An "orchestra" of murderers: Who are the Wagner Group mercenaries fighting against Ukraine?

Until recently, the Wagner Private Military Company was one of the most obscure security agencies in Russia. Independent journalists have regularly mentioned it, but the Russian authorities have kept silent.

The Russian secret services set up this private military company (PMC) in 2014. It is subordinate to Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is close to Vladimir Putin. Prigozhin denied this for many years, and it was not until 2022 that he admitted for the first time that he is indeed behind the Wagner Group.

The secret services are now trying to turn the PMC into a military brand - an "orchestra" and "musicians" – promoting membership of the Group, making films about mercenaries and dedicating songs to them.

During those eight years, the Russian secret services have involved Wagnerites in combat actions in Syria, Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Madagascar and Ukraine. They have committed numerous war crimes, including many in our state, Ukraine. For instance, they were behind the shooting down of the Il-76 military transportation aircraft in June 2014 and the killing of 49 Ukrainian paratroopers then.

An attempt by Ukraine to hold some of the mercenaries accountable in summer 2020 was unsuccessful. The authorities in Belarus, where the Wagnerites were detained, extradited them to Russia.

This caused a huge row in Ukraine at the time. The leadership of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence accused Andrii Yermak, Head of the President’s Office, of disrupting the special operation supposedly through his instruction that it be postponed. The President’s Office had been denying for a long time that the operation even existed, but admitted later that preparations for it had been underway. However, they objected to giving any instructions to the intelligence services. The operation that could have been a triumph for the Ukrainian security services was, in fact, a failure.

Journalists from Bellingcat and The Insider later revealed in an investigation that Yermak had indeed postponed the operation, apparently so that it would not interfere with agreements with Russia on a ceasefire in Donbas. And that decision was the reason for the operation’s failure.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine started, Wagner units have come to Ukraine to fight again. At the moment, they can be seen most often in Donetsk Oblast near Bakhmut, whereas before it was Luhansk and Kharkiv oblasts.

The militants make no secret of their brutality - they actually brag about it. Yevgeny Prigozhin sent a sledgehammer with fake blood stains to the European Parliament in response to his group potentially being recognised as a terrorist organisation.

Our article explains what the Wagner Group is now, who its members are and what part they play in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Meeting with a Wagnerite

I meet S., a 32-year-old member of the Wagner Group, in a room that the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War has provided for our interview.

We have 25 minutes to talk. We speak Russian, and people at the Headquarters are joking that "he hasn’t learned Ukrainian yet". Soldiers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine captured this Wagnerite near Bakhmut in November.

At first glance, the man resembles Arsen Pavlov, aka Motorola, a militant from the self-proclaimed "Donetsk People’s Republic" who was blown up by an explosive device in 2016. However, unlike Motorola, this Wagnerite does not even try to hide behind an ideological desire to fight for Russia and the self-proclaimed republic.

He is not a soldier and has never served in the army. He first met Yevgeny Prigozhin, the overseer of the Wagner Group, in a Russian penal colony where he was in the ninth year of serving a long sentence for murder. So when he was offered a chance to fight for six months and then receive an amnesty, he didn’t have to think about it for long.

"Prigozhin and his people visited us towards the end of August. They got 1,300 convicts together. At first, they were talking about a full amnesty; that is, those who go to fight will have their sentences annulled and will be able to work as security guards. They offered six-month contracts with a salary of 600,000 roubles [approximately US$8,500 - ed.] per month. I can’t remember exactly what they promised for injuries, but they said they would help the families out with loans. A lot of people agreed because of their long sentences - those who had 20 or 25 years," the captive occupier recalled.

The militant recalled that the mobile connection in the penal colony was disabled during the Wagner Group supervisors’ visit.

In early September, a group of almost 200 people was flown to Rostov Oblast, Russia, where they signed contracts and underwent a 10-day training course.

"There was a base, they took everyone there and gave them new clothes and footwear. But we had no identification marks. And also they didn’t say this was a war against Ukraine. They claimed that Ukraine didn’t exist any more and there were only mercenaries there. They said we’d be in some village at first, then the forest. They trained us to attack, enter the forest, hide and shoot," the Wagnerite recounted.

After ten days of training in Rostov Oblast, the group went to the occupied part of Luhansk Oblast, where they had shooting exercises.

"We had a former convict as our leader, too. Maybe he’d proved himself somehow, and he became the leader. High-ranking Wagnerites came from time to time, wearing balaclavas. They talked with this leader separately and passed information on to him. We had no direct contact with them. I heard the nicknames Flint, Faor, Nizina. But they were all in balaclavas, so you could easily confuse a convict with a Wagnerite," the captive said.

The Wagnerites then went to another village, and afterwards to the forest.

The total number of occupiers near the forest was 400. They went on an assault in early November.

"There was a concrete road. We were told there was a forest behind it. Our section moved out and crossed the road. When we approached the forest, they told us to spread out in a line. They said there was a gas station on the top of a hill, and that we needed to go there and capture it. We had RPGs, a machine gun and grenades; I had a rifle. We spread out in a line and started entering the forest. And that was it… Projectiles started flying at us: tanks, artillery [opened fire]. Some became Cargo 300 [a military code for the injured – ed.], some had their arms, legs or heads ripped off. Screams, noise…" S. narrated.

