"They say on TV that we are winning. If only they knew at what price." One day at a first-aid post in Bakhmut

With gratitude to all units

Who stood and still stand in the heavy defence of Bakhmut

With reverence to every serviceman who

died, holding back the Russian attack on this city.

"The situation remains the same."

"The enemy is concentrating their efforts on conducting offensive actions."

"They have targeted the settlements of… from tanks, mortars, tubed and rocket artillery."

These are the customary language constructs from one of the General Staff reports at the beginning of December.

Behind these words are life and death, loss and hope, the smell of the first winter frosts, blood, sweat and cigarettes.

On this day, when the Russian army was intensively attacking Bakhmut from three directions, Ukrainska Pravda had the opportunity to work in one of the first-aid posts on this front.

It was only one of 300 days of this big war.

***

"Heavily wounded"

At 11 o'clock in the morning, behind the closed doors of the first-aid point in Bakhmut, these words sound almost casual, unemotional, without exclamation marks.

The doors open.

A few servicemen, holding a stretcher made from a dense, dark green fabric, carry in their injured brother-in-arms.

They pass the first room by the entry, where medical staff treat soldiers with light injuries, and rush hurriedly to the next one, with two operating tables.

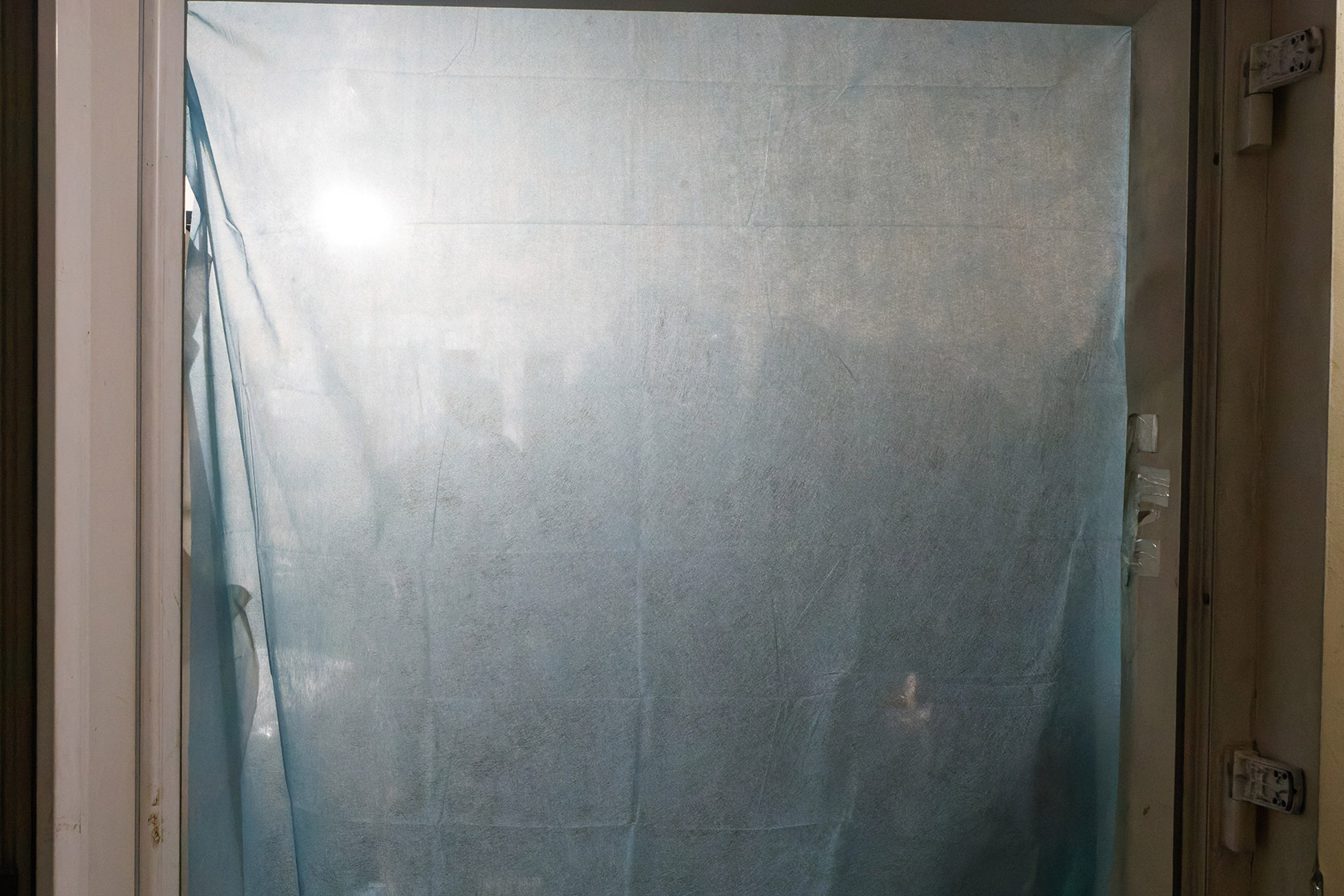

The silhouettes of the doctors can be seen through a thin light-blue curtain that divides this room from the corridor.

