Empty streets, pools of blood and memories of a failed collaborator: life in liberated Vovchansk under constant fire

Vovchansk is a town in the Chuhuiv district of Kharkiv Oblast in Ukraine's east and a former district capital. It lies 70 km from Kharkiv and is only 5 km away from Ukraine's border with the Russian Federation.

The Russians occupied Vovchansk on the very first day of the full-scale war. In September 2022, the occupiers fled the town in a matter of hours without a fight, during a counter-offensive by the Ukrainian Armed Forces, leaving chaos and traces of war crimes behind them.

But even after liberation, Vovchansk's troubles were far from over. The Russians pound the town with constant shelling, although it has no strategic importance for them whatsoever. That means Vovchansk can't get back to normal. People are still being killed in the attacks. The town has no gas or water supply, and its banks and post offices are still closed.

Ukrainska Pravda visited the devastated town to hear from local residents about life under bombardment and occupation, their local Russian-appointed puppet leader and collaborators, and people's reluctance to leave their homes.

"We don't get many requests for evacuation," says Volodymyr Savvo, a volunteer and our driver on this trip. "Yesterday we were asking for at least one passenger so we wouldn't be coming back with an empty vehicle – no one was interested."

Volodymyr, an anaesthetist, volunteers with an NGO called Help People. The organisation organises evacuations and delivers humanitarian aid to people living in Kharkiv and the liberated towns and villages. Today Volodymyr is delivering 50 food parcels for employees of the Vovchansk machine parts factory, as well as sweets for their children.

We leave the city of Chuhuiv and drive around two destroyed bridges. We pass a roadblock with a sign that reads "Good morning, we are from Kharkiv, we process Orcs [a derogatory term for Russian soldiers – ed.] for fertiliser." We go past a dam with a boarded-up hole and several burnt-out cars.

We are driving along the picturesque Pechenizhske Reservoir. "Mines, stop" is written on one side of the fence and "Stop, mines" on the other.

After the village of Martove, the paved road comes to an end. The dirt road resembles a rollercoaster with the car bouncing on the potholes and swaying from side to side. The road is lined with ditches, cut-down tree branches and white flags reminding us of the danger of mines. The overcast weather only adds to the surrealism: it is as if we have entered another time and dimension.

"The bridge over Staryi Saltiv is damaged – this is a backup road," our driver explains. "This road was a mess after the winter, my teammate was driving here, and at one point he thought that was it. Plus, there are armoured personnel carriers and other vehicles rolling around here."

As we enter the village of Khotimlia, the 40 minutes of off-road driving comes to an end, and the car speeds up. The fields outside the window are replaced by a coniferous forest, and the weather is deteriorating – suddenly a blizzard starts. Soon we see a sign that reads "Vovchansk 1674" with a Ukrainian flag flying over it. A little further on, we see a booth with "Insurance Ukraine Russia" written on it. Someone has added the word "f*ck" and an arrow pointing to "Russia".

We stop at a battered five-storey building. The factory workers to whom Volodymyr is delivering the humanitarian aid are crowded around the building.

"These 30-40 people out of 600 [factory workers] have stayed behind to maintain the critical infrastructure of the town and the factory," Volodymyr says. "When there's an attack, they go and repair the damage."

"He was either taken to Russia or bumped off somewhere"

Vovchansk at midday looks bleak and deserted. Before the war, the town was home to about 18,000 people. Now, the local authorities estimate the population at about 4,000. But the general impression is that there’s almost no one left.

We pass a community arts centre with broken windows and some blue-and-yellow graffiti saying "Vovchansk". Outside a church, its domes pierced and the fence smashed in, we see a dilapidated armoured fighting vehicle and a vandalised police van.

Opposite the church is a police station with sandbags in the windows and the ruins of someone’s home. A little further on is a battered photo printing shop called Myr [Peace – ed.]. There is a rubbish-filled crater and broken glass beneath our feet.

We walk back the way we came. An Uragan rocket is sticking out of the pavement.

Across the street, a woman is walking through the snowstorm carrying two "food aid" loaves of bread and a newspaper with a picture of Zelenskyy on the front page.

"Every day they shell the shit out of somewhere," Olena says. "The church, that five-storey building, Kulynychi [an eatery], the shops, the community arts centre. There are strikes everywhere."

Olena survived Russian occupation and the harsh winter of 2022/2023 in her hometown

There used to be many large factories in Vovchansk, including a meat processing plant, a dairy, a shoe factory, and the machine parts factory mentioned above, where the Russian occupiers set up a torture chamber.

"They put drunks, drug addicts and anyone who served in the ATO in the torture chamber. On the plus side, everyone quit drinking," Olena smiles. "No one drank because they were afraid of being taken to the machine parts factory. Everyone was taken there with bags over their heads." [The ATO or Anti-Terrorist Operation is a term used from 2014 to 2018 by the media, the government of Ukraine and the OSCE to identify combat actions in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts against Russian military forces and pro-Russian separatists – ed.]

