Putin's path to The Hague through "filtration" and "rehabilitation": how Russia is abducting Ukrainian сhildren

"If the whole world could hear me, I would say that this war must be won as soon as possible so that all children can see their families," says 12-year-old Sashko from Mariupol, who was separated from his mother by the Russians during the "filtration" in Donetsk Oblast.

Sashko is one of the thousands of children taken by the occupiers from captured regions of Ukraine to the Russian Federation under the guise of evacuation and rehabilitation to teach them to "love Russia".

On 17 March, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin and the Russian Commissioner for Children's Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova. They are suspected of facilitating the forced deportation of children from temporarily occupied Ukrainian territories in violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

According to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, at least 19,000 minors have been deported to Russia and Russian-annexed Crimea since the beginning of the full-scale war. It has been possible to bring 364 of them home.

Were all the children deported by force? Who, apart from the Russians, is contributing to the attempts to "Russify" Ukrainian children? What methods does the Russian Federation use to "re-educate" young Ukrainians, and is Ukraine doing enough to get them back?

We talked to dozens of children who have been brought back to Ukraine and established their places of detention, the methods used to abduct them, and the names and positions of the Russians who facilitated the crime.

The details are in this article.

Separation during "filtration"

"They didn't let me say goodbye to my mother," says 12-year-old Sashko from Mariupol.

We meet in Chernihiv Oblast, where he now lives with his grandmother, Liudmyla. Football and games on his mobile phone help him to forget about life under constant shelling.

Last spring, Sashko and his mother were cooking food over a campfire in the partially occupied city. When the shelling began, they did not have time to run to the shelter, and Sashko's eye was injured by shrapnel. In search of medical help, his mother took him to the Illich plant, where Ukrainian military medics treated the wound. However, later the occupiers captured them.

"Russian soldiers in uniform, with machine guns, loaded us into their KAMAZ trucks with the letter "Z" on and took us to some hangars. There were a lot of them; they were wearing masks. They searched us and took away our phones," recalls Sashko.

He adds that they were probably taken to the military base in Sartan. When they informed the Russians that they were civilians, they were sent to a tent city in Bezimenne.

There, Sashko and his mother were met by representatives of Russia’s Ministry of Emergency Situations and registered. After that, some Russian soldiers took the boy's mother away for further questioning. He has not seen her since.

"They said my mother didn’t need me, that I would be sent to a children’s home and then to a foster family."

Representatives of the "Children's Service" of the "Donetsk People’s Republic" ("DPR") came to collect the boy and took him to Donetsk. He was kept in the "republic’s trauma centre" for two months until he found an opportunity to call his grandmother.

"On 19 April, I got a call from an unfamiliar number: ‘This is Sasha. Granny, take me away’," his grandmother Liudmyla recalls. "People tried to dissuade me from going there, they said the Russians might capture me too. But I said, ‘How can I not go if my sweet grandson is there?’"

With the help of the central and local Ukrainian authorities, within a week, Liudmyla was issued with a passport and documents certifying that Sashko was her grandson, and she set off from Kyiv to bring him back from occupied Donetsk.

The journey there and back took nine days.

Doctors say that Sashko no longer has any sight in one eye. The injury will always remind him of the hell he experienced in Mariupol.

The fate of Sashko's mother, Snizhana Kozlova, is still unknown. But he hopes that she will return.

The people overseeing the abductions

The leading overseer of the deportation of Ukrainian children to Ukraine’s occupied territories and the Russian Federation is Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s commissioner for children's rights. She has bragged about becoming the guardian of Filip, a teenager from Mariupol. Filip's mother had died and he lived with his guardians, who are probably still in Mariupol. The fate of his aunt and grandmother is unknown.

The International Criminal Court has issued a warrant for her arrest and she has been sanctioned by several countries.

For several years, Lvova-Belova was a member of the Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation and a Russian senator, and she headed up several charity projects, particularly for children with disabilities. There were reports in the Russian media about the deaths of several of her students and about loans that were allegedly taken out for them.

Lvova-Belova's husband is a Russian Orthodox priest. Together they are parents and guardians to 22 children. Maria calls the removal of children to Russia their "salvation" and rejects the accusations made by the IСС. "We support family reunification in every possible way," she says.

However, as Ukrainska Pravda’s investigation has shown, the "re-education" of Ukrainian children also involves the "children's services" of the Russian-occupied territories, "children's commissioners", and "ministries of education, young people and sports".

We have identified most of the people involved in this process.

The "education" outfit in Crimea is headed by a Ukrainian, Valentyna Lavryk; in the unrecognised so-called "Donetsk People’s Republic" (DPR) by Olga Kaludarova; in the so-called "Luhansk People’s Republic" (LPR) by Ivan Kusov; in the occupied part of Kherson Oblast by Mikhail Rodikov; and in the occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast by Yelena Shapurova. Svetlana Maiboroda heads the so-called "DPR" children's authority, and Anastasia Omelchenko heads the one in Crimea.

The "ministries for young people and sports" in each of the occupied territories are headed by Aleksandr Gromakov, Dmitry Sidorov, Elvira Vitrenko, and Anton Titsky, respectively. Irina Klyueva is the children's commissioner for occupied Crimea, Daria Morozova for the "DPR" and Inna Shvenk for the "LPR".

The "ministries for social policy and work" are also indirectly involved in the abduction of children, as they were the agencies paying child benefits to parents in the territories which were occupied last year.

Denis Strelchenko heads the ministry for social policy and work in the "DPR", Svetlana Malakhova in the "LPR", Yevgeny Markelov in the occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Alla Barkhatnova in the occupied part of Kherson Oblast, Elena Romanovskaya in Crimea, and Anton Kotyakov in Russia.

Irina Pleshcheva, former representative of the Federal Agency for Young People’s Affairs (Rosmolodyozh), oversees "children’s education" in Putin's administration.

Child abduction would not be possible without the assistance of the leaders of the Russian-installed occupation administrations of the Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia. They are: Sergey Aksyonov, Leonid Pasechnik, Denis Pushilin, Vladimir Saldo, and Yevgeny Balitsky.

There are also so-called philanthropists who take an interest in the issue of children in the occupied territories. Russian Orthodox oligarch Konstantin Malofeev is one of them. He and his St Basil the Great Foundation co-founded a project called Happy Childhood. In 2014, he financed terrorist units in Donbas like those of former Russian intelligence officer Igor Girkin.

The foundation established by Aimana Kadyrova, the mother of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, also regularly reports on helping Ukrainian children.

Kadyrov and Lvova-Belova helped to set up a camp near Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, for the "re-education of children from the new territories of the Russian Federation". Those who actively oppose attempts at Russification are sent there.

How does abduction happen?

Ukrainska Pravda spoke to several dozen abducted children, their parents, and volunteers who are helping with the search.

There are several ways in which the Russians abduct Ukrainian children:

- abducting children who have lost their parents;

- separating children from their parents during "filtration";

- taking children away from their families, for example, on the grounds of poor living conditions or danger;

- abducting children from residential children’s homes.

The Russians disguise the act of abduction with a propaganda narrative about rehabilitation and evacuation from dangerous areas or, less frequently, the need for medical care.

In order to legalise the process within the country, Russia has even adopted separate legislation on Ukrainian children.

Last year, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed two laws: one simplifying the acquisition of Russian citizenship by children and their legal representatives, and one simplifying the procedure for Russians to adopt Ukrainian children.

The adoption process is confidential in Russia, which means that it is effectively impossible for adopted children to be found.

"None of Putin's decrees contains any clause or provision that requires obtaining the child's consent or finding out his or her opinion," says Aksana Filipishyna, a representative of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, who has been working on the issue of abducted children since 2014.

"That is, there are no indications that Putin’s state is attempting to comply with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. In fact, these are forced and unilateral actions aimed at transferring children from one ethnic group to another. And that is a sign of genocide," the human rights activist says.

Deportation stories: taken to the "LPR" in Ural military trucks

Natalia, the mother of 15-year-old Artem from Kharkiv Oblast, tells us how the abduction process happens.

Russian occupiers took 13 children from a local children’s home with them as they fled from captured Kupiansk last autumn when it was retaken by the Ukrainian army. Artem, who had come to collect his papers the day before the abduction, was one of them.

"It was just a human shield made of children. The Russians were hiding behind the children, realising that our guys would not shoot at children," Natalia says.