The doctors work silently and quickly, they can be barely heard from the corridor.

They undress the newly arrived patient from his uniform and begin to stabilise his condition. All their actions are almost automatic. Their main objective is to replace the tourniquets applied when on the battlefield, bandage the wounds, and provide with pain relief.

X-rays and extraction of debris that caused this bleeding is the next stage of care provided in military hospitals.

The "heavy wounded" one, as Ukrainska Pravda soon finds out, is a soldier from the 57th Brigade known as Tsar. His head is severely injured and he has a heavy concussion.

His counterpart Hlib, by the looks of him 30 years old, sits on the bench in the corridor and every few seconds takes a deep breath. He is trying to say something to the doctors who surround him, but none of the words are tangible.

"Relax. You can’t walk around in the hospital with weapons, and you have a rifle and four magazines." The doctors try to make him put down his weapon.

The corridor is filled with the smell of hot soup, which some of the personnel of the first-aid point are eating nearby.

In a few seconds, the medical staff notice a small wound on Hlib's neck. After examination, they state that everything will be fine - the wound is small and not even bleeding. But it is not important for him to hear this right now.

"I need to get in touch, I need to get in touch," he finally explains.

Picking up either his phone or a walkie-talkie, Hlib quickly and coherently reports to the commander:

"It’s me, Tsar. No cargo 300s or 200s [the codes for transporting injured and dead soldiers respectively - ed.]. Took everyone out, we are in the hospital, then on to the city of N."

Only after these words does he give his rifle to the medical personnel, as well as his plate carrier, on which four magazines are fixed, and allow his neck wound to be sealed. Fortunately, it is still not bleeding.

A few minutes later, when the first shock has passed, Hlib goes out on the porch of the first-aid point, takes the first puff on a cigarette and tells his comrades how he almost bought it on the battlefield today.

One of his sentences quite fully describes what Ukrainska Pravda’s journalists have regularly heard in the war zone during the full-scale invasion:

"They say on TV that we are winning. If only they knew at what price."

Hlib "pays" for the victory not only with today's wounds to the neck. A few months ago, near Lysychansk, he lost an eye.

***

There are a lot of soldiers from the 57th Brigade here - the guys hold one of the most difficult sections of the Bakhmut front.

"We are mowing them down quite successfully - both at night and during the day, and still they keep coming like cockroaches." A soldier from the 57th brigade named Serhiy is surprised.

He has been spending a third hour in the corridor of the local first-aid point, waiting to be evacuated to the hospital. In the morning, Serhiy's trench was abundantly covered by fire from Russian AGS

"We have been sitting in that trench for five days, our dry rations have frozen." He tells how the arrival of winter affected the work of the infantry in Donetsk Oblast.

"You could say that we were eating ice," adds his comrade.

Our conversation is interrupted by a short girl in civilian clothes, probably a volunteer. She distributes clean clothes to the soldiers for further evacuation to the hospital.

"These are sporty, they stretch." She points to a pair of grey cotton pants.

"Do you still have white socks?" one of the servicemen asks.

"It's a bit too early for that," joke his brothers-in-arms.

Only the heavily wounded don't joke here - those behind the blue curtain. Everyone else - no matter how much debris is inside their body - laughs as long as they can.

A soldier from the same 57th Brigade named Valery is sitting a little apart in the corridor. Unlike Tsar, Hlib and Serhii, it was not the Russian AGS that got him, but a Russian mine.

Valeriy and his comrades, running between the trenches, had to deliver radios. When the Russians spotted them, a battle ensued. One mine fell right next to Valeriy, but he managed to fall to the ground and survive. Another grenade flew into the trench - his comrade was wounded in the leg, there was no way to evacuate.

"In the evening, the Russians knocked us out of that point, but in the morning we went to recapture that position. The position was retaken, but the guy with the leg has his head shot... I'm sorry." Valery abruptly ends the conversation and turns away to the wall.

And then he adds: "We never delivered those radios."

The only one who has never sat down on the corridor bench this morning is a soldier from the 57th Brigade known as Dionysus. To put it bluntly, he simply cannot do it - a fragment from a Russian projectile is stuck in one of his buttocks.

Dionysus, like everyone who is not behind the blue curtain, laughs.

***

"We f**ked up the bastards, sh*t. But oh well, we're alive and they're dead, the c**ts. No bother, we will heal now and come back," says Hlib to his comrades in the courtyard.

Soldiers smoke and drink Coca-Cola from small tin cans. A man with an