Russia's military-industrial complex is gaining momentum. Where does the money come from, and who helps Russia produce missiles?

Russia's military-industrial complex is gaining momentum. Where does the money come from, and who helps Russia produce missiles?

To thwart the aggressor, it will be necessary to hit revenues harder and cut off the "helping hand" from Russia-friendly countries and companies, including many in the EU and the US. How is the Russian military-industrial complex increasing its capacity?

For the past 15 months, Putin has been trying to convince the world that he is not at war with Ukraine; rather, he is conducting a "special military operation". Russia denies having switched to a wartime economy and pretends everything is going as planned.

However, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, the Russian invaders have been gathering all possible resources for the war and spending unprecedented amounts of money to strengthen the army.

The primary purpose of Western sanctions against Russia is to make financing the war impossible, but this has not been achieved so far. Russia continues to increase its military spending and its output of military products, and to find ways of importing banned components.

How much is Russia spending on the war?

Russia’s total spending from the federal budget in 2023 will be RUB 29 trillion (US$361 billion). A record RUB 9.4 trillion (US$117 billion) has been allocated to the army and security forces, 60% more than in 2021.

This means that every third rouble from the federal budget is being spent on the war in Ukraine or supporting the regime.

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg, as some military expenditure has been disguised as spending on education, social welfare, and support for the economy or the regions.

Take the funding of propaganda, for example. The federal budget is spending RUB 118 billion (US$941 million) on state support for the media. A further RUB 20 billion (US$159 million) will be allocated to the Internet Development Institute, an organisation that finances propaganda content.

The Russian Ministry of Education will be allocating RUB 40 billion (roughly US$319 million) to "patriotic education for young people", six times as much as in 2022.

These funds will be given to organisations that promote Russian ideology to school-age children. One of them, the Movement of the First, will be operating in the Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia.

Through economic support programmes, the Russian budget will allocate over RUB 200 billion (US$1.6 billion) to the state space corporation Roscosmos, which is effectively part of the Russian military-industrial complex. Roscosmos produces military satellites and supports the GLONASS navigation system, which is used to guide missiles, and has its own armed formations.

Public money intended for Russia’s regions has also been mobilised for the war. About RUB 550 billion (US$4.39 billion) in subsidies will be allocated to the occupying administrations in the Russian-captured parts of Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. The collaborators will spend these funds at their discretion.

Local budgets across Russia have partially borne the social costs of the military. The regions pay RUB 1-3 million (roughly US$8,000-24,000) out of their own pockets to families for each occupier from their region who is killed.

Some social welfare payments, such as monthly pensions for disabled veterans, will be covered by the all-Russian state-sponsored Social Fund.

See also: "Safe havens" for blood money. Why are Russia's assets not being seized in the West?

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the military expenditure for which the Russian budget has found funds. Another chunk of the money has been mobilised from the accounts of private and state-owned companies.

A BBC investigation revealed that the state-owned energy corporation Gazprom recruited its security guards for the war and used them to form the Potok, Redut and Fakel units. Likewise, Roscosmos enlists employees into its own battalion, named Uran.

The Akhmat Kadyrov Foundation, which supplies personnel to Chechen "military volunteer groups", is funded by levies on businesses. Local businessmen also support the "private military company" of Sergey Aksyonov, the Russian-appointed head of temporarily occupied Crimea.

Where has all this money come from?

The increased military spending could have led to significant cuts in other programmes and disrupted the economy, but Moscow has managed to avoid this so far.

Although federal budget expenditure does exceed income, the shortfall is insignificant. The gaps are covered by the "war chest" - the National Wealth Fund (NWF). It now holds RUB 12 trillion (US$95.7 billion) in its accounts, which the Kremlin has been amassing from excess oil revenues in recent years.

The Russian government has also been able to acquire more money by borrowing roubles from its citizens and banks and raising taxes on businesses.

The Kremlin raised the tax on mineral extraction in 2022. The Russian budget will receive an additional RUB 1 trillion (US$7.97 billion) from gas, oil and coal companies alone in 2023.

See also: US$20 billion for Putin. Why Western countries hesitate to impose sanctions on Russian metals and diamonds

The belt-tightening will also affect other large businesses.