Olena's former partner – she broke up with him because of his alcohol abuse – went missing in May 2022. Olena went to the machine parts factory, hoping to find a trace of him there.

"They said, 'We don't have him.' But they knew about his friend with no fingers, they must have tortured him. Who can tell?" she ponders. "And we still haven't found his moped, his phone, his body, or any trace of where he might have been. Either he was taken over there [to Russia] or he was bumped off and buried somewhere."

The Russians turned the Vovchansk machine parts plant into a torture chamber

Locals fled Vovchansk both during the Russian occupation and afterwards, because of the continued bombardment and the approaching winter. Some went to Kharkiv and other Ukrainian cities, while others left for Europe and Russia. During the Ukrainian army's counter-offensive in September 2022, when the Russians were hurriedly fleeing the town, some of the locals joined them and went to Russia.

"Many people fled because they were afraid Vovchansk would be wiped off the map," Olena says. "Some left with the Russians because our guys [Ukrainian soldiers] came in and immediately 'closed the shop', and they didn't let anyone out."

Olena lives in a house rather than an apartment block. With no one left to help her, she has to chop her own firewood.

"There are no men left, they've gone off to fight," she says. "There are only a few left, and they are disabled."

Before the full-scale war, Olena worked as a domestic worker "for a nice family". Now she is unemployed.

"I'm not going anywhere else, I have everything here: a house, a vegetable garden, my preserves. I just wish the bombardment would stop," she explains. "Looting is rampant. And if I left, I'd automatically become homeless, because I'd have no home to return to."

"A woman was bringing her brother back from the morgue, and her head was blown off"

The civil defence centre where Olena just picked up her bread is located nearby. There are several bicycles parked by the entrance.

"This centre is our only link with the outside world," Olena says.

There are a lot of people inside the building – a striking contrast with the town's empty streets. The floor is covered with piles of boxes bearing the names of international funds and organisations. There are gaping holes in the roof.

"There was a strike literally on the other side of the wall of this building about a month and a half ago. We're still picking up fragments," says volunteer Zhanna Pysarenko. "This civil defence centre was always open – even during the occupation they gave out humanitarian aid, although it was from the invaders."

The centre for assistance from Ukraine began its work here on 9 November. It provides food to the locals, and there are also some second-hand clothes, mainly for children – there are still about 400 in Volchansk. "Street committees" help to organise the work.

"The people in charge make lists of residents, they come to us, and we give them food parcels and everything else that comes to us," explains Zhanna. "And then the street committees take it to their street and distribute it to people’s homes."

Zhanna has lived in Vovchansk for 30 years. Before the war she worked for the Staryi Saltiv village council. With the outbreak of hostilities, all the staff left for Kharkiv and she was the only one who stayed in Vovchansk. The Russian "administration" attempted to persuade her to work with them, but she refused – "God led me away," she says.

Nevertheless, there were plenty of collaborators among the former civil servants in Vovchansk. The town's former mayor, Anatoly Stepanets, also sided with the invaders. In June, he was served with a notice of suspicion of treason in absentia by the Kharkiv Oblast Prosecutor's Office.

"No one knows [where Stepanets is now], but we think he's in Shebekino [a border town in Belgorod Oblast, Russia – ed.]," Zhanna says. "Apparently they still continue to work from there."

During the occupation, Vovchansk was not shelled, but the locals had no certainty about the future. Some people just disappeared.

"It was not even possible to express anything pro-Ukrainian, to sing [Ukrainian] songs," Zhanna says. "People were taken away, some still can't be found. A woman I know, her son disappeared, and no one knows where he is, or whether he's still alive. Apparently he served with the ATO."

The mood in the town lifted after the liberation, Zhanna says, but soon after the Russians withdrew, they began shelling the town in revenge. The attacks only intensified over time as the Russians hit Vovchansk with artillery, mortars, and rocket strikes.

"At the beginning it [the shelling – ed.] was systematic: they’d strike between about 6 and 7 [am], then a little in the middle of the day, and then in the evening," Zhanna says. "But then they started [to attack] in broad daylight, and very heavily, with rockets."

People are killed by the Russian shelling from time to time. This happened about a month ago near the oil extraction plant, which the invaders shell regularly. Opposite the factory are the burnt-out remains of a car.

"In the middle of the day, the shelling began, and two cars were hit," Zhanna recalls. "The driver of one car escaped, but across from him, a woman was driving her brother back from the morgue – her head was torn off. There's still a pool of blood on the road. People are afraid to go there."

Zhanna can't get to work at the moment because of the blown-up bridge, so she wrote to request a temporary suspension. She receives no salary and relies on friends and acquaintances to survive.

"Actually, I'm an animal volunteer; I only stayed here for the sake of the animals," she insists. "I have 62 animals now on three streets, in various yards: some were abandoned, some were given to me by the owners when they left. We feed a lot of animals."

"They arrested him in April and beat the f**k out of him"

There is a crowd of people at the entrance to the humanitarian aid distribution point. Among them is a man with a grey beard wearing a tracksuit. He says his name is Ruslan.

"We’re waiting to unload the humanitarian aid," he says.

On 16 February, Ruslan's friend was killed during yet another shelling of the town in broad daylight. The tragedy occurred about 300-500 metres away from here.

"We were walking along, I stopped for a call of nature, and my friend kept going," Ruslan recalls. "I said, 'I'll catch up with you.' Then there was a strike, he turned round, and the second strike was right next to him, two f**king metres away. It was a mortar bomb.

I ran over to him – he was f**king lying there with a bone sticking out below the knee, bleeding. He was actually having some medical treatment for that leg – he had atherosclerosis or some shit like that.

I put a tourniquet on it and pulled it hard, and I called my sister: 'Call an ambulance.' The ambulance arrived quickly. They put him on a stretcher. I got out of the ambulance and they said, 'That's it, he's gone.' I said, 'What? He was breathing. Give him a shot of something, guys, he's in shock!' They said, 'He was killed instantly, it was convulsions'."

Not long after that, the man who was organising Ruslan's friend's funeral was killed by shelling. He was on his way to the village of Budarki when an anti-tank shell hit his Niva car.

"He and his wife were carrying diesel fuel and two cylinders. There was a direct hit," Ruslan says with feeling. "There are photos online of the wheels on one side and the roof on the other. He was burned alive in the car. And they say not all of his wife's body was recovered."

When we ask him about collaborators, Ruslan gets even angrier. Gesturing furiously, he describes how some locals sold Russian humanitarian aid with the permission of the Russians themselves.

"Humanitarian aid was coming in, the canned meat wasn't for sale, but there were people selling it at the market. Everything there was Russian," he recalls. "The Russians told them, 'Make some money and split it.' In the 90s that used to be called 'rearing a hog' [in Russian criminal slang – ed.]: they'd let them earn a buck and then take the f**king money off them. I didn't cooperate with anyone [Russian]: I've got my own life."

The Russians appointed local crime boss Dmytro Chyhrynov, known by the nickname "Chyzh", as the town's puppet leader. Together with the Russians, he robbed local businesses and raised the Russian flag in the town.

"He's a gangster, he did time twice under Article 117 [of the Criminal Code], for rape, and then he went to prison for racketeering," says Ruslan. "And six days before [the Russians came], he was released on bail of half a million [about US$17,500 at the time].

That was the first rotation – him and them practically had their tongues down each other's throats in the square. There was an unlicensed market in the square – people went out from there and collected the cash from everyone, and he split it with the Russians, with the first Russian assault brigade."

But Chyzh's "political career" ended as quickly as it had begun. After the soldiers rotated, the Russians in the "new wave" accused him of hiding the loot. Then, Ruslan says, the Russians replaced Chyhrynov with some "non-locals".

"The second lot came, busted him, and took all the cash off him," he says. "Some guys saw him at the machine parts factory – they were torturing him to find out where the gold was buried.

They busted him sometime in April, and they beat the shit out of him till August. They call it a 'phone call to Putin' – they electrocute your ears and torture you. Then they use the taser.

They say his back was burned, his ears were burned. The guys in there with him said they used to carry him in after an interrogation and he couldn't turn over, he'd piss on the bunks. They'd have to turn him over so he could go to the toilet."

Chyhrynov is now in prison – a Ukrainian one this time – charged with high treason.

The Russians also shot Serhii Piiev, the local forestry manager. Ruslan says he was one of the wealthiest people in the town.

"We still had a forest warden here, he was selling the forest – 'Drink'," he says. "He was shot with a Kalash [a Kalashnikov rifle] because he had shitloads of cash – he was one of the richest people in the town."

Ruslan also recalls another local torture chamber on the premises of the former district police station. He claims the torture there was even more brutal than at the machine parts factory.

"The guys told me, 'We're sitting in the cell, ATO fighters, and they say, "The neighbours are here" – FSB officers from the next floor'," Ruslan says. "They tortured one, he didn't confess. They took him to the toilet – it’s just a grid, and there's a toilet one metre square. They put him in there and said, 'If you sit down or leave, we'll kill the whole cell, 36 people.' And he stood there for three days."

A van bringing humanitarian aid pulls up to the back entrance of the centre. Ruslan finishes his story and goes to unload it.

"We can't do anything about the fact that rockets are coming our way"

We leave the civil defence centre and head to the other side of Vovchansk along Soborna Street, which used to be named after Lenin before decommunisation. The snowstorm is over, but there are no more people out and about than there were before.