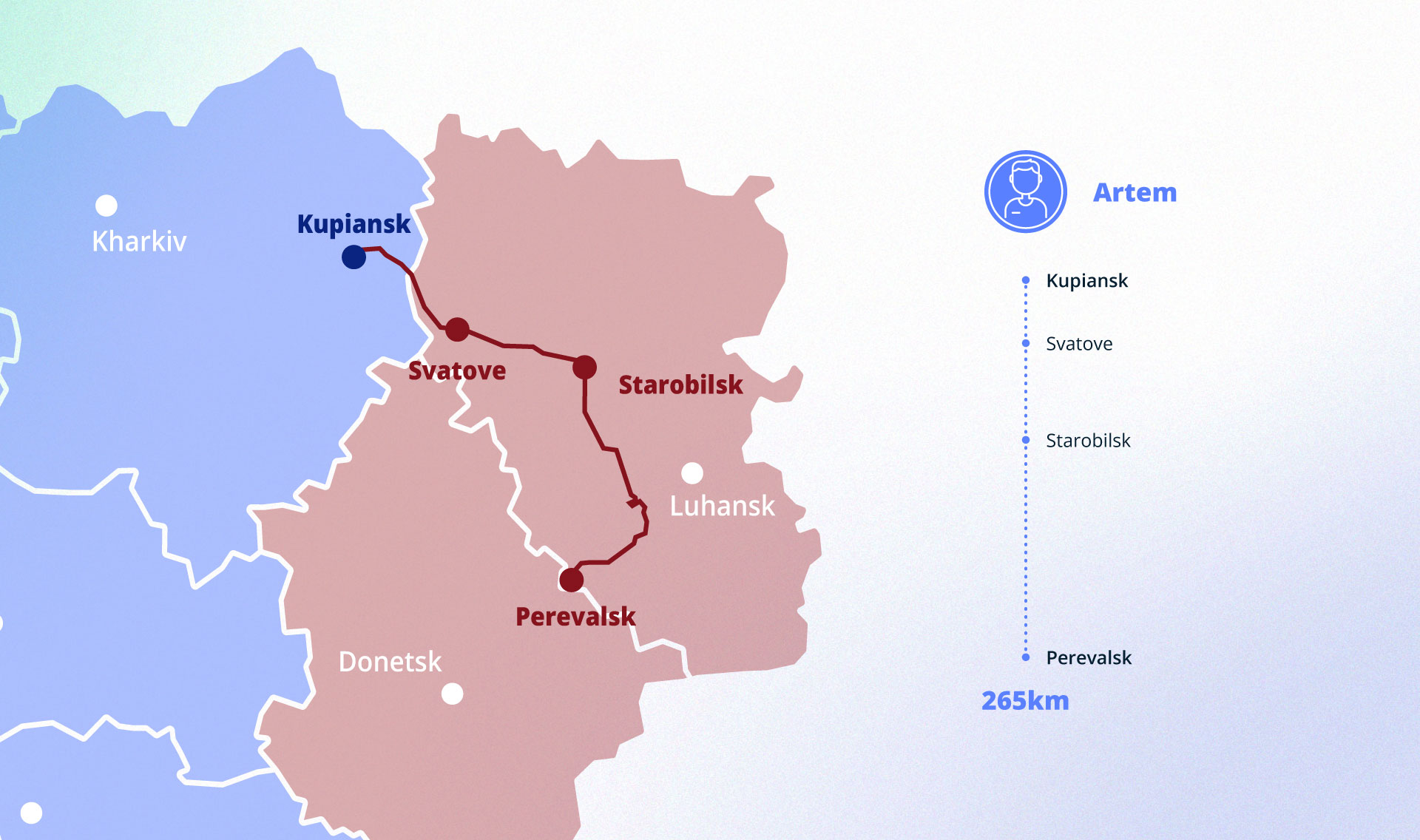

Artem says the Russian soldiers took them out of the city in Ural trucks. They were travelling with a convoy that was withdrawing from Kharkiv Oblast. The children were told that "they were being rescued because Ukraine was advancing".

"There were 13 of us," Artem says, "and it was the military who took us away. First to Svatove, then to Starobilsk. We spent the night there and then we were taken to the Perevalsk children’s home. There were children from Luhansk there as well."

He is reluctant to talk about the care workers there, saying only briefly: "They forbade everything and forced us to sing the Russian national anthem. But I didn’t sing [it]."

The teenager was also forced to work, digging the ground and unloading humanitarian aid. The children were told they might be transferred to Rostov-on-Don, Russia.

Artem kept in touch with his mother the whole time and he knew that he would be taken away soon. After six months of separation, he was reunited with his family: Ukrainian volunteers helped his mother to travel to her son.

The Ukrainian soldiers who liberated Kharkiv Oblast from the Russians have the names of the three brigades of the Russian Armed Forces that were based in Kupiansk on the eve of the withdrawal:

- The 27th Separate Guards Sevastopol Red Banner Motor Rifle Brigade (Military Unit Number 61899), led by Sergei Safonov at the time,

- The 55th Mountain Motor Rifle Brigade (Military Unit Number 55115), commander Denis Barilo

- The 200th Separate Motor Rifle Pechenga Order of Kutuzov Brigade (Military Unit Number 08275), commander Denis Kurilo. According to Ukrainian defenders, Kurilo was killed in action during the battles for Kharkiv Oblast.

Oleksii Lytvynov, a representative of the Kharkiv Oblast Education Department, says that an investigation is currently underway into the care workers at the children’s home who allegedly assisted the Russian occupiers to abduct the children.

Some of the younger Kharkivites were taken by the Russians, with parental consent, to a Russian children’s camp called Medvezhonok (Bear Cub) in Gelendzhik, southern Russia, and to Artek, a children’s camp in Crimea. Vitalii Ganchev, head of the Russian-installed occupation "administration of Kharkiv Oblast", issued an "order" to this effect.

"After the liberation of the region, our military found documents that confirm this," Lytvynov said.

The Russians also abduct children who have lost their parents. Artemii Konovalov, a police officer from Kharkiv Oblast who is involved in the search operations for children, said that 13 children from Kupiansk were killed and several were wounded during an evacuation attempt.

"Two children were then picked up by a local resident and taken to his home," the policeman says. "We then went out and handed the children over to their relatives there. The Russians sent another child to some ‘LPR’ hospital – her grandmother was with her, but the occupiers insisted the parents had to be there."

According to Konovalov, if a child has no relatives other than their father, then the case is referred to the Ukrainian Ministry for Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories, where they decide whether the father can leave the territory, or draw up a power of attorney for someone else.

Daria Kasianova, director of the NGO SOS Children's Villages in Ukraine, who is also involved in bringing children back, insists that the occupiers have blocked all attempts by the Ukrainian authorities to organise a "green corridor" for children with special needs. "I know that there have been constant talks about ‘green corridors’ to let these children out, but they [the Russians – ed.] never agreed," says Kasianova.

Where are Ukrainian children being taken?

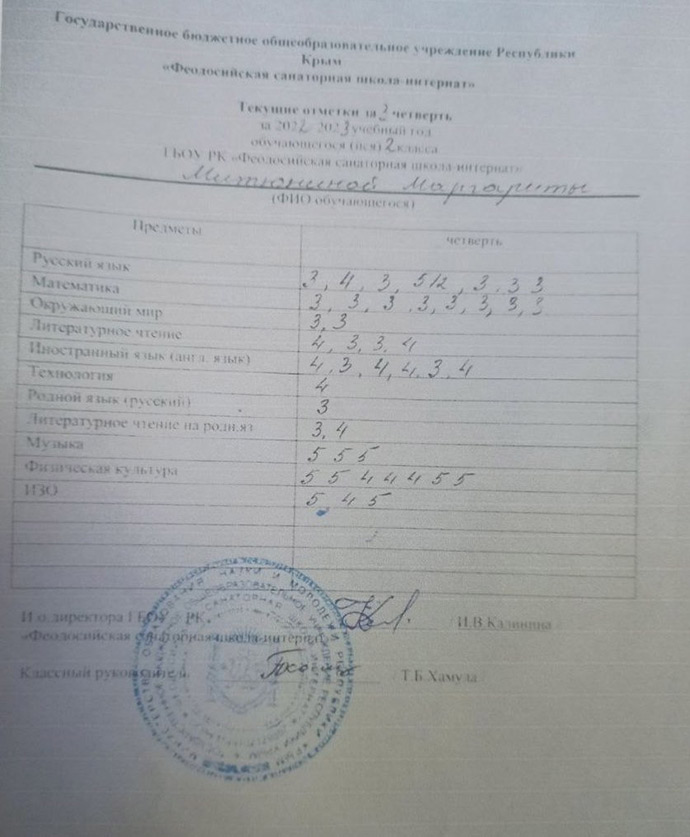

This photograph is of the school report card that eight-year-old Marharyta from Kherson Oblast received at the Feodosiia sanatorium and residential school. She was sent there last year, without her parents' consent, from the then occupied village of Chervonyi Maiak, Kherson Oblast, by two pro-Russian local women who had helped organise the sham referendum.

[State-funded Educational Institution of the Republic of Crimea/Feodosiia sanatorium and residential school/Current grades for 3rd quarter for the academic year 2022-2023 for a 2nd-grade student/Student’s full name/Subjects: Russian language, Mathematics, The World around us, Literary reading, Foreign language (English), Arts and crafts, Native language (Russian), Literary reading in native language, Music, PE, Fine art/Acting headteacher (I.V. Kalinina)/Class teacher (T.B. Khamuda)]

The document transferring Marharyta to her mother from the "children's services" in occupied Feodosiia"It was terrifying, because my mum wasn’t there," Marharyta says.

With the help of volunteers and local authorities, Marharyta’s mother found her child and took her away from the occupied peninsula. Ukrainian law enforcement officers have initiated criminal proceedings on the abduction of a child. Marharyta is now at a Ukrainian school and adds, "This is much better!"

What other places are the occupiers taking our children to?

In addition to the previously mentioned residential school in Feodosiia, Ukrainian children from the occupied districts of Kharkiv, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts have been taken to Yevpatoriia in Crimea, in particular to camps named Shchastye (Happiness), Druzhba (Friendship), Luchisty (Radiant) and Zarnitsa (Summer Lightning).

Most of them are part of Solnechnaya Tavrika (Sunny Taurica, or ST), a children’s home in Feodosiia run by Lyudmila Yermakova, who is close to Sergey Aksyonov, the so-called Head of Crimea.

The children said that ST’s leadership made several visits to the camps. Veniamin Kondratiev, Governor of Russia’s Krasnodar Krai, also came on an inspection. The Russians also took children to the Artek camp in Crimea in the summer.

They also take children to Russia.

Most of these children are taken to Anapa (Vita camp), Gelendzhik (Medvezhonok (Bear Cub) camp), Yeysk (Yeysk sanatorium), or Voronezh (Nemetskaya Sloboda recreation centre).

Orphans are usually taken to residential children’s homes or medical institutions.

More than 50 children who lived at the Oleshkivska children’s home were taken away by the Russians in three groups in the autumn of 2022. The institution’s director at the time refused to cooperate with the Russians, whereupon the occupiers appointed a new one, Vitalii Suk, and he issued an "order" for the children to be taken away.

"The first two groups were taken to Crimea, near Simferopol, to psychiatric hospital No. 5. The third group was placed in Skadovsk [at the Nadiia rehabilitation centre – ed.]. Then something happened to them there, and most of the children were transferred to Russia, particularly to the Kropotkin and the Labinsky children’s homes [in Krasnodar Krai, southern Russia – ed.]. After these ‘tours’, the children returned to the Bilohirskyi psychoneurological children’s home in Crimea," says Myroslava Kharchenko, a lawyer with the organisation Save Ukraine who works with her team to bring Ukrainian children back to Ukraine.

During the occupation of Kherson, the Russians took 15 children from a local children’s home to Russia.

Volodymyr Sahaidak, director of the home, recalls how an anonymous representative of the "ministry of youth and sports" called him and gave him a few hours to gather the children together.

"They said that if we didn't let the children leave now, they’d send soldiers and take them away by force," Sahaidak said.

He managed to hide some of the children; care workers took them to their homes and placed them with friends. But the occupiers did find 15 children and took them away to Anapa, Krasnodar Krai.

"They were looking for the other children. They took all the documentation from me. But I said that the children had been rehabilitated and gone home," says Sahaidak, showing us footage from surveillance cameras that shows representatives of the FSB and the military. They visited the institution almost every day, asking the same question: "Where did you hide the children?"

Vitalii, a care worker from the Kherson children’s home, witnessed the occupiers making a propaganda video about "saving Ukrainian children".

"At first, they were working with a journalist from Krim 24 TV who alleged on camera that we were filling their heads with propaganda against everything Russian, that we were working according to American methods, and they also tried to tell some lie about LGBT people," Vitalii says.

"Then the ‘military correspondent’ arrived. They brought some Buryats with them and wrote a piece for him on a sheet of A4 about how he was saving children. It was so funny. They had FSB officers with them too," the care worker recalls.

All 15 of the abducted children have been taken from Russia to Georgia, and soon they will return to Ukraine.

It is not known where the occupiers are taking children from Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, but it’s likely that they send them to local medical institutions and children’s homes in the Donetsk and Luhansk "People’s Republics".

"Re-education" methods

The rhetoric that "your parents don't need you" and "you have no future in Ukraine" is one of the methods of propaganda that the Russians use on Ukrainian children living under occupation or who have ended up in the Russian Federation.

"They say that Ukraine has abandoned you, they teach you to hate your parents, then [to hate] our state, and then to love Russia," says lawyer Myroslava Kharchenko.

Kateryna, 13, from Kherson, had never been to a children's camp. So when her school offered pupils a free trip to Yevpatoriia for two weeks last autumn, during the occupation of the city, she persuaded her mother to write a letter giving her consent.

But the children were not brought back at the specified time as previous groups had been. Since the Armed Forces of Ukraine were approaching Kherson, the city began to evacuate to the left bank [of the River Dnipro].

"First they claimed there were no buses because they were being used for the evacuation. Then they said it was dangerous for children in Kherson," says Kateryna's mother Viktoriia.

The occupiers suggested that Viktoriia leave for the left bank and said Russian emergency workers would bring her child later. But Viktoriia refused and sought ways to get her child back with the help of the Ukrainian authorities.

Her daughter Kateryna remembers how the Russians in the camp tried to force them to love Russia.

"Every morning we would hear the Russian national anthem, and we had to stand for it. Anyone who didn't stand had to write a note explaining why not. We were also told straight away that we couldn't even mention Ukraine," says Kateryna.

"The head of security, Valery Astakhov, said they would bomb Kyiv, and Kherson would soon be Russian again. We were never given a straight answer when we asked when we would be taken home. On top of that, there were rumours that we might be put into a children’s home. That was the scariest thing," the girl adds.

Vitalii, 16, from Beryslav, went to a camp in Crimea last autumn.

"They didn’t treat us like human beings. They forced us to sing the Russian national anthem, and those who wouldn’t were taken to a separate room for a talk, threatened with being put in the basement, and told that those who were already 18 would be sent to the army, and the others would be dispersed around the Russian Federation," Vitaly recalls.

"When they brought us there, they said, 'Ukraine means terrorists, they kill people.' They’d beat us with sticks for saying 'Glory to Ukraine!' They swore at us and called us names, like Khokhols [a pejorative Russian word for Ukrainians]. When one girl hung up a flag of Ukraine in a room, they burned it," he said.

Russian officials would come regularly for inspections, and the children were forced to sing Russian songs.

"People came from Moscow and Crimea to see us, and we had to rehearse songs for them. We sang ‘Forward, Russia’ [a song by Oleg Gazmanov, released in 2015 for the 70th anniversary of the USSR’s Victory in the Second World War - ed.] and ‘The Curve of the Yellow Guitar’ [a song by Russian singer Oleg Mityaev]," says Yana, 12, who was recently brought back from Crimea.

Almost all the children who went through the Crimean camps remember Valery Astakhov, the head of the security service.

"He told us that Ukrainians are ‘pans’ and ‘Khokhols’ [both derogatory words], and that we should live by their rules and laws while we are there," says 15-year-old Taisiia, who returned from Crimea.

"I was wearing a T-shirt that said ‘Glory to Ukraine’, and the man in charge of security approached me and said: ‘Either you cut up that sweater, or you will sit in the basement until your mother comes, or you will go to Kherson with very big problems.’ It was him and two policemen. I cried and said I wouldn’t cut it up. In the end, he did it himself, with scissors," says Taisiia.

Recently, the Security Service of Ukraine announced that Astakhov had been served with a notice of suspicion in absentia. According to investigators, he is a former member of Berkut [a now-disbanded elite riot police force renowned for its brutality] and was a member of the Yevpatoriia Company of the People's Militia, which is controlled by the FSB. The investigation believes that the Russian secret services had instructed him the year before to form a group of agents to work against Ukraine.

Many children and their parents were offered the chance to stay in Crimea and promised housing and cash certificates. Some agreed to it.

"I think their logic was this: wherever the children are, the parents are there too," says Inessa, the mother of a teenager who was brought back from Crimea.

Last year Iryna, who is from the Kherson region, also sent her daughters, aged 11 and 15, to Yevpatoriia for a couple of weeks. She did not see them again for four months.

"We were told that Russian soldiers were supposed to be coming to see us and we had to write them greetings, letters, draw pictures for them," says 11-year-old Valeriia. Her sister Oleksandra recalls how the boys jokingly asked the counsellor "Who does Crimea belong to?"

"They were taken to see the director, threatened by the FSB, and told that they would be imprisoned for 15 days," she says.

The teenagers in the camps mostly resisted the Russian propaganda.

"When the Russian national anthem was playing, we’d put the Ukrainian national anthem on in our earphones and listen to that," says Vitalii, 16.

"On New Year's Day, we were shown Putin's video address and some people left the room and started shouting ‘Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!’" says 16-year-old Taisiia. She said children who disobeyed the care workers would be locked up for several days in "solitary confinement".

"It's a room with a bed. They bring you in there, take away your phone, shut the door, and you're left sitting in an empty room."

Primary school-age children, however, are very easily influenced. Those who managed to return said that many of their peers had begun to support the Russian Federation and would wear T-shirts with the letter "Z" on them.

Some did not want to return to Ukraine; some, even after returning, talked about how wonderful it was in the camp, because "the food was good and they were taken on excursions around Crimea".

"A prolonged stay in this camp is a procedure of Russification," says lawyer Myroslava Kharchenko. "The child is there without their mother, father, or family. They are in a vulnerable position."

"What are their recent memories of Ukraine associated with? Shelling, cold, death... That's why some of them don't want to go back," explains Aksana Filipishyna.

"But this is manipulation. First, they came to our land, killed their parents, bombed their homes, forced them to starve and lose everything... And then these ‘liberators’...", the human rights activist explains.

Of course, questions should also be asked of the parents who consented to their children being sent away to Russian camps. However, volunteers working in this area are convinced that most of the parents were under a lot of pressure.

"You have to understand that the parents were living under occupation, they were scared," says Olha, a spokeswoman for the Save Ukraine charity. "The Russians manipulate them, telling them that the camps are a mandatory part of the educational programme."

Education and militarisation

In schools that are currently under Russian occupation, the curriculum has been developed according to Russian standards. Russian language and history are now compulsory subjects, and Ukrainian language is optional. New classes known as "Conversations about Important Things" teach children how Russia has saved them from "Nazis". Children are also being taught that the occupied territories have always belonged to Russia.

"Ukrainian symbols have been banned. They could get you expelled or you could have criminal proceedings initiated against you. The teachers would give us unofficial warnings about this," recalls Vitalii, a 10th-grader. He spent almost a year studying in Russian-occupied Torez (Chystiakove), and has since come back to Ukraine.

Vitalii says that students were asked to do drawings and write letters to Russian soldiers, and would be given grades for this work.

Sport is another avenue through which the Russian occupation regime is attempting to influence children, with kids being encouraged to compete under the Russian flag.

Civic and military organisations comprise another key element of Russian propaganda. For example, Youth Army branches have been set up throughout the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. The Youth Army is a children and young people’s organisation for kids aged eight and over that has been created by the Russian Ministry of Defence.

Its main goals are "to augment the prestige of military service, and to preserve and multiply patriotic customs."

Nikita Nagorny is at the helm of the Youth Army, with Viktor Kaurov, a representative of the Military Fraternity veterans’ organisation, as his first deputy.

"The children there have lived amidst Russian propaganda for eight years," says human rights activist Aksana Filipishyna. "They were specifically taught to shoot, they were dressed in military uniforms, they were told Ukraine as a state was their enemy. The militarisation of children that has occurred in these last eight years is a red thread that runs through the Russian Federation’s politics, with the goal of pitting our children against their own country."

Russia has recently founded the Movement of the First, which seeks to bring all of the largest children and young people’s organisations under its aegis. Grigory Gurov, a representative of the state agency Russian Youth, heads the movement, with Russian President Vladimir Putin chairing its supervisory board. The movement’s main stated goals are education, organising leisure, and fostering a worldview "grounded in traditional Russian spiritual and moral values". Its mission is to "Be with Russia, be a human, be together, be in Rus, and be first."

Vladimir Putin recently proposed that members of the Movement of the First be called "pioneers", evoking the Soviet youth organisation.

In the unlawful self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic there is a Military Fraternity Volunteer Company, and in the Luhansk People’s Republic there are Youth Labour Squads and the Luhansk International Centre.

Several similar organisations were also established last year on the occupied territories of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, including We Are Together with Russia, the Slavic Guard, and Volunteers for Russia. A Crimea Patriot Centre has been set up in Russian-occupied Crimea.

Sergey Aksyonov, the Russian-appointed "head" of Crimea, has issued an order whose express goal is to strengthen cooperation between educational establishments and military enlistment offices.

The Russian occupation regime has enlisted representatives of these organisations to join political demonstrations, for example during Russia’s celebrations of Victory Day on 9 May, and on the day when the illegal decrees annexing the occupied territories of Ukraine to the Russian Federation were signed.

Over the course of several years, all of these events can foster real hatred towards Ukraine among Ukrainian children. The 20-year-old soldier I met at a checkpoint in Russian-occupied Donetsk last autumn is a living example of how this can happen.

He was born in Donetsk. He was 11 when the war started in 2014, just like Sashko from Mariupol. He is now sincerely convinced that he is fighting for his "motherland" and against the "Nazis". He was brought up on Russian propaganda.

"The children who were captured in 2014 are now standing there shooting at us. If you ask them, they will tell you they think that on this side we have Nazis, imbeciles, and murderers," says lawyer Myroslava Kharchenko. "The Russians honed their re-education skills on those kids. Now, it only takes them three or four months to brainwash a kid."

How can Ukraine bring back its children?

According to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, the Russians have taken at least 19,000 Ukrainian children to the Russian Federation and Russian-occupied Crimea. As of early May 2023, only 364 children have been brought back to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian government has stressed that Russia’s actions violate the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

Ukrainian government representatives’ frequent reports on the violations committed by the Russian Federation have resulted in an ICC investigation.

"But this is not a mechanism for bringing back [the children]. It is only a judgement on Putin’s actions and the actions of his allies," believes human rights advocate Aksana Filipishyna.

Whether Ukraine can bring back all of the forcibly deported children, and how soon it can do so, remains an open question. There is no fixed and lasting mechanism to make this possible.

"Since one of the sides does not abide by rules or international legal norms, no mechanism – even if one existed – could be implemented," says Daria Herasymchuk, advisor to the president on children’s issues.

According to Herasymchuk, the process of bringing back Ukrainian children is further complicated by the lack of diplomatic relations between Ukraine and the Russian Federation, and the lack of Ukrainian access to Russian territory.

The Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War bans an occupying state from transferring civilians to its territory.

"Even if such transfers take place ‘on humanitarian grounds’, it must immediately report this to the patron state and hand over all information concerning the transferred persons," Filipishyna says. "The issue, however, is the absence of a patron state – a neutral third country that both sides would trust."

Filipishyna believes that another key issue is the lack of an independent institution specialising in children’s issues in Ukraine.

"We have an advisor on children’s issues: not an [independent] ombudsperson, but a political appointee, an official in the President’s Office. The advisor acts in accordance with a presidential decree and its statute. But in situations like this, it’s independent institutions that should be doing this work," she says.

The Office of the President, however, stresses that this is not an issue, because the advisor’s office includes a representative of the Commissioner for the Rights of Children, Family, Young People and Sports, and the Department for Monitoring Compliance with Children’s Rights. Besides, a new coordination council on bringing back children has recently been formed.

Meanwhile, the search for third-country mediators continues, according to the Office of the President.

Poland is currently working with the European Commission to develop a mechanism to search for Ukrainian children and bring them back from Russia. The French Senate has called on the European Union to search for deported Ukrainian children and sanction those who were involved in their deportations.

Ukraine’s police has launched a Reunite Ukraine app to search for missing children, and to help reunite family members who have been taken to Russia, Belarus or the temporarily occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk has also said that an international coalition is currently being formed to bring back Ukrainian orphans.

Ukrainians dealing with this issue continue to hope that the mechanisms that are being developed, and that have already been launched, will speed up the process of bringing the children of the war back home.

***

Children are the future of Ukraine, which is why Russia is so persistent in its attempts to root out their love for their Motherland and make them love Russia instead.

To this end, Russia disguises its crimes as evacuation, rescue, and recovery efforts. The Russians spare no effort, money or time in their re-education of Ukrainian children. But however they refer to what they are doing, it is nothing but a crime.

This is why it is so important to make the whole world aware of these violations and to make every effort to bring Ukrainian children back home and bring the perpetrators to justice.

Translated by Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Oxana Hart, Tetiana Buchkovska, Elina Beketova and Olya Loza

Edited by Teresa Pearce