The hunt for Russian war criminals. The year-long investigation to uncover Russian war crimes in Yahidne

This is Yahidne’s second spring since Russian occupation. Russian forces withdrew from the village on 30 March 2022, leaving behind bodies of civilians who had been shot to death, the corpses of people who had died while hiding in a basement, and a village suspended in a state of shock.

A group of investigators came to Yahidne soon after the village was liberated. Journalists followed suit, and the world learned of the horrors of the Yahidne basement.

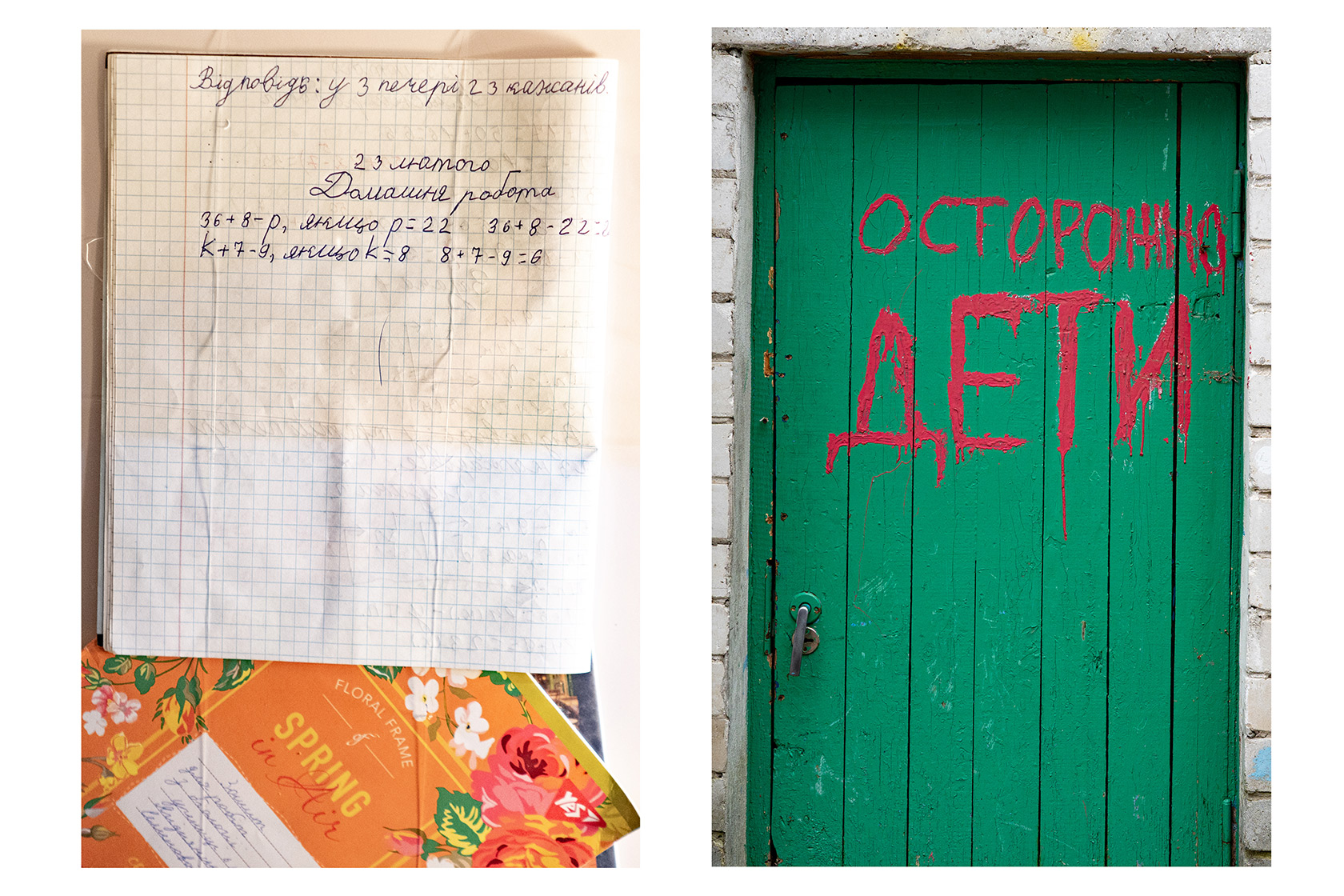

Russian forces occupied the village on 3 March 2022. They set up their headquarters in a local school and moved into the villagers’ homes. Most of the villagers were forced to stay in the school’s basement for nearly a month, until the Russians withdrew from Yahidne. Ten people died from suffocation, lack of medical treatment, and inhumane conditions.

We were part of the team – along with The Reckoning Project – that reported on the situation in Yahidne; our report was published in TIME magazine. TIME also published a Ukrainian-language version of the report, and a film about Yahidne, on their website.

In April 2023, a year after the liberation of Yahidne, I pack a stack of TIME copies and go to Yahidne to give them to people we interviewed for the report, and then to Chernihiv, to find out how the war crimes committed by Russian forces in Yahidne are being investigated.

The way into Yahidne lies along the E95 highway. Before the Russian invasion, the highway, which connects Kyiv and Chernihiv, was a place where the villagers could earn an extra buck selling fruit, saplings, and wicker baskets. Last spring, the highway – lined with cars wrecked by shelling – was a horrible sight.

A year on, things are coming to life again. Shipping containers converted into little stores stand in front of the burned-down cafe, with trucks lining up in front of them at the crack of dawn. Steam rises from cups of coffee, exhaust fumes trail from jeeps brought from Europe for the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and a fog settles over the full waters of the Desna River.

The small, grey silhouette next to a cart full of saplings is Nadiia Radchenko. She never would have thought before the invasion that this is what she'd be doing: "I wanted to rest and see some of the world after retirement." Her life is one of many that have been upended by Russia’s invasion.