In half an hour, all we see on Vovchansk’s central street are a couple of trucks delivering humanitarian aid and two cyclists

We pass an ancient house with broken windows that looks at least a hundred years old, then the ruins of the local branch of the State Savings Bank.

Through the broken window of a nearby house, we see a kettle on the stove and cups on the table. Shards of crockery and pieces of vinyl records lie on the windowsill.

On the other side of the street, in the school and neighbouring buildings, there are numerous traces of the Russians' former presence.

Inside the school there are "Z"s on the walls, half-eaten Russian-made food, packets of army rations, and mountains of rubbish on the floor. Between the buildings are dugouts and an upside-down car marked with a cross.

There are so many traces of the Russians left in Vovchansk that it feels as if they fled yesterday rather than six months ago

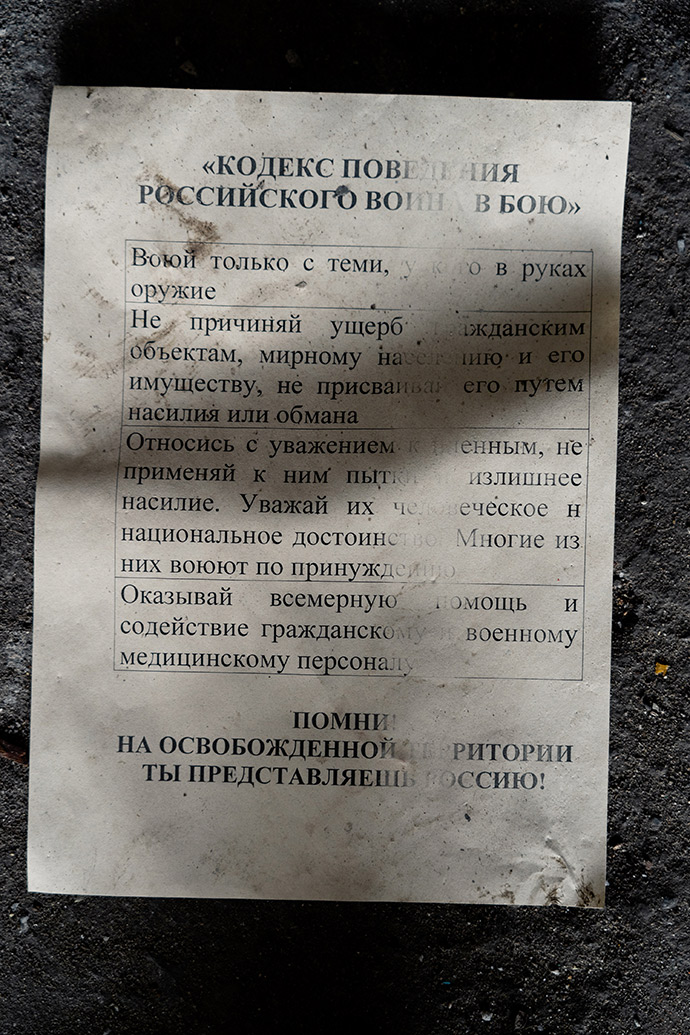

The garages have been kitted out with places to sleep, and we find a card printed with the "Code of conduct for a Russian soldier in battle", which seems a complete mockery given all the war crimes the Russians have committed in Ukraine, not to mention what the "world's second-greatest army" has continued to do to the civilian population of Vovchansk since it fled.

"The devastation is vast. It’s impossible to calculate the losses right now because the shelling is still going on, and the commission is not yet working 100%," says Tamaz Gambarashvili, head of the Vovchansk town military administration.

Vovchansk has no problems with electricity at the moment. After strikes on critical infrastructure, power engineers usually repair the system as quickly as possible. With other utilities, the situation is more complicated.

"The water situation is worse: there's no gas, and almost all our boiler houses [in the district heating system] have been turned off," Gambarashvili explains. "In winter, the system froze, people left the water on in their homes when they fled, and the pipes were damaged by the frost, so the water supply network is in urgent need of repair."

The town has mobile coverage, although residents say it recently went down for a week. Small shops open their doors when there is no shelling. No banks are open, even terminals do not work, and the postal services (Ukrposhta and Nova Poshta) have yet to resume operations.

However, according to the head of the local administration, with the arrival of spring, people are nonetheless gradually returning to Vovchansk: "A small percentage, but the trend is already apparent."

Now, Gambarashvili says, the border town is ready for whatever Russia does next.

"Our military is on duty, we are always in touch," he assures us. "But we can't do anything about the fact that shells, artillery and rockets are coming our way."

Dmytro Kuzubov. Photographs by Pavlo Dorohoi

Translation: Oxana Hart, Theodore Holmes, Yulia Kravchenko

Editing: Teresa Pearce