Everyone in the Wagnerite’s section was killed. He waited for another one and came under fire with them too.

"I was hit in the neck and back. There were pieces of shrapnel, and I got a concussion. Four of us were seriously wounded - they were left lying there in the forest. One was killed instantly; another one walked with me, but his knee was wounded and he stopped because he couldn't go on. I went to get help alone and came across some Ukrainian soldiers," the captive recalled.

That is how he ended up in captivity, where his wounds were bound and he was given medical care and interrogated.

When asked whether his attitude towards Russia’s war against Ukraine had changed after what he saw with his own eyes, he answers that it did.

"If I could have gone back, I would have gone back and carried on serving my sentence. I was lucky to survive and keep my arms and legs. The war was different from how I imagined it," the occupier says. He reiterates that Wagner's command assured them that they would be fighting mercenaries, not the Ukrainian army. "They [the Wagner command – ed.] said there would be Americans [fighting] there, that there was no Ukraine, that America, Germany and Poland were fighting instead."

"I didn’t think there would be fighting like that," the Wagnerite says.

"Have they [the Russian authorities – ed.] shown what happened in Mariupol and Bucha on TV?" I ask him.

"No. They used to show destroyed tanks, Lavrov would be saying that we had captured this or that…", the militant says, and again, he thinks back to the Wagnerites who were killed and mutilated. "It wasn’t about money or getting released any more. Not when somebody’s head is torn off and his arms and legs are hanging somewhere on a branch."

"There’s a real war going on. The Russian army is shooting at houses and civilians. To me that’s not normal. They have no business being there."

The Wagnerite says that he has family in Russia, so he hopes to be exchanged as a prisoner of war.

"Of course I’d like to go back home. Although I don’t know whether something better or worse awaits me there," the man says, showing me some shrapnel that Ukrainian medics removed from his neck, thus saving his life. He carries it in his pocket.

The Wagnerite also talked about the leadership’s orders that they should never surrender: "They said we should blow ourselves up. But what if there was nothing to do it with?"

The story of the murder of a former Wagner prisoner of war with a sledgehammer blow to the head shows what can happen to those who surrender.

Commenting on the video of the murder, Yevgeny Prigozhin initially said, "A dog deserves a dog’s death". Later he denied that his mercenaries were involved and claimed the US intelligence services were behind the murder.

Andrei Medvedev, the executed Wagnerite’s former commander, told The Insider that he knows of ten such "executions". Medvedev said the killings were carried out by a special unit within Wagner’s security service.

Important Stories [an online publication that specialises in investigative journalism – ed.], has been keeping count of recruits to the Wagner Group, and says that as of 19 September, at least 5,786 convicts may have been sent to fight in Ukraine.

According to Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence, the number of Wagnerites currently involved in the war is 25,000. The number was about 5,000 before they started recruiting convicts.

From the shadows to a "Russian brand"

Yevgeny Prigozhin is the head of the Wagner Group and the owner of a Russian company named Concord.

Prigozhin has been known as "Putin's chef" ever since investigations by Bellingcat and The Insider revealed that in addition to working on military matters in cooperation with the Russian secret services, Concord was in charge of organising catering for the Russian leadership.

The Wagner Group was formed back in 2014 by Russian secret services after the collapse of the "corpsmen" – mercenaries of the Slavonic Corps, a private military structure that operated in Syria in 2013.

Recruitment to the Slavonic Corps was carried out by the Moran Security Group, a Russian security company owned by Vyacheslav Kalashnikov, a former officer of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB). The operation failed. The FSB detained some of the recruits, and the court sentenced them to short terms of imprisonment.

The withdrawal of the mercenaries from Syria was led by Dmitry Utkin, a former commander of the 700th Separate Special Forces detachment (military unit 75143) of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces. Utkin’s call sign is Wagner. It was Utkin, under the personal number M-0209, who later headed the newly created private military company known as the Wagner Group.

"According to the information we have, Dmitry Utkin visited the territory of Ukraine several times to coordinate the work of Wagner. Personally, he mostly stays at Wagner’s headquarters in St Petersburg," said Andrii Yusov, a representative of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence.

"Utkin is the one who currently has direct control over the Wagnerites’ operations, as Prigozhin’s role is mostly political," Yusov explained.

In December 2021, the Security Service of Ukraine served Utkin a notice of suspicion in absentia for encroachment on the territorial integrity of Ukraine. Investigators established that he had been in the temporarily occupied territory of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts between July 2014 and March 2015, by prior agreement with high-ranking officials of the Russian Armed Forces and under their control.

Utkin commanded the Wagnerites on the Debaltseve front back in 2015.

According to the investigation, he coordinated his actions with the commander of the 2nd Army Corps of the Russian Federation, which was headed by Sergei "Tambov" Kuzovlev at the time.

The Ukrainian prosecutor's office has put Kuzovlev on its list of 18 people who are suspected of committing particularly serious crimes against the foundations of the national security of Ukraine.

For the whole of the Wagner Group’s existence, its head, Yevgeny Prigozhin, denied any involvement, even suing media outlets that proved this connection.

And Vladimir Putin has only made brief comments: "We cannot and will not ban PMCs" and "If they don’t break Russian law, let them operate".

However, this year, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Prigozhin admitted his involvement in the founding of the Wagner Group and its role in the fighting in Ukraine and "Arab countries".

"I have been dodging the blows of many opponents for a long time with one main goal – so as not to expose these guys, who are the basis of Russian patriotism," Prigozhin said, explaining why he had distanced himself from Wagner for so long.

Russia is currently trying to create a military brand using Wagner, rather like an "orchestra". The mercenaries are referred to as "musicians" and the battles "concerts". Some of the fighters, in addition to a badge with an image of a skull and the letter "W", have another one with musical notes on it.

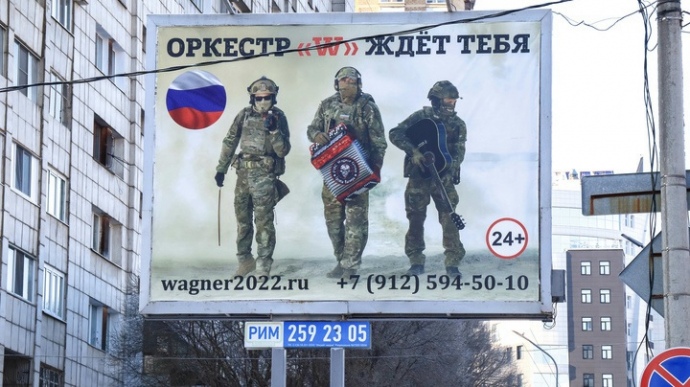

An active advertising campaign for the PMC is underway. Advertisements including the terms and conditions of service are posted on social media, advertising sites and billboards.

To join the group, you must be aged between 24 and 50, have no convictions for rape, terrorism or extremism, and not have certain medical conditions – drug addiction, tuberculosis, HIV, cancer, diabetes, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C.

"Really show you’re Russian." A Wagner Group promotion on social media

Mercenary recruitment is coordinated by people who go by the pseudonyms Bavarets and Mikhail. Their contact details appear on all the PMC’s recruitment advertising.

Yevgeny Prigozhin's holding company, Concord, appears to be involved in the financing. Prigozhin has also been involved in setting up the huge Wagner Centre in St Petersburg, whose stated purpose is to provide free office space for inventors, designers, IT experts and startups.

The mercenaries’ salaries range from 100,000 [approximately US$1,450] to 240,000 [US$3,480] roubles per month. Special forces get more.

"The money is paid in cash through the representative offices of Wagner PMC," said Andrii Yusov, a representative of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence.

There are Wagner offices in more than 10 regions of Russia, as well as in the occupied territories of Ukraine - Crimea and Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

The main training ground for Wagnerites is Molkino in Krasnodar Krai in Russia’s south. Prisoners are mainly trained in Rostov Oblast. Recently, Russian propagandists visited Molkino for the first time and showed how training takes place there.

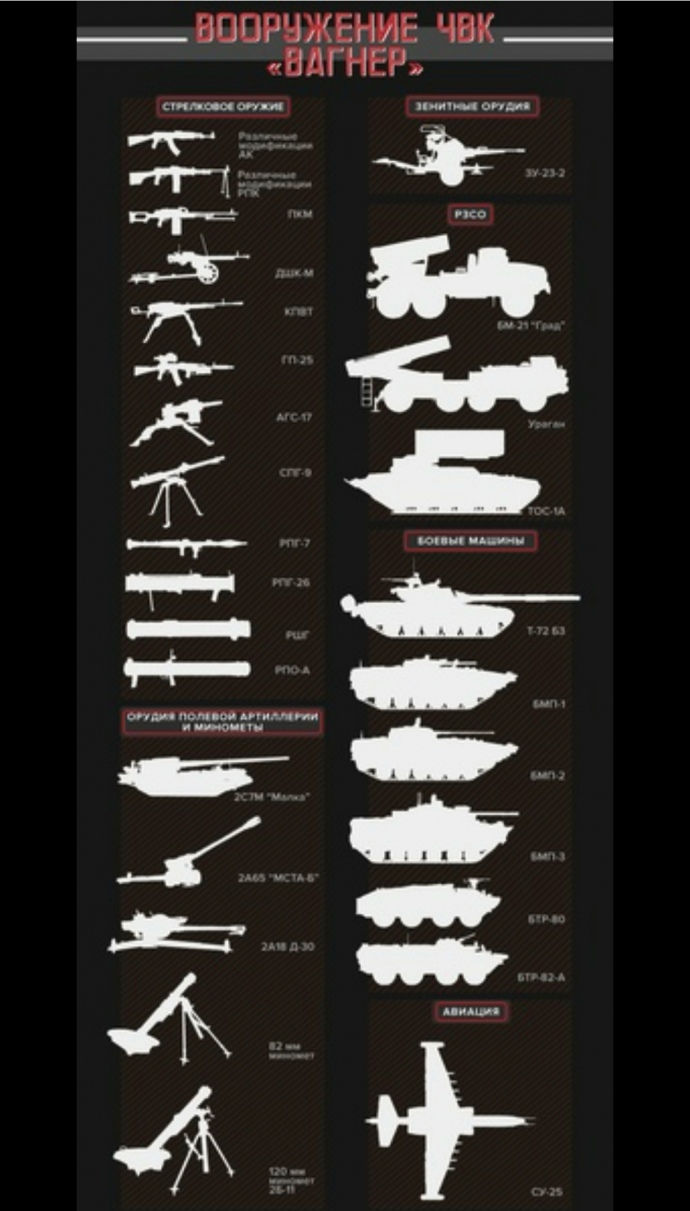

According to their own reports, Wagnerites are equipped with small arms, artillery, mortars, anti-aircraft guns, multiple-launch rocket systems, tanks and aircraft. A Wagner SU-24 aircraft was shot down on the Bakhmut front the other day. Two fighters were killed.

One of the fighters’ instructors at the moment is Andrey Bogatov, aka "Brodyaga" (Tramp), who is close to Prigozhin and until recently was the commander of the 4th reconnaissance assault company of the Wagner Group. Vladimir Putin awarded him the title "Hero of Russia" in 2016.

According to Ukrainian law enforcement officers, Sergei Pavlenko, Bogatov's personal driver and a member of the private military company, was one of the militants arrested in Belarus in 2020.

In addition to training fighters, Bogatov is also coordinating the construction of the so-called "Wagner lines" – defence points on the borders of the "LPR" and "DPR" [the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics], as well as in Belgorod Oblast, Russia. Prigozhin has not ruled out building similar lines in other regions of Russia.

Aleksandr Blinov is the Wagner Group’s chief military doctor. In 2022, he was wounded in occupied Popasna, Luhansk Oblast. In the hospital, he gave an interview to the Russian propagandist Aleksandr Simonov, who worked with the group in the occupied territories.

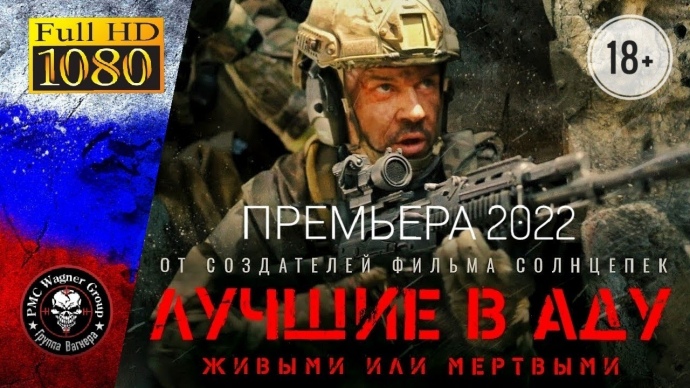

Films are made about Wagner in order to create a positive image. One documentary, "Wagner PMC: A Contract with the Motherland", is the work of a Russian propagandist who accompanied mercenaries on combat missions and interviewed them.

The second "Best in Hell" film is a feature film directed by Yevgeny Prigozhin and the now dead Wagnerite Aleksey Nagin. In the latest film, the mercenaries’ slogans are read out: "We have a contract. A contract with the company. A contract with our family. With our conscience", and "We know we’re going to hell. But we’ll be the best in hell."

Some of the rules of the so-called "Wagner code" are also spreading.

Prigozhin explained some of these rules when he was recruiting inmates in a penal colony:

"The first sin is desertion. No one gives in, no one retreats, no one surrenders. During your training you will be told about two grenades that you must have with you.

The second sin is alcohol and drugs.

The third is looting. Including sexual contact with women, flora, fauna, men, anyone…"

In addition, a conflict has been going on for a month between Yevgeny Prigozhin and St Petersburg Governor Aleksandr Beglov regarding the burial of Wagnerite Dmitry Menshikov on the Avenue of Glory.

Beglov claimed the Wagnerites were not "participants in the special military operation" and refused permission. Prigozhin said that by doing so, Beglov was "helping the Armed Forces of Ukraine". He later asked the State Duma to grant Wagner fighters the appropriate military status in order to resolve the issue of the burial.

Old acquaintances

Who is fighting for the Wagnerites in Ukraine?

A small-scale investigation by Ukrainska Pravda has revealed that some of the mercenaries were detained in Minsk in 2020.

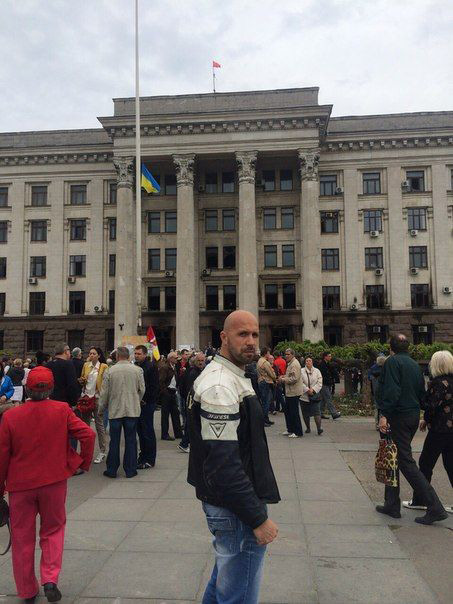

The man in this photograph is 41-year-old Maksim Koshman, nicknamed "Korshun" (Kite).

He has been a freelance fighter with the Wagner Group since 2014 and is one of 33 mercenaries who were detained in Belarus in 2020 and handed over to Russia.

His body is tattooed with the motto "Only God can judge me" in English.

This clearly illustrates the position of the majority of Wagnerites, who are used to living by the slogans "Our business is death, and business is going well" and "Nothing personal – we were paid."

Criminal proceedings have been filed against Koshman in Ukraine for his participation in an illegal armed group during a sham referendum in Sloviansk in 2014.

After the Ukrainian military established control over the city, Koshman fled to occupied Horlivka and continued to fight against Ukraine. He later obtained a Russian passport.

A review of his social media shows that he still lives in the self-proclaimed "Donetsk People’s Republic" and has been decorated by the terrorists.

Immediately after the Wagnerites were extradited [from Belarus] to the Russian Federation in 2020, Koshman and another mercenary gave an interview to Russian propagandists in which they insisted that they just wanted to earn some money as site security guards. They claimed they had been framed by the Ukrainian special services in a sting to capture Wagnerites.

"It turns out that we sent the job application forms straight to the Ukrainian special services," the Wagnerites said in the interview.

Since the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Koshman has actively supported the invaders’ actions. "Yes, I know about ‘Z’. No, I am not on the territory of the Luhansk or Donetsk People’s Republics. Yes, we are carrying out combat missions," the Wagnerite posted in March.

Koshman fought in Kharkiv Oblast, where he was wounded.

On his social media, Koshman actively demonstrates a disregard for everything Ukrainian, posting photos of himself wiping his feet on the Ukrainian flag and destroying monuments to ATO soldiers. [The ATO or Anti-Terrorist Operation zone is a term used from 2014 to 2018 by the media, the government of Ukraine and the OSCE to identify Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts under the control of Russian military forces and pro-Russian separatists - ed.]

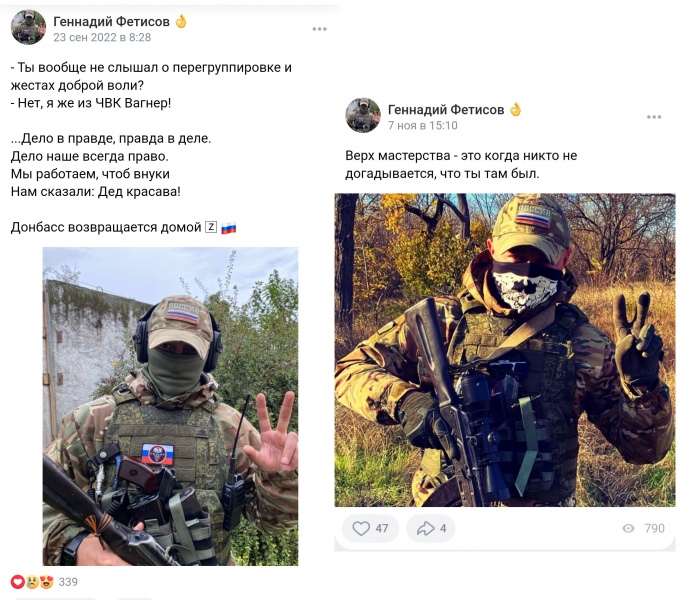

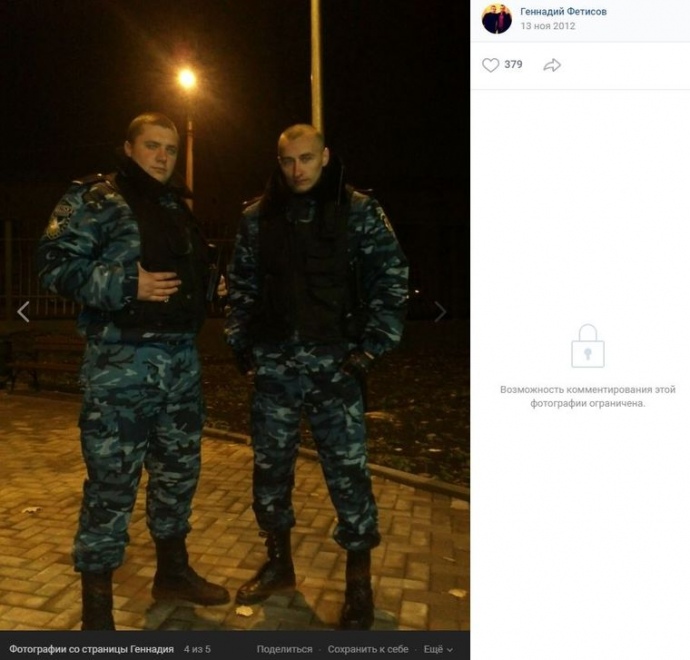

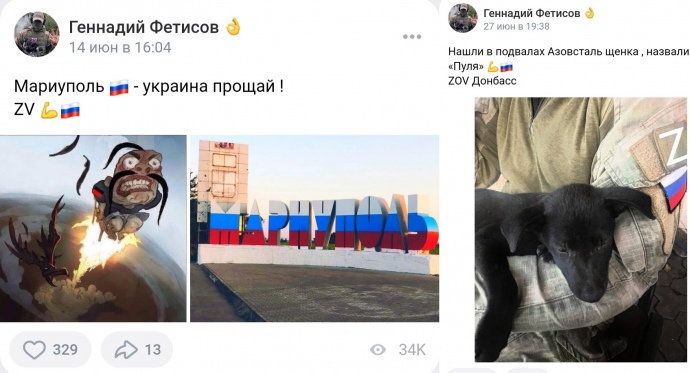

But while Koshman, despite the publicity on his social media, tries not to show off his connection with the Wagner Group (an important rule for mercenaries), Gennady Fetіsov doesn't hide it. Fetisov was also among those detained in Belarus in 2020.

Fetisov previously served in the Berkut, the infamous Ukrainian riot police unit disbanded in 2014. Now he lives in the self-proclaimed "Donetsk People’s Republic" and is fighting against Ukraine.

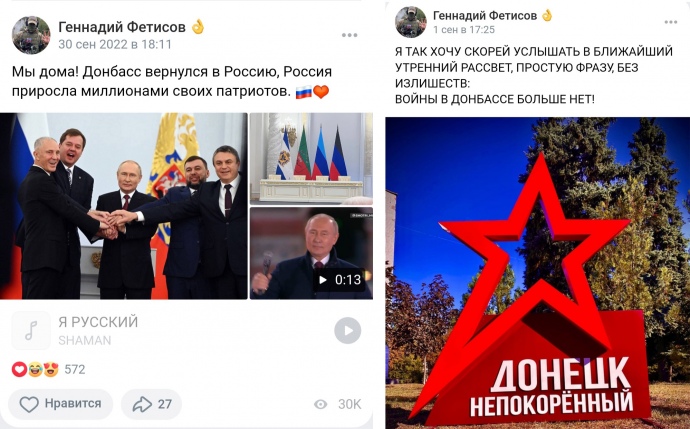

Fetisov was a keen supporter of the start of the "special military operation" and the sham referendum on social media.

"We're home! Donbas has returned to Russia! Russia has grown millions of its patriots," he posted on social media after the results of the sham vote were announced.

On the morning of 24 February, Fetisov posted a video message from Vladimir Putin on social media with the caption "Zakhodim!" [Russian for 'We are coming in', but the first Cyrillic letter was replaced with the Latin letter 'Z', the Kremlin's propaganda symbol of war.]

He also posted a photo from Mariupol captioned "Mariupol. Goodbye, Ukraine!"

Vladimir Selikhov, another of the former Wagner mercenaries detained in Minsk, also supports Russia's war against Ukraine.

Selikhov posts hardly any photos from the war. Only a few are of him in uniform and feature the Russian flag. In the others he is wearing plain clothes, but in the comments, he explains that the photos are old.

His friends comment, "I’ve received a call-up notice", and he replies, "You’ll be coming to join us with your call-up notice." This may also indicate that he is currently at war.

Andrei Chernyshov, another Wagnerite, took part in the seizure of Luhansk airport in the summer of 2014. Four years later, he was put on the SSU list as a mercenary who was taken to Syria on the Varyag missile cruiser and fought there. He returned to fight against Ukraine in 2022 and was killed in the summer.

Anton Vakhturov, a native of Komi, was also killed in the war against Ukraine. This is evidenced by videos shared on social media and in local news.

According to former employees of the Ukrainian special services, Vakhturov took part in the execution of a civilian in Syria.

Wagnerites tortured an unarmed man, cut off his head, smashed it in with a sledgehammer and burned the body. The whole thing was filmed by the fighters on video.

Vakhturov also posted photos of himself with a militant nicknamed Givi on social media, but he later deleted the page.

Who else?

According to Ukrainian soldiers who have faced the Wagner Group in battle, its members are divided into "skilled fighters" and "cannon fodder".

Most of the "skilled mercenaries" have been fighting since 2014. They are the main force of the Group.

41-year-old Aleksey Nagin, aka "Terek", is known as a Wagner professional. He was the commander of one of the Group’s assault detachments and took part in the capture of Popasna in Luhansk Oblast. He previously served in the Special Forces of the FSB and worked for Wagner in Syria and Libya.

With Yevgeny Prigozhin, Nagin co-authored the films "Solntsepyok" and "The Best in Hell". He was killed fighting in Ukraine in September.

This photo shows Maksim Koshman, whom we have already mentioned, and Vyacheslav Korneyev, aka "Leshy". He served in the Special Forces of the Russian Air Force.

"Leshy" then became a mercenary in the Slavonic Corps, the forerunner of the Wagner private military company. He took part in the Chechen war and fought in Dagestan, Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Bosnia. As a member of the Special Forces Battalion, "Leshy" fought in Donbas and Syria, where he was wounded.

In the spring of 2014, he was seen in Odesa near the House of Trade Unions. This is evidenced by a photo that he posted.

Law enforcement officers suspect that he came to Ukraine to recruit Ukrainian soldiers.

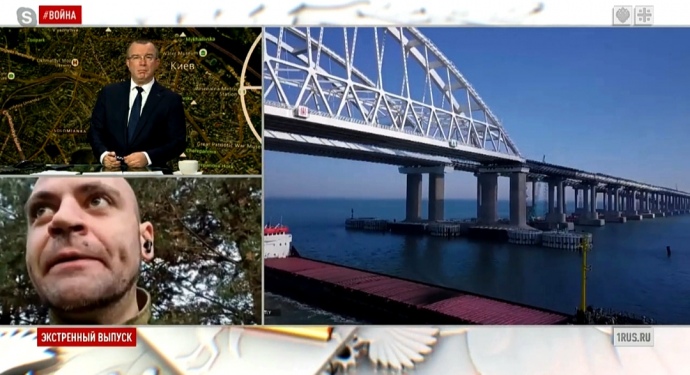

Another Wagnerite and former Odesa resident, Dmitry Dzhinikashvili, is also currently fighting against Ukraine in Donetsk Oblast.

Dzhinikashvili has been a frequent commentator on Russian television channels. He commented on the blowing up of the Crimean Bridge, calling the event a "slap in the face", and added that the Ukrainians "demonstrated a high level of professionalism".

Until 2013, in Odesa, Dzhinikashvili was linked to the pro-Russian organisation "221. Not One Step Back." In 2013 he went to Russia.

Some Wagnerites are former FSB employees.

For example, Vasily Vasiliev came to fight against Ukraine. He is a former employee of the Russian secret services who became "enlightened" in Syria. He was killed in Ukraine in autumn 2022. A friend of his who was raising funds for his funeral wrote about this on Russian social media.

Wagnerite Fedir Kryachkov was captured by Ukraine in the summer. Further to a petition by the prosecutor's office, a court in Dnipro sentenced him to 6½ years in prison for the events of 2015.

Then, in occupied Luhansk, Kryachkov joined the "Government Security Service" under the so-called "Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Luhansk People’s Republic" and provided personal protection for Igor Plotnitsky, the pseudo-republic’s former "leader".

After that, he went to Russia and joined the Wagner Group. He worked in Syria. During the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, he fought on the Izium front, where he was captured.

According to the Luhansk Oblast Prosecutor's Office, which supported the prosecution in court, Kryachkov learned about the opportunity to fight in Ukraine from a former acquaintance who goes by the pseudonym "Vortex", who is also fighting in Ukraine.

"He was promised, in his own words, $2,000 plus 50% of each combat encounter," said the Prosecutor General's Office.

Kryachkov is currently in a penal colony in Ukraine, awaiting exchange.

Aleksandr Martyshkin, a 47-year-old Wagnerite, went through the Chechen war and Syria. He was killed fighting against Ukraine. Yevgeny Prigozhin came personally to pay his last respects.

The death of Wagnerite Igor Stepanov in the war against Ukraine was reported in the Russian media. Stepanov served in the air force of the Northern Fleet, in the air assault company, retiring in 2011. During the war in Ukraine, he volunteered in Russia, later joining Wagner as the commander of a division in the assault squad. He went to Bakhmut, where he was killed in September.

33-year-old Andrei Trofimov is another Wagnerite who has been killed. He was a member of a patriotic military movement in Rybinsk, Russia, and subsequently joined the Wagner Group. He was killed fighting near Bakhmut.

35-year-old Mikhail Shalupov was obviously an experienced Wagnerite. His death as a member of the PMC was reported on social media.

His status on his social media page is "Polite people" [a Russian euphemism for the "little green men", Russian troops who first appeared in Crimea in 2014], and his wife still posts about how much she misses him and congratulates him on his professional holiday, the Day of the Military Intelligence of the Russian Federation.

Pavel Prigozhin, the son of Yevgeny Prigozhin himself, is a fighter with the Wagner Group. In an interview he gave to a Russian journalist about the situation on the Bakhmut front, he mentioned that he works in the intelligence group.

"Our work is to identify the enemy and provide coordinates, then other specialists work on them," Prigozhin Jr. said.

"The situation is tense. The enemy is increasing all its forces and resources. Work is ongoing," Pavel explained, adding, "The Ukrainians are well prepared."

The jailers

Since summer 2022, Yevgeny Prigozhin has stepped up the recruitment of prisoners to the Wagner Group.

As it turned out, most of the new Wagner mercenaries are convicted murderers - because it is usually those who received the longest prison terms who agree to sign contracts with them.

For example, Viktor Belkin, a member of the "Orenburg contract killers" gang which is infamous in Russia, became a Wagnerite. According to his father, he had expressed a desire to take part in the war against Ukraine and applied to join the Wagner Group. Belkin's gang is suspected of eight contract killings. One of their victims was a seven-year-old boy. Belkin was sentenced to 21 years’ imprisonment.

23-year-old Denis Zagornov was sentenced to six months in prison in May 2022 for multiple thefts. He was recruited in the penal colony to fight with the Wagner Group. He was killed and posthumously awarded the Order for Courage.

56-year-old Wagnerite Alexander Smirnov died in September in Ukraine. He was also recruited in prison and promised that five years of his unserved sentence would be "written off".

33-year-old Wagnerite Lev Zhemzhur was also killed fighting against Ukraine near Bakhmut. This information was posted on Russian social media and confirmed by his wife.

In photos posted by him on social media, a "thief's star" tattoo is visible on his body, indicating his multiple convictions. He is likely to have been recruited to the Wagner Group in prison, since he has no photos related to the war or intelligence.

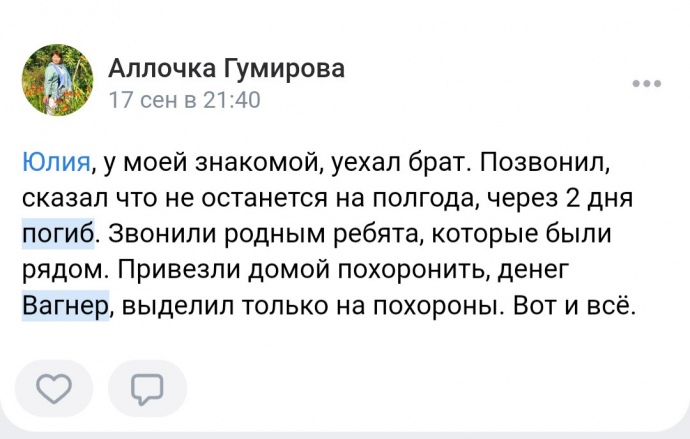

Since communications in the prisons are jammed when Wagner representatives are visiting, relatives of the recruits most often learn that they were fighting against Ukraine after their death or capture. Only a few of them manage to get information from the prison authorities.

There is even a group on social media where prisoners’ relatives can search for them. They write that usually when Prigozhin arrives at the prisons, the connection disappears. This is also confirmed by former prisoners in the comments.

"When the Wagner Group arrives, the connection is turned off until they [the recruited prisoners - ed.] have been taken away. It's about a week. I’ve just been released - I know," one posted on social media.

Groups for Wagnerites’ relatives urge people not to post anything about their family members on social media, as they claim the Ukrainians might make use of this.

How the Wagnerites are fighting in Ukraine

Ukrainian soldiers who have faced them on the battlefield, now mainly in Donetsk Oblast, say that there are strong opponents among the Wagnerites.

"Of course they have units that know how to fight. They send the zeks [prisoners] to do reconnaissance in battle, because they don’t care about losing them," says Vladyslav, a member of the Bakhmut Territorial Defence Forces. "They attack positions very defiantly. Apparently they think they’re immortal.

There was a case where a group climbed into our trenches in our military uniform. Their intelligence had probably failed. The battle began. From the second flank, our fighter immediately cut off the approach of another part of the enemy group with grenade launcher shots. Our people heard them say, ‘What the hell… the ukrops [a Russian ethnic slur for Ukrainians] are here?’ The battle was somewhere up to a minute long before they began to retreat."

Anton Petrivskyi, a high-ranking soldier in Ukraine’s 80th Separate Air Assault Brigade who has also encountered Wagnerites in battles in Donetsk Oblast, told us more about them.

"In their tactics and training, they stand out from other units of the enemy army. They are more disciplined and creative. They have their internal tradition of waging war, formed in various local conflicts. They have better material support," he says.

"But they’re still cowards, immoral elements. When they meet a worthy opponent, all their grandstanding bursts like a soap bubble and they die one after the other."

Anton says the Wagnerites have their own so-called "Honour Code".

"Not surrendering is important to them. They try not to underestimate the enemy and are responsible for planning their operations. The Imperial component and the dominance of the Russian nationality are very strongly present at the heart of their ideology."

Another Ukrainian soldier, nicknamed "Zamok", who also encountered Wagnerites in the war, said he felt they had a significant level of training.

"A lot of money is invested in them. They have good equipment, weapons, aerial reconnaissance and communications," Zamok said. "They would change into our camouflage and come to our positions. They have people who speak Ukrainian quite well. And this story didn't always end well for us. Sometimes our guys were abducted from their positions."

According to the soldier, the Wagnerites are suffering significant losses and are therefore forced to use prisoners as reinforcements.

"Now they are attacking in small groups to detect firing positions. And it’s usually the prisoners who are sent to do this. If they do break through somewhere, then professional reinforcement comes."

What is the main role of the Wagner Group in the war against Ukraine? According to Ukrainian defenders, the private military companies’ mission is to create a so-called "elite military benchmark" in Russia.

"To be a role model for other units. The Moscow Command has certain hopes for them, and they work in the most difficult areas," says Anton.

Zamok adds that there is now an internal conflict in Russia between PMCs and the regular army.

"PMCs in Russia, such as Wagner and the Kadyrovites, are competing with the regular army. They are all well aware that ‘the tsar is not eternal’. And what will happen to Prigozhin and Kadyrov after the war? Every demigod wants to be a God," he says.

When asked why he thinks Wagner is being turned from a super-secret structure into a brand, Zamok observes, "It used to be a business for them, but now the conflict is open and they have been exposed. So the best way out for them now is to start promoting themselves."

Andrii Yusov, a representative of Defence Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, says the Wagnerites do not play a decisive role in the war, although some important areas at the front are shifted to them. "There is a deliberate PR campaign going on for the PMCs, the role of which is mostly political. This is about Yevgeny Prigozhin's political future," Yusov says.

However, this is more likely to speed up the process of Wagner being designated a terrorist organisation, which has already been proposed in the US Congress.

This means that punishment for the mercenaries for their crimes against humanity in Ukraine will not be long in coming.

Victoria Roshchyna, for Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Myroslava Zavadska, Artem Yakymyshyn, Elina Beketova, Yuliia Kravchenko, Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Liudmyla Lesiv

Editing: Teresa Pearce