Russian soldiers looted Nadiia’s house. They shot at the cellar where she and her family were hiding and put guns to their heads. Then a shell crashed into Nadiia’s yard, killing her husband and injuring several other villagers. A relative of Nadiia’s lost her daughter to the attack.

368 casualties

The three soldiers who came to the Radchenko family’s house have been sentenced in absentia to 12 years in prison for cruel treatment of civilians. Investigators found bullets, shell casings, and ammunition manufactured in Russia in 1993 stuck in the walls of Nadiia’s basement.

The death of her husband poses more questions. Serhii Krupko, a prosecutor at the Chernihiv Oblast Prosecutor’s Office, admits that it is difficult to know whether it will be possible to determine who fired that bullet and from where.

Krupko has spent the past year investigating the war crimes Russian soldiers committed in Yahidne. He keeps a backpack belonging to one of the Russians in a safe in his office; folders of victims’ statements line the top of the safe. A total of 368 people, including 69 children, spent most of March 2022 in the basement of the Yahidne school. Around 400 people lived in the village before the Russian invasion.

"Every day at work was like working in a call centre," Krupko recalls of the time he spent looking for witnesses.

The Yahidne investigations consist of several considerations. First, the fact that civilians were held in the basement of the school in inhumane conditions, effectively as a human shield. Second, the cruel treatment of civilians outside of the basement, in the village itself: before taking everyone to the school, the Russians looted people’s homes, opened fire on them, humiliated and abused people; all of these actions violate the laws and customs of war. Third, and final, are the executions of 11 men.

After the liberation of Yahidne, a group of investigators stayed in the village for a week, interviewing around 200 villagers. Their main goal was to confirm the fact that crimes had been committed, that people were indeed forcibly held in the school basement. Villagers testified that Russian troops told people they had to go into the basement "for their own good".

It’s possible that those responsible will continue to argue that villagers went to the basement voluntarily, for their own safety. This is the argument that Andrey Timoshenkov, a Russian soldier, resorted to in The Diary of a Survivor, a film by Suspilne. "No one was forced to stay there," he told a Ukrainian journalist.

