Those who save us from darkness. Stories of power engineers killed by Russian aggression

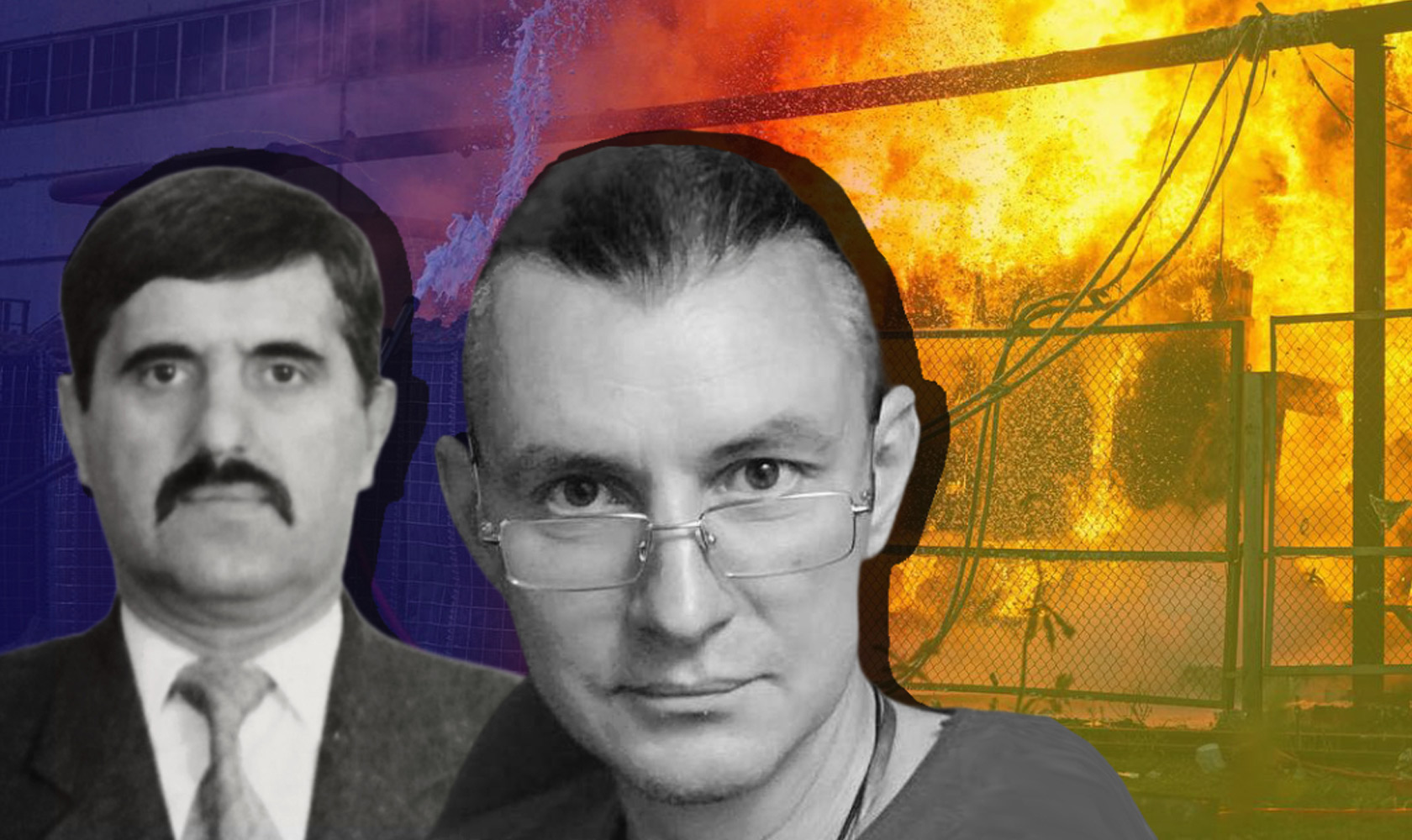

On 18 October 2022, the Russian military once again attacked Ukraine's energy infrastructure. On that day, Mykola Sakhno and Oleksii Chernykov, power engineers of the Kyivteploenergo utility company [provider of heating and hot water services for residents and facilities in Kyiv – ed.], were killed on the job.

Mykola has devoted 35 years to working in the energy sector, while Oleksii had 4 years under his belt. They both were high-level professionals. And for their families, they were a true light. Kind, caring, and calm.

We would like to tell you the stories of Mykola and Oleksii.

Mykola. In 38 years of marriage, he has never quarrelled with his wife

Mykola Sakhno turned 64 on 8 October. He was born in the village of Syniava in Kyiv Oblast. He joined the army after leaving high school. He studied agronomy in the city of Galich in Russia. Once he completed his studies, he returned to Kyiv Oblast and worked at the Rokytne Sugar Factory. After getting married, he moved to Ukraine’s capital and participated in the construction of the Metro, and later started working as a power engineer.

|

| Mykola Sakhno, 1980, photo from the family archive |

"Mykola and I had been married for 38 years; we knew each other since childhood. He was my neighbour, classmate, and friend. We even have the same surname, as is often the case in villages", says his widow, Nadiia Sakhno, adding "We have never quarrelled throughout our marriage. We were together everywhere. We were called a sweet couple. He was so kind that my family loved him even more than me. Our neighbour once said that Kolya [diminutive of Mykola – ed.] would never hurt a soul."

Mykola used to be a socialite in his youth, but after he got married, he started to devote all his time to his home, his wife and their son Roman.

|

| Mykola Sakhno with his wife Nadiia and son Roman, 1990, photo from the family archive |

He knew how to do all kinds of household chores. He fixed up the apartment himself, made furniture, and could repair anything. The neighbours jokingly called Mykola an "ambulance." His colleagues said, "No matter what happened, Mykola would come with his suitcase and fix everything."

"I have never vacuumed the house, never turned on the meat grinder, never chopped any salad, rarely washed the dishes, because Mykola was on it. I could get carried away with embroidery or knitting and not cook anything, and he never reproached me for it. When I came home from work, he would just ask if there was anything to eat at home or if he needed to buy anything. If he knew that I liked a particular cake, he would bring it every day," says Nadiia Sakhno.

Mykola was stubborn, so his wife knew when there was no point in trying to persuade him and would back down. His colleagues also recall this trait.

The man had no bad habits. He was an intellectual. He loved to read, and often did so with his son. If he took on a difficult task, he could spend hours studying the instructions and looking for solutions until he achieved the desired result.

He dreamed of a house in the countryside. He had a small plot of land where he grew tomatoes and raspberries. He loved the forest. Every year he would plant chestnuts there.

"Dad was an incredible man. He spent a lot of time with me. When I was a child, we often went to the forest with him. We would roast bread and bacon on the fire. Sometimes, we would walk 20 kilometres, just hanging out together."

He taught me how to fish, play soccer, ride a bike, ski, and skate. Dad never shouted, he was always calm. He had a British sense of humour: you could not understand his jokes by his intonation or facial expression, but only by thinking about what he said. He didn't constrain you, so it was easy to work with him. He helped me find the answer to any question," recalls his son Roman Sakhno.

|

| Mykola Sakhno's son, granddaughter and wife, 2016, photo from the family archive |

Roman says that in kindergarten, people thought he didn't have a mother because it was always his father who brought him and picked him up. Even in hard times, his father tried to buy his son everything he wanted. He treated his daughter-in-law like his own daughter. He was a caring grandfather to his granddaughter Mariia.

|

| Mykola’s daughter-in-law, Oksana, with his granddaughter Mariia, 2019, photo from the family archive |

If he had to work at night, he would just get dressed and go

As his widow says, Mykola Sakhno started to work as a power engineer when he moved to Kyiv, because he "did not have a city profession." So, he graduated from vocational school No. 4 in the capital and received a degree in electrical engineering as a category 3 power engineer.

Mykola worked at Kyivteploenergo for 35 years. Only the departments where he was assigned, and his duties, would sometimes change.

In the final years of his life, Mykola Sakhno worked at one of the company's combined heat and power plants (CHPP). He was an engineer of the 6th category, tasked with repairing the power system protection. He was responsible for an important area. Power system protection is the "brain" of the plant, which controls all of the processes. The combined heat and power plant cannot operate without it.

His son says that Mykola treated his work with a great sense of responsibility: "There was no such thing as not picking up the phone after hours or ignoring the requests of colleagues. Even in pre-war times, dad had to go to work at night. He would calmly get up, get dressed and go to help his colleagues."

Mykola worked with high voltage, but he never told his family about the difficulties involved, so that they would not worry. He always repeated that everything was fine at work.

|

| Mykola Sakhno at work, 2018, photo from the family archive |

"Mykola Sakhno was a good power engineer. He did not spend much time with friends at work. He was on his own. He missed all the team events. He was a family man, always rushing home after his shift", says Volodymyr Buhera, a colleague of Mykola.

Borys Bohdanov, Mykola’s colleague, knew the power engineer the best. They were friends for 27 years.

"Mykola was the one who hired me in 1995. He was my first mentor. Hands of gold. His work was always of high quality and he performed it very responsibly. In his last position, he adjusted relays, but in addition he was an excellent installer, welder and electric fitter. A true all-rounder. There will be no one else like him, Mykola knew how to do everything with his hands, had a sharp mind and high motivation", says Borys.

The power engineer even assisted people from other departments, who used to come to him for consultations every day. The man helped everyone. All the department heads wanted Mykola to work for them. There even was an unspoken competition for him at the company.

"Kolya was a pensioner. He had the option to stop working, but he did not quit. When Kyiv was under attack, Kolya packed his work bag as calmly as before. He took a snack and a change of clothes with him. He went to work in the morning, and it was always unclear when he would return. After the beginning of the war, he had more shifts", recalls Mykola’s widow.

The morgue workers were crying every time we came

Shortly before his death, Mykola said repeatedly to his wife: "I am so afraid to leave you alone." He had never said such things before. Nadiia had no premonitions.

On 18 October 2022, an air-raid alert sounded from 6:25 am to 10:00 am in the capital. As usual, Mykola was at work in the morning.

News of missile strikes at the thermal power plant began to emerge after 9:00. Nadiia saw the first messages in Viber chats, but did not respond to them, because she believed that her husband was hiding.

She started to worry when she couldn't get through to Mykola. The phone was still ringing, but he did not pick up the phone and did not call back. At first the company reported that there were no losses.

"I was calm until about 3:00 pm. Then I started to get nervous: the air-raid alert had long since ended, and there was no contact with my father. I suggested to my mother that I would go there by taxi. She said: ‘I'll cook borscht and leave.’ When I called again, the neighbour picked up the phone, and my mother was screaming in the background...", the son recalls.

When Nadiia Sakhno arrived at the power station, none of the workers came out to see her. They called later.

"I still remember the voice that said my husband was dead. I hear it all the time", says the widow.

Mykola Sakhno entered the morgue as an unidentified person, because his body was completely burned. His son went for the identification. Somehow Nadiia spurted out: "Maybe it wasn't Kolya?"

To which Roman replied: "I recognise dad even in the form of an ember."

"Later, we returned to the morgue several times because there had been a mistake in the documents. When the morgue workers saw me, they cried every time. It was touching, because you would expect people who see the dead every day to be used to it," the widow shares.

Nadiia did not see her husband after his death. The power engineer was buried in a closed coffin. She asked her son to describe what Mykola looked like after the fire. He replied: "I will never tell you that."

At the company, relatives were informed that Mykola was killed when the missile struck. The same cause of the tragedy death was mentioned in response to the request for information.

|

| The fire at the power plant after the missile attack, 18 October 2022. Photo by the State Emergency Service |

A fellow power engineer, Borys Bohdanov, said that the missiles hit the premises where Mykola Sakhno and Oleksii Chernykov were working. At first they were in the shelter, but soon Borys no longer saw Mykola and Oleksii there.

"A concrete slab fell on Mykola, then a fire broke out. Colleagues said that at first he gestured that he should be pulled out. But how to do so? Just yank him out of there? He was stuck between iron and concrete. Mykola was already dead when I saw him as the rescuers reached him; his body was lowered from the second floor to the ground," says Borys Bohdanov.

Oleksii Chernykov was found a few hours later under the rubble. His body was not burned.

A special commission headed by Roman Semchuk, head of the Central Interregional Department of State Labour, was set up at the company to investigate the tragedy. Members of the commission will not comment on the situation until this process is completed.

Investigators with the Security Service of Ukraine opened criminal proceedings because of the Russian missile attack on the facilities. An attack on a civilian facility is an outrageous violation of the laws and customs of war.

There will be no one else like him

Mykola Sakhno was buried at the Lisove Cemetery in Kyiv. Many people came to say farewell to the power engineer. Not only neighbours, relatives and colleagues, but also friends of his son, Roman, remembered the man with kind words. In their memory, Mykola remained the one who "never yelled at children", no matter what they did.

"It was so hard for me after the death of the guys that I couldn't go to the funeral. Mykola and Lyokha [Oleksii Chernykov - ed.] were highly valued. Without them, it's hard for the whole team. There will be no one else like them. It's like taking two aces from a deck of cards", says Borys Bohdanov. The missile attack destroyed what we had been developing for years. It destroyed lines and terminals, broke cables and foundation supports... It takes a long time to restore everything. Moreover, you don’t know what comes next. We work, and then work some more, and then another strike comes and everything has to be rebuilt from the bottom up again".

"I was told that I should not cry, so that it would be easier for a deceased person to leave this world. That is why I held back both at the funeral and at home. I started crying only once 40 days had passed. I want to scream at nights. It is very difficult without Mykola", says his widow Nadiia. "We used to be able to sit next to each other and not talk about anything and not feel tense. Now I miss his silence and his conversations. I talk to his photo."

Nadiia Sakhno stayed with a friend during the first days after the tragedy. Then she returned to her apartment. She feels better at home. She feels more lonely among people. Nadiia was not able to do anything at first. But she started to do household chores and took up knitting again a month later.

"The pain does not go away. Time does not heal. You just get used to living in a different way. I have become more vulnerable. When I watch the news, I cry for each person killed as if it were my own relative. I have only one question in my head: why did they kill my Kolya? He was someone who gave people light throughout his life. The only thing that makes me happy is the fact that Kolya was not sick and did not live in anticipation of death. He had eye surgery in the autumn. Now he is an angel in heaven with the best eyesight", says Nadiia.

|

| Mykola Sakhno with his granddaughter, photo from the family archive |

His son, Roman, misses his dad terribly. He regrets that he never fulfilled his father’s dream of visiting Greece.

"Sometimes I feel sad. I can’t believe that my dad is dead", says Roman. "It feels like he is always next to me. I feel his presence. When he was around, he was very silent, so it is easy to imagine that."

|

| Mykola Sakhno’s grave, 2022, photo from the family archive |

The family has not yet told seven-year-old granddaughter Masha about her grandfather's death. They were afraid to hurt her. The girl loved him very much. Nadiia brings her gifts and says that they are from her grandfather. "He went to work", they answer, when Masha asks why he does not come.

Oleksii. "He was very smart. A walking Wikipedia"

Oleksii Chernykov was 52 years old. He was born in the city of Kamyshlov in Russia. Oleksii’s family moved to the city of Kamianka-Dniprovska in Zaporizhzhia Oblast (Ukraine) when he turned 12. He finished school there. He communicated mainly in Russian, but he also learned Ukrainian. He had Ukrainian citizenship.

|

| Oleksii Chernykov, photo from the family archive |

Oleksii studied solid-state physics at Zaporizhzhia National University. There he met his future wife, Uliana. The girl was a year older, but fell so deeply in love that she "cheated to get into his group".

"He overturned my preconceptions. I always thought that boys who are good students cannot do anything with their hands. But he could hang wallpaper, repair a bedside table, and make something with his own hands", says his wife, Uliana Chernykova.

|

| Oleksii Chernykov with his wife, photo from the family archive |

While at school, Oleksii invented a device for a teacher that helped record exam results. The device had lights and numbers that corresponded to the grading scale. Later, he built a computer. He redesigned their clock in such a way that the TV automatically turned on after the morning alarm clock. He could easily figure out what was wrong when the refrigerator or laptop broke down, and was able to fix it.

Oleksii knew how to sew. He knitted a little suit for his daughter Yuliia, when she was born. The widow remembers it like this: "Imagine the picture. 1991, Oleksii is sitting in the park on a bench, a baby is in a stroller, and he is knitting. It was something unique."

Relatives remember Oleksii as a kind, calm, honest, and positive person. He had no conflicts with anyone, but solved problems by discussion. He was a caring man, but even before their wedding, he told his wife: "Mom will be my first priority". Throughout his life, Oleksii called her every day after work and could chatter for an hour and a half.

"Oleksii and I were like one. There was a strong connection between us, which became stronger over the years. Oleksii said that we were drawn to each other like a magnet. He could tell when I was angry by my breathing, and I could feel his mood in the voice. It was so interesting to spend time with him that even in adulthood we could talk about any topic until the morning", the widow tells us.

The man had a warm relationship with his daughters, Yuliia and Tetiana; he could talk with them about everything, ranging from first love to school worries. He gave them freedom of choice. He was very happy when his grandson was born. He was waiting for him to grow up to make things with him.

|

| Oleksii's family, 2021, photo from the family archive |

Oleksii had his own clothing style: he wore black jeans and a T-shirt or hoodie. He wore combat boots in both winter and summer. He shaved part of his head, and gathered the rest of his hair into a ponytail. He often wore headphones and listened to audiobooks. He also had many electronic and paper books. He liked to play computer games and watch Formula 1.

"Dad was very smart. A walking Wikipedia. Grandma said that he learned to read at the age of three. He gathered children around him in kindergarten and read them fairy tales. He was nicknamed ‘Erudite’ at school and university. He could talk about anything, and if he did not know something, he began to research. He never took any pills until he had studied what the active ingredient was and how it worked", recalls his daughter Yuliia Kovalchuk.

|

| The wedding of his daughter Yuliia, photo from the family archive |

Oleksii watched news from different media outlets, both Ukrainian and foreign, and compared how journalists present information about the same event.

Svitlana Kovalchuk, the mother-in-law of Oleksii’s daughter, recalled that Oleksii researched who Hnat Khotkevych was when a street was renamed in honour of the writer.

"He had no regard for a person’s position; he saw everybody as a human being first. He was a minimalist. He didn't make any claims against anyone. You always felt comfortable with him. There are only a few such people", Svitlana Kovalchuk added.

Performed work that others refused to do

Oleksii Chernykov worked for 10 years at Ukrtelecom in Kamianka-Dniprovska. During this time, he developed many programmes that helped the company develop.

In 2000, Oleksii and his family moved to Kyiv. In the capital, he worked various jobs. At first, he repaired slot machines and later, at another company, toys, and still later made LED lighting devices.

A friend suggested that he go to work at Kyivteploenergo. At first, Oleksii did not want to; he thought that he would not be able to cope. He told his family: "I don't know much about energy." His wife reassured him: "You underestimate yourself. You'll deal with everything. I know you."

And so it was. The man quickly mastered what was for him a new field. Over time, it was no longer he who asked his colleagues for advice, but they asked him.

Oleksii was an electrical engineer in the first category. He worked with relay protection and monitored the systems that ensured the functioning of the station.

"He was an intellectual and understood systems. If he didn't know something, he found the answer the next day. He didn't shy away from work. There were high hopes in him. He was not a careerist; he was not eager for leadership positions. He helped everyone who needed help. Even when someone needed him to repair something at their home, he never refused. He was modest. The team was drawn to him", recalls a friend and colleague Volodymyr Buhera.

