracts to foreign manufacturers, leaving the domestic defence industry unable to produce similar products, and the terms of contracts with Ukrainian manufacturers are not always acceptable.

Military equipment procurement is still operating on an urgent basis. It has become clear that the war will be lengthy, so a strategy to provide the AFU with weapons is essential. There is no way for Ukraine to become a "new Israel" without a long-term plan and investment in the military industry.

The Kremlin has been preparing the ground for new waves of conscription, meaning that Ukraine will need plenty of weapons. And the country needs to get them as soon as possible.

Ukraine’s defence industry is coming back to life

From the very first days of the Russian invasion, no one knew whether Ukrainian military facilities would survive and whether the country would even continue to exist on the global map. The Ukrainian state carried out all defence procurement in haste, buying everything that could be used in combat.

Ukrainian private companies sold equipment to the state that was originally intended for export and emptied out their warehouses; and even if they produced new weapons, they did so under old contracts or using their own funds. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence (MoD) purchased most of the equipment it needed from warehouses in neighbouring countries. Long-term contracts for Ukrainian manufacturers were out of the question.

This was the right thing to do, since when the country's existence is at stake, money should be spent on the most effective means of crushing the enemy. The issue of whether to use Ukrainian or foreign weapons is secondary.

The situation has now changed. The war is dragging on, stockpiles abroad are being depleted, and there is a growing risk that Western politicians may cut back on support if they are not satisfied with the results on the battlefield.

Achieving victory requires relying more extensively on domestic weapons, some of which have never been produced before. For example, Ukraine needs to start mass production of ammunition for Soviet-made artillery, currently in short supply worldwide.

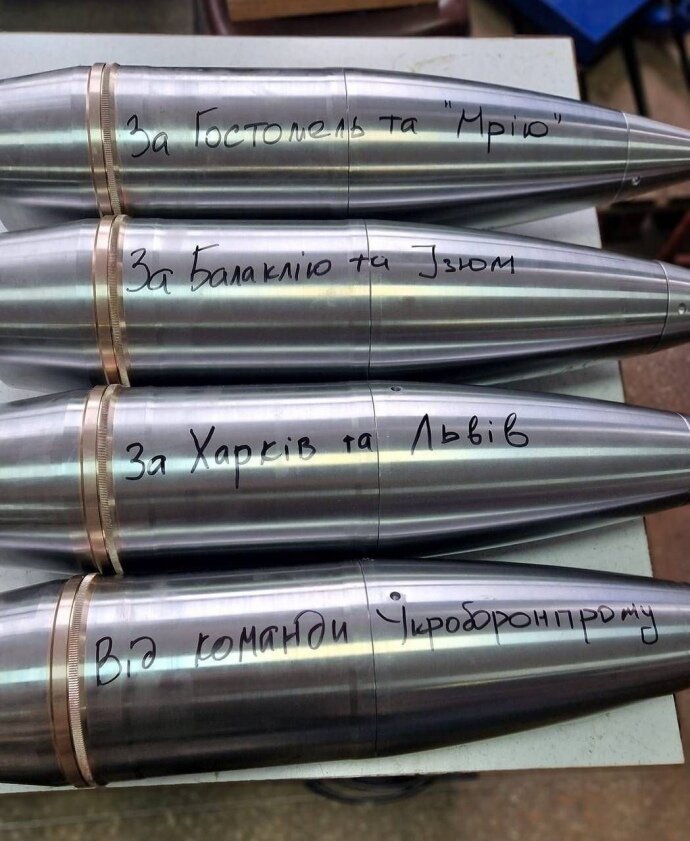

The first mass-produced Ukrainian projectiles were manufactured last year at the facilities of Ukroboronprom ["Ukrainian Defence Industry", the state-owned weapons producer - ed.]. They were costlier than their foreign counterparts, so the MoD had to purchase imported ones. Ukrainian plants could not reduce projectile prices since they did not receive orders from the MoD and did not have the working capital to acquire better equipment.

Only in 2023 was a solution reached between contractors and customers. The market players agreed that the Ukrainian Defence Ministry would order Ukrainian-made munitions first and foreign ones only thereafter.

EP's sources say that whereas in the past, domestic ammunition plants received mostly unpromising month-long contracts, now they are loaded with orders until the end of the year. The production of munitions has been stepped up many times over and amounts to tens of thousands of pieces per month.

There has been a similar development in the drone industry. In the spring, a series of measures were taken to deregulate the UAV industry. Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal said the government would in 2023 place an order for drones worth UAH 40 billion [roughly US$1.09 billion]. The drone manufacturers interviewed by EP confirm that there are indeed significantly more incentives for UAV development compared to last year.

Challenges persist

Ukrainian companies are capable of producing not only projectiles and drones but also rockets, armoured vehicles, artillery, electronic warfare systems, communication equipment, guns, ammunition, etc. However, the problem is that the Ukrainian government's investment in the defence industry is rather slow.

One of the civil servants involved in the defence industry told EP that most of the positive changes are, in fact, due to pressure from contractors. Companies running idle facilities during the war have to appeal to lawmakers, ministries or other government agencies to obtain orders for domestic production.

He said the Ukrainian MoD still acquires many more foreign weapons than Ukrainian ones. On the one hand, this makes sense, as that way the military receives high-quality and well-tested equipment. On the other hand, there should be a balance between foreign and local contractors, so as to enable the production of similar weapons in Ukraine.

Localising production not only increases Ukraine's independence in terms of armaments, but it also stimulates the economy. Domestic companies and their contractors pay taxes, so part of the state's money goes back into the treasury, which funds defence. That makes it possible to buy more weapons, improve them and keep fighting.

"The main problem for us at the moment is the lack of long-term contracts with the Ministry of Defence that include a clear funding mechanism. This is what affects the potential for sustainable development. We cannot produce large volumes in one month and then stand idle for two months," one of the armoured vehicle manufacturers told EP.

Which Ukrainian weapons will conquer the world’s weapons markets after the war

When companies secure long-term contracts, they can optimise production, place bulk orders for spare parts, and confidently plan expansion.

"If we placed orders in advance, Western manufacturers would tell us exactly when the parts would be delivered, and we could better optimise our work. Now we have to beg for free space in their production schedules, with unstable delivery times," says another contractor.

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Ukrainian plants had an additional source of income from export contracts. Foreign customers paid more for Ukrainian weapons than the Ukrainian government, keeping the manufacturers afloat. However, since last year they have not been selling weapons abroad, so now their business is entirely dependent on contracts with the state.

The terms of these contracts have not improved. The current one-year contracts are imperfect: they extend the production cycle and therefore reduce the amount of equipment produced. This is how one of the drone manufacturers explained the problem to EP:

"Each January, the Ministry of Defence allocates the budget. Let's say the AFU needs to purchase drones and places an order for 100 units, which we have to fulfil by the end of the year. The negotiation process begins, as does the allocation of funds, the purchase of spare parts, etc. Effectively, the plant starts production in the spring.

The company may not be able to fulfil the order due to the time lost at the beginning of the year, so in December, the Ministry of Defence refunds part of the money set aside for this contract to the state treasury.

Then everything starts all over again – waiting for the budget to be allocated, negotiating and receiving the prepayment. During this period of time, the plant, in fact, stops working on the order. If we had a contract for three years at once, we wouldn't have this problem. We could just work smoothly and not run into all this bureaucracy," laments the drone manufacturer.

To overcome these bureaucratic difficulties, companies need transitional contracts that would not be affected by the annual redistribution of the state budget.

The manufacturer in question approached the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence with such a request but got a refusal, since the law apparently does not provide for such contracts. After a while, this company was told that it was legally possible to receive 24-month contracts. However, such agreements are rarely concluded in reality.

The Ukrainian MoD isn't the only one purchasing UAVs for the military. Under an experimental government decree, Ukraine’s State Special Communications Service has also been engaged in doing so since the spring. But the contractor says this service is also unable to enter into long-term contracts...

Before the Russian invasion, Ukraine had a tool for long-term ordering. These were three-year procurement plans, making it possible to book manufacturers for several years in advance. However, three-year plans have been cancelled since 2022, and all orders are placed individually, without a clearly defined strategy.

This made sense at the beginning of the war, as the needs of the AFU were rapidly changing and military facilities were suffering from Russian missile attacks. However, there is a demand for long-term solutions at this point. Perhaps the Ukrainian Defence Ministry and other state buyers should consider reintroducing multi-year procurement in one form or another and eventually move from situational to strategic planning for procuring domestic weapons.

Shifting to long-term cooperation will take some work. The EP's sources have said that even now, manufacturers and customers sometimes cannot agree on the prepayment amount. The Ukrainian MoD seeks to be economical with public money, while the contractor wishes to receive larger advances. More flexibility in terms of financing will come in handy when signing multi-year contracts.

For their part, Ukrainian defence companies must do everything to prove themselves a reliable partner to the state. This means meeting delivery schedules, improving their products, coming up with solutions for years to come, and being constructive in negotiations.

In this regard, the dispute between the Ukrainian MoD and Oleh Boldyriev, a former Ukroboronprom project manager, over the production of drones is a good example. Boldyriev said it has been a long time since manufacturers have mass-produced drones, given the lack of government orders. The MoD responded that Ukroboronprom’s companies simply did not provide them with any proposals. Such misunderstandings between customers and manufacturers will definitely not help increase the fleet of Ukrainian drones.

The Ministry of Defence now presents itself as a defender of the Ukrainian defence industry. Ukraine’s Defence Minister, Oleksii Reznikov, calls himself a "Ukraine-protectionist" when it comes to weapons procurement. However, this "protectionism" has not yet been enshrined in specific regulations or established procurement practices.

There have been attempts to use legislation to oblige the state to purchase Ukrainian weapons as a matter of priority, but so far, these efforts have been fruitless. Relevant initiatives by contractors have not even reached parliament. Discussions have been going on for many months.

Ukraine's defence industry has the potential to produce more weapons in the future and to become a powerful exporter after the war. However, the government needs to take a truly strategic approach to the sector, giving it preference, making investments and devoting attention to pressing issues. Sustainable government procurement is a crucial matter.

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Monica Sandor