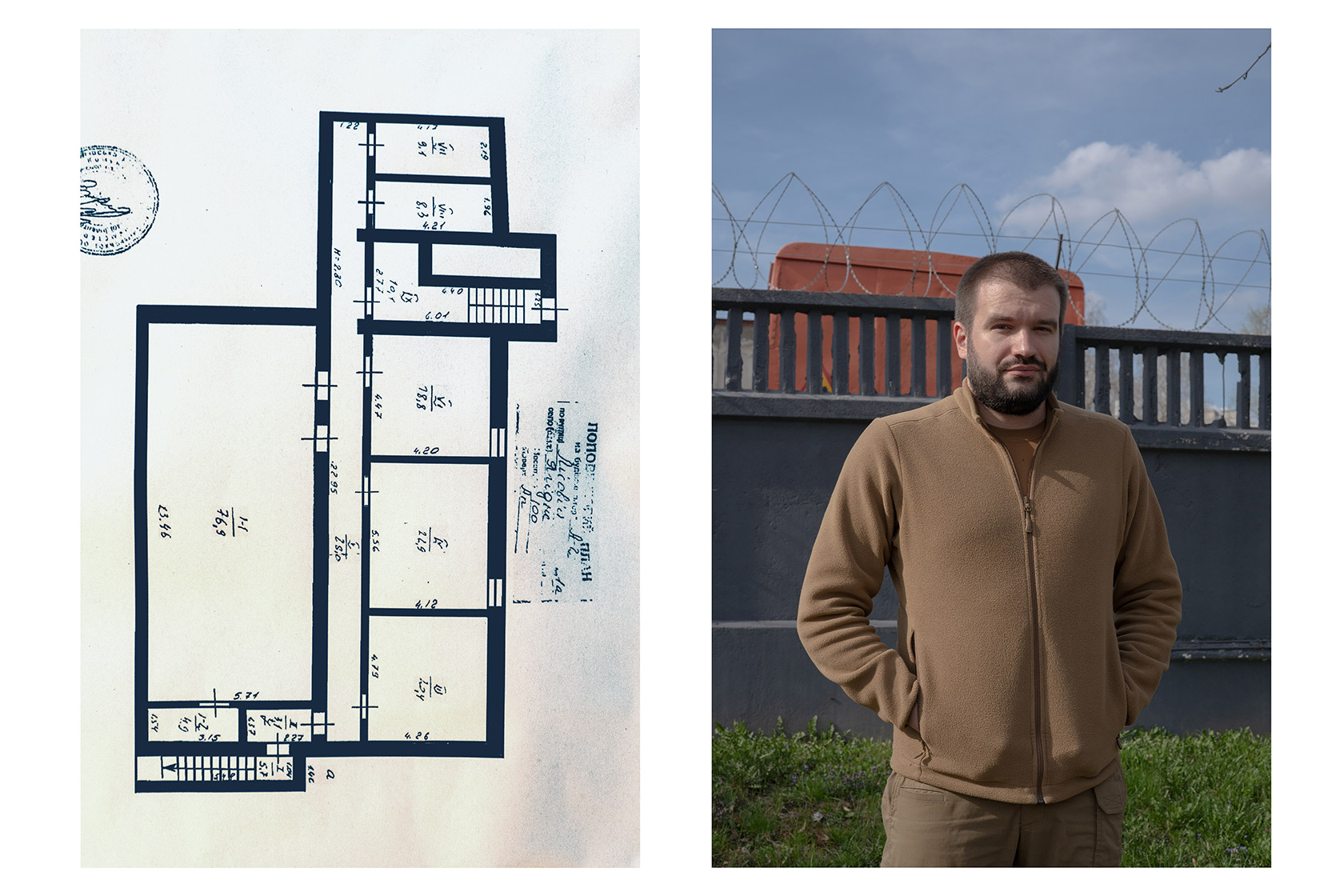

To prove that the basements of residential buildings were safer than the school basement, the investigators visited over 13 cellars in Yahidne. These were often sturdy and robust concrete-floored rooms the size of an entire house.