Bubera recounts that Oleksii never argued with anyone. During disputes, he would give in so as not to provoke a conflict.

"Liokha [nickname for Oleksii - ed.] delved into every detail. He could safely perform boring and painstaking tasks that no one else wanted to do. He repaired a lot of things at the station that hadn’t worked for several years.", says his colleague Serhii Kovalchuk.

Oleksii rarely talked about work at home. His principle was not to bring work home, nor his home life to work.

"If you are destined to die from a rocket, it will fly straight to the head"

Colleagues say that since the beginning of the full-scale war, the amount of work has not changed significantly. There were just more shifts, and he had to stay at work at night more often. Difficulties arose after Russian missiles struck the thermal power plant.

"On the night before my dad died, I had a fight with him because he didn't go down to the shelter during air-raid sirens. I stressed that the CHPP is a critical infrastructure, so you should definitely go to a bomb shelter, recalls his daughter Yulia. But he replied, " I need to look after the instruments. I'm a fatalist. If I am destined to die from a rocket, it will fly straight to my head."

The next day, 18 October, a Russian missile hit his workplace.

"We live near the station. After the explosions, the lights went out, so I immediately knew where the strike was. I called my dad, but he didn't pick up the phone. My husband also works there. I didn't get through to him until after the air-raid siren ended. He said that the shelling caused slabs to collapse, there was a fire, and they are looking for dad under the rubble. His body was taken out around 14:00", recalls Yulia Kovalchuk.

"When I saw him being pulled out of the ruins, I cried. Now, when I look at that place, everything is in front of my eyes. It's impossible to forget", recalls colleague Volodymyr Buhera.

Oleksii’s wife Uliana was informed of her husband's death by Oleksii's brother. At that time, she was in Koziatyn, in Vinnytsia Oblast. She has lived there for the past few years, as she was caring for her sick mother.

"Apparently, death came very quickly because I didn't feel anything that day", Uliana says. I was working as a letter carrier and I was just on my way to the post office. After receiving news of his death, I couldn't do anything anymore."

Oleksii Chernykov was cremated and buried in Koziatyn. The funeral was attended by colleagues from Kyivteploenergo as well as by people with whom Oleksii had worked in previous jobs. Remembering the man, they cried and laughed, because there were a lot of great memories of him.

"He could have done a lot more"

Oleksii Chernykov's mother and sister are in Kamianka-Dniprovska, temporarily occupied by the Russians, but a way was found to convey news of his death to them.

The sudden death of the power engineer shocked the family. During the first month, the family could not recover from grief. To ease the pain, they began to communicate more with each other. My daughter Yulia goes to a psychologist for help.

"Dad had a lively mind. He could do much more. This is a great loss for the family and for humanity", says Yulia Kovalchuk.

She often dreams about her father. She checks if his hands are cold. She asks how he is, and he answers something with scientific words and then disappears.

His widow Uliana says she tries to think only about the good things that give her the strength to live on, because her husband loved life and did not want people to grieve for him.

"I remember Oleksii every day. Our daughter handed me the blanket that had covered him. Every time I wrap myself up in it, I think that it is my beloved who is hugging me. I understand that Liosha is not here, but it feels like he is somewhere nearby", she admits.

"His colleagues miss him", says power engineer Serhii Kovalchuk. On the team, you can often hear the words: "if Oleksii was there, it would be easier for us. If he had been here, he would have done it."

Natalia Khvesyk, special report for UP. Zhyttia

Text prepared by the memory platform Memorial, which tells the stories of civilians killed by Russia and of the Ukrainian soldiers killed. To report data on Ukraine's losses, fill in the forms: for fallen soldiers and civilian casualties.

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn, Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Tetiana Buchkovska, Theodore Holmes

Editing: Monica Sandor

Journalists fight on their own frontline. Support Ukrainska Pravda or become our patron!