The Russian Ministry of Finance plans to introduce a windfall tax on private companies’ profits, which will contribute another RUB 300 billion (US$2.39 billion) to the budget. The government will also raise excise duty on tobacco products, gaining an additional RUB 100 billion (US$797.8 million).

The tax authorities are getting tougher about "shaking down" businesses to meet military needs. The number of "tax claims" has increased by 80% since 2021.

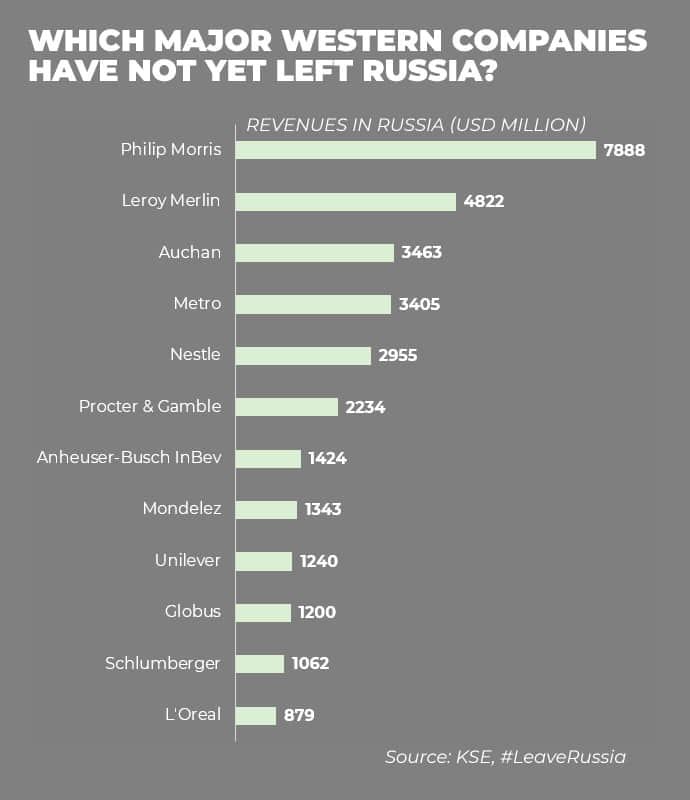

The tax frenzy has also affected Western companies that still operate in Russia. The Russian authorities have accused the French companies Auchan, Leroy Merlin and Decathlon of tax evasion and are preparing for inspections.

Overall, there are still about a thousand Western companies in Russia.

They continue to operate in Russia, earning tens of billions of dollars in revenue and paying taxes to the federal budget, which is spending increasingly more money on the war and less on social programmes and development.

The draft proposals for the 11th EU sanctions package included an idea to incentivise Western companies to leave the Russian market, but it has not yet garnered sufficient support.

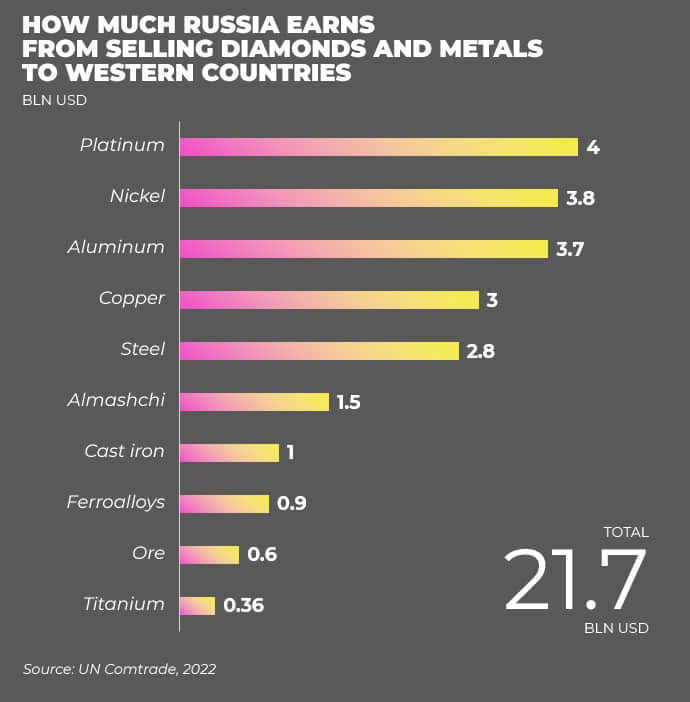

Another "Western" source of replenishment for the aggressor's military budget is conventional trade. The sanctions regime allows Russian companies to sell certain goods to the US, EU and UK and increase their profits.

Russia earned US$20 billion from exports of metals and diamonds to Western countries in 2022 alone - and the aggressor continues to generate revenue because these goods have not been banned.

The technology embargo is still full of holes

Raising a few trillion dollars is only half the story. Russia needs access to Western electronics to wage war. Otherwise, producing modern Russian missiles, aircraft, drones, radars and tanks is impossible.

Western countries have not been able to completely cut off Russia's access to their technological components over the past year. There are still ways to circumvent the embargo - enough to manufacture certain equipment.

The first way is legal. The Russians get some electronics by disassembling household appliances. Ukrainians have already found parts from refrigerators and industrial equipment in Russian tanks.

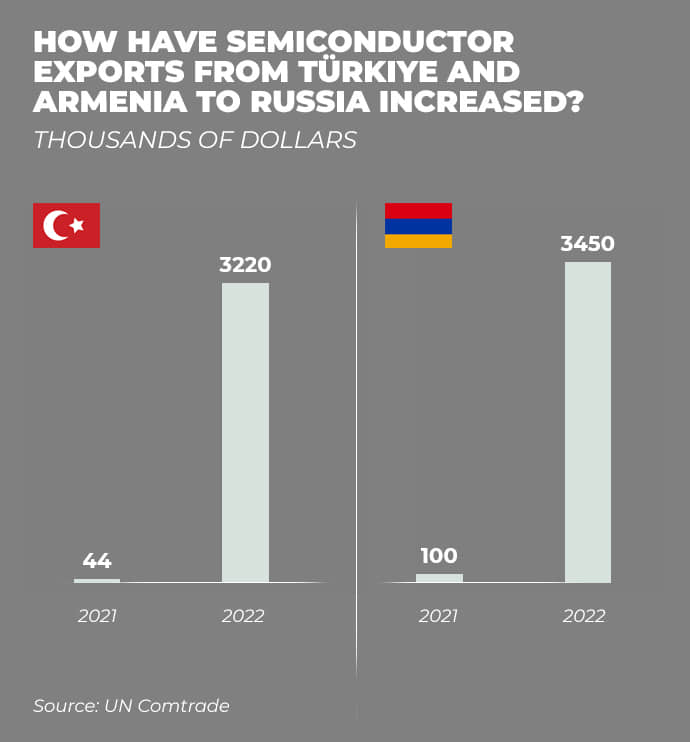

The second way is semi-legal. Deliveries to the Russian Federation take place through neutral countries. It isn’t hard to figure out which ones.

Semiconductor exports to Russia from Türkiye, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Serbia have increased tenfold. None of these countries are manufacturers of microchips. They play the role of intermediaries.

It is difficult to control the resale of critical components because it is impossible to determine the end user. Moreover, depending on the level of technology control, the Russians cover their tracks in every possible way.

Mykhailo Honchar, President of the Strategy XXI Centre, described how together with the Institute of Black Sea Strategic Studies, they tracked some EU citizens with Russian surnames as they set up a company in Switzerland, re-registered it in Silicon Valley, then founded a joint venture with the defence company EDGE in the United Arab Emirates.

This new business is engaged in the development of drones and anti-drone technologies. In this way, the company's senior management, with its Russian and Belarusian roots, gained completely legal access to critical components from Western countries and the theoretical possibility of sending them to Russia via the UAE.

As a last resort, there is an entirely illegal way. Since 2012, the United States has seen dozens of high-profile trials of Russian agents involved in smuggling tens of millions of dollars’ worth of goods for the Russian military-industrial complex.

Catching Russian agents in the West has become more common since the full-scale invasion.

One FSB-controlled network exported 22 tonnes of German equipment. Another was shipping microprocessors for satellites and rockets to Russia through shell companies in Germany and the UAE. Smugglers have also been caught in Estonia trying to smuggle 20 boxes of American sniper rifle cartridges.

And this is far from a complete list of the high-profile cases in 2022. The big question is what to do about all this.

"Trying to sanction individual companies is like dealing with Horynych the Snake - as soon as you cut off one head, three grow in its place," Olena Yurchenko, adviser to the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, told Ekonomichna Pravda. "Shell companies appear in droves daily, and the space for such activity cannot be closed off.

The idea of allowlists and blocklists of companies with which operations can or cannot be conducted will not work either. Only a complete ban on the export and re-export of these goods to Russia will have an effect."

Ukraine is proposing that the list of prohibited goods in Western countries be standardised. As Vladyslav Vlasiuk, an advisor to the Office of the President, explained to Ekonomichna Pravda, the lists of dual-use goods in the EU and the US are different. Some items that the United States has banned may be permitted for export from the European Union, and vice versa.

The Russian military-industrial complex is still alive and kicking

The introduction of sanctions has made it more complex and more expensive for the Russians to produce military equipment. The capabilities of the Russian military-industrial complex are not sufficient to bring the army's equipment back up even to the level of 24 February 2022: the demothballing of 70-year-old Soviet T-55 tanks is evidence of that.

The Ukrainian army destroys Russia’s equipment faster than it has time to build it. At the same time, sanctions have not spelled disaster for the Russian defence industry. The trillions of roubles of budget allocations and embargo loopholes are enough to support production and keep the war going.

Data from Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence indicates that the Russians, under sanctions, were able to build more than 500 cruise missiles during the year of the full-scale war.

"The Russians need Western technology mostly for high-precision weapons and equipment," said Archil Tsintsadze, a defence expert and former Georgian military attaché to the United States. "For more primitive weapons or defensive equipment, such as shells and artillery, Russia has always had a full production cycle."

The fact that the Russian military-industrial complex is "alive and kicking" can also be seen from official Russian statistics, noted Lidia Lisovska, an analyst working on the ANTS project "russian Assets as a Source for the Recovery of the Ukrainian Economy".

According to Lisovska, in the first quarter of 2023, the production of binoculars, monoculars and other optical devices in Russia increased by 73% compared to the same figures in 2022. The production of radar, radio navigation products, remote control equipment, computers, electric motors, generators, batteries, and special clothing and footwear rose by 40-110%.

This may indicate the replacement of products previously imported from Western countries and an increase in production for the army.

Other indirect indicators testify to the growth of military production. A factory manufacturing drones in Dubna, near Moscow, has switched to work in three shifts, and the Smolensk Aviation Plant, which produces cruise missiles, plans to increase the number of employees from 2,000 to 4,300.

At the same time, some Western companies are directly helping the Russian defence industry. For example, an investigation by The Insider showed that the German companies Jakob KECK Chemie GmbH and Salamander SPS GmbH, as well as the Italian company Tacchificio Campliglionese, supply items used in the production of army boots to a Russian company, Donobuv.

Italian company Minelli Carmello has supplied machines for the production of body armour, and France’s Marchante has provided equipment to Kurganpribor, a company which produces MLRS detonators.

Western firms have often taken advantage of the fact that many Russian military enterprises did not fall under sanctions. For example, the French company Radiall S.A. supplied components to Roscosmos because the latter’s main contractor, ISS, was under US sanctions but not European ones. This continues to be a problem.

According to Ukraine’s anti-corruption agency, the NACP, the European Union has not imposed restrictions on Rosvertol (Mi-28N helicopters), the Specialist Machine-building Design Bureau, or Novator (Kalibr missiles), while the US has not sanctioned Strela (radars), the Omsk Transport Machine Factory (T-80BVM tanks), Motovilykhinskie Zavody (artillery) or Severnaya Verf (warships).

Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK also have notable shortcomings in their sanctions policies with respect to Russian businesses.

The sudden surge in the defence factories’ activity will not only arm the occupiers but could also support the Russian economy during a downturn, even if only temporarily.

"The statistics, in this case, are deceptive," said Mykhailo Honchar. "On the one hand, the Russian economy is creating new jobs and generating GDP in the defence sector. On the other hand, industries that could be making real profits are losing money and workers. The military-industrial complex mostly spends public money rather than generating new funds. During the Cold War, high military spending was one of the reasons why the USSR slowed down and disintegrated."

So, sanctions and the war are depleting the Russian economy, but only in the long run. To thwart the aggressor now, at one of the decisive moments of the war, it will be necessary to hit its revenues harder and cut off the "helping hand" from Russia-friendly countries and companies, of which there are still many even in the EU and the US.

Bohdan Miroshnychenko

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn and Yelyzaveta Khodatska

Editing: Teresa Pearce