"Each person in the school basement had about as much room as this," Serhii Krupko points to an office chair. "Meanwhile, a family of four would have had 50 square metres to themselves in their own basement. They had food there, and stoves that would have kept them warm."

Photographs and documents

Investigators then began to examine the conditions in which people were held in the school basement. Overcrowding, suffocation, a ban on leaving the basement or taking the bodies of the dead outside, the fear of being shot or raped – the prosecutor and the investigators were deeply horrified by the villagers’ testimonies.

"A month into the war, I still couldn’t imagine something like this could happen," says Andrii Prosniak, head of the investigative department of the Security Service of Ukraine office in Chernihiv Oblast.

We are in an unmarked building (the Security Service of Ukraine office in Chernihiv Oblast was shelled on the second day of the invasion, the building burned down, and the investigators are now based in a different one). Prosniak tells us that as soon as Yahidne was liberated, the investigation team "followed the Russians’ trails". They eventually found documents that have helped determine the identities of dozens of Russian soldiers.

The majority of those documents were psychiatric records pertaining to soldiers from the military unit No. 55115 based in Kyzyl, the capital city of the republic of Tuva, Russia. Located near the Mongolian border, Tuva is the poorest Russian region and, coincidentally, the birthplace of Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu.

Photographs of Kyzyl on Google Maps show Soviet buildings and Buddhist temples. Searching for pictures of places where the soldiers who came to Yahidne are from often turns up no results. These are remote settlements amid mountains and steppe. Unsurprisingly, many of those soldiers spoke worse Russian than people who lived in Yahidne.

Psychiatric records contained colour photographs of the soldiers and their personal data, including height, weight, information about their relatives, phone numbers, and so on. Passports, military IDs, and a waybill for a MAZ truck, for the period from 27.02.22 to 1.03.22, were also found.

Investigators showed all of the photographs they found to the villagers. If they recognised individual soldiers, and testified about the crimes they committed, separate cases were opened. One soldier, for instance, led a man to a fence, interrogated him about the positions of Ukrainian forces, threw a grenade at his feet, and threatened to kill him. The man fell to the ground to protect himself, and the soldier just laughed.

"Such actions are an example of torture and cruel treatment of civilians," prosecutor Serhii Krupko says.

In cases like this, there was a victim, the perpetrators were identified, and there was evidence of the crime committed, making the cases easier to investigate than the complex case of the detention of 368 villagers. Sentences on most of these separate cases, like the Radchenko family case, have already been handed down.

15 Russian soldiers

The investigation into the case of people being held in the school basement is ongoing. As of April 2023, 15 soldiers involved had already been identified. They will be tried for forcibly taking people to the basement. The soldiers escorted villagers to the school under threat and at gunpoint, and held them there, ignoring their pleas to be released – all to use them as a human shield to protect their headquarters from the Ukrainian armed forces’ attacks. The Russians’ headquarters were located right above the basement where the civilians were held, on the two floors of the school and kindergarten.

This is how the prosecutors formulated the notices of suspicion for most of the 15 soldiers from military unit No. 55115, citing the Geneva Convention, which prohibits any use of civilians in the defence of military facilities.

Several soldiers have committed other violations of the laws and customs of war. Private Arian Hertek, who was 28 during the occupation of Yahidne, threw a smoke bomb into the basement of a private house and forcibly detained people in that same basement for several days.

Private Buyan Dadar-ool, 33, sexually harassed a woman held in the school basement.

Private Aigarim Mongush, 30, fired at houses with people inside, and pointed an assault rifle at the throat of a Yahidne resident.

Judging by their names, 14 of the soldiers were ethnic Tuvans or members of other non-Slavic ethnic groups, and one was an ethnic Slav.

According to witnesses, soldiers of Slavic background were based in the school. They were the ones responsible for detaining the villagers in its basement, creating a schedule for when people were allowed to use the toilet, and prohibiting the villagers from burying their dead.

Villagers remembered the commanders’ call-signs well: Pauk (Spider) and Klen (Maple). They testified that Klen was lower in rank than Pauk, but remembered him as being responsible for their suffering.

"He was the one who set up the concentration camp."

"He said if anyone wanted to go home to get some food, they had to sing the Russian national anthem."

"A man who had cancer asked if he could get his medicine. Klen told him to go hang himself."

These are just a few fragments of Yahidne residents’ recollections of Klen.

Neither Klen nor Pauk currently figure among the 15 suspects.

Where did Klen go?

It is difficult to establish the identities of the Russian commanders because the villagers often point to different people. Investigator Andrii Prosniak says that several suspects who could have been Klen and Pauk were identified. For now, though, there is no evidence that would establish beyond all doubt the identities of the two men.

Prosecutor Serhii Krupko says that several Russian military units were stationed in the Yahidne school, all of them part of the 41st Combined Arms Army, whose commanders, and the commanders of the units stationed in Yahidne, are responsible for what happened in the Yahidne basement. The village could only have been occupied on these commanders’ orders, and equally they are responsible for the horrors that took place there.

Serhii explains that the Russians couldn’t advance from Yahidne because if they’d made it to the highway, they’d have been crushed. That’s why they stayed in the village, concealing some of their equipment in the forest, and positioning some of it in people’s yards, and some by the school. All in violation of the rules and customs of war, which ban soldiers from positioning military equipment in or near civilian buildings.

Clearly someone made a conscious decision to hold the villagers in the basement. It’s quite impossible to unknowingly hold 350 people on the premises of your own headquarters for an entire month. Still, irrefutable evidence is needed to prove the commander’s guilt – for example, recordings of intercepted conversations or a soldier willing to confirm that an order had been given [to put the villagers in the basement and hold them there].

Serhii says that without evidence, the case would crumble even in a Ukrainian court, let alone an international court: "Our main goal is to have irrefutable evidence of their guilt. So that no one can doubt their guilt, not even the convicts themselves."

Witnesses, a year on

When the photographer and I go back to Yahidne after talking to the prosecutor and head investigator in Chernihiv, we visit the villagers whose stories were published in TIME magazine.

"Are you in Yahidne now? I want to give you a copy of the magazine," I texted one of the men who was interviewed about the basement.

"I’m not there," he wrote back. "I’m fighting."

You might expect being held in a basement for nearly a month would split a person’s life into "before" and "after". But Yahidne residents don’t feel like they've reached an "after" yet. Fourteen of them are fighting in the Ukrainian Armed Forces; and besides, they’re too close to Russia.

We visit Tamara Klymchuk in her home. Russian troops shot her son-in-law, and her house burned down in a Russian shelling. In March 2022, she stood by the entrance to the school basement and watched the flames consume her entire home, unable to do anything.

When the village was liberated, Tamara lived in a summer kitchen [these are usually makeshift structures in people’s gardens built for cooking and preserving in the summer, when there is a glut of produce - ed.]. Construction work on her house didn’t start until late December 2022. Now the house has a roof and windows, and construction workers are plastering the walls inside. Tamara’s is one of the houses whose reconstruction is funded by the Latvian government.

Tamara finds herself on the TIME cover and files the magazine away with other newspaper clippings, just as she used to collect stories about the Yahidne kindergarten. Tamara was its principal for many years.

We visit Olha Meniailo’s flat on the next street over. She took the famous photograph of the basement, which was published by many leading global media outlets. Olha also kept a diary, which featured in Suspilne’s film mentioned above.

Olha took the picture of the people in the basement after the Russian retreat, when she was able to retrieve her phone from its hiding place. It would have been impossible to take it during the occupation, because Russian soldiers confiscated or destroyed all the mobile phones they could find.

Many people remained in the basement on the first day after the Russians retreated because their homes were looted, destroyed, or otherwise rendered uninhabitable. Many also felt safer among other people than alone in their houses; they feared that the Russians might return.

Olha shared the photo on social media, alongside a brief account of what happened in Yahidne. Naturally, she became the first person journalists turned to at that time – and continue to turn to. Olha has not denied a single interview request, though she is sometimes reluctant to relive the events of that month. She says that in the beginning, she was overflowing with memories of what happened in the basement, but now she has to reach far and deep to retrieve them, which takes effort. When the journalists leave, she remains in the grip of those unwanted memories for days.

To get away from those memories, Olha often rides her bike to her place of strength: a fruit orchard. In April, the trees are blue after being treated with a pest control solution; a sprawling apricot stands in the middle of the orchard, like a mythical tree of life.

Valentyna Danilova is another Yahidne resident that journalists often visited throughout the past year. She was the woman who used a piece of charcoal to draw a calendar on the basement door and wrote the names of people who were killed next to it. Photographs of that door, and Valentyna’s writing, circulated all over the world. This spring, they were exhibited in New York, as part of an exhibition about war crimes committed by Russian forces in Ukraine.

Valentyna lists the countries where the journalists that spoke with her came from: Iraq, Japan, Norway, Germany, and France.

She warmly welcomes us, but it quickly becomes apparent that Valentyna, like others in Yahidne, has learned to value her boundaries and privacy. She doesn’t invite us into her home, but sends us a photo, which shows butterfly-shaped decorations Valentyna used to cover up traces of war on the ceiling of her apartment.

Crimes without an expiration date

Yahidne residents find little solace in the verdicts in absentia.

"Maybe it’s cruel, but it’d be better to know they were dead," Valerii Polhui says about the Russian war criminals.

Valerii had to communicate with the Russians more than anyone else held in the basement. He was fortunate enough that they didn’t know he served as a representative in the local government. The Russians saw him take charge of trying to establish some semblance of order in the basement, and appointed him to be "responsible for everyone" and mediate between the Russians and those held in the basement.

When we ask prosecutor Serhii Krupko what he can tell people who are disappointed by trials conducted in absentia, he responds with an answer that seems cut out of an epic saga: "Our courts’ verdicts are like swords hanging over the offenders. At some point the sword will fall on their shoulders and decapitate them."

Serhii adds that the investigations will help victims claim compensation in the future. As for the offenders, war crimes have no expiration date. Once convicted, they remain convicted for life.

War criminals can be tried by courts other than the Chernihiv court – courts of universal jurisdiction. A Russian war criminal can be sentenced by a court in Sweden or Germany, as has been the case with Syrian war criminals. And of course, the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The ICC launched an investigation into war crimes committed in Ukraine on 2 March 2022. In March 2023, it issued an arrest warrant for Putin and Russian Ombudsman for Children's Rights Maria Lvova-Belova for deporting Ukrainian children.

Serhii Krupko says he has submitted several reports on Yahidne to the ICC. The ICC’s Deputy Prosecutor recently visited Yahidne, descending into the now-famous basement. ICC Prosecutor and investigators are convinced: the Yahidne case is a key pillar in the prosecution of Russian leadership for aggression against Ukraine.

In May, the first court hearing for the 15 Tuvans will take place, in absentia. Investigators continue working to identify the commanders responsible for what happened in the basement in Yahidne, and to uncover details of the executions that took place in the village.

Yahidne stands as one of the most striking examples of the sadism Russian soldiers turned out to be capable of in the occupied territories of Ukraine. The memory of what happened in the village is being preserved in different ways. Several exhibitions told the story of Yahidne’s "basement of death". The regional department of culture wants to establish a museum in the local school. "The museum of our suffering," in the words of a Yahidne resident.

Someone has planted blue flowers where the body of a man shot by Russians was found.

Svitlana Oslavska, Ukrainska Pravda

Translated by Olya Loza

Edited by Sam Harvey

The article was prepared as part of the Life of the War project funded by the Public Interest Journalism Lab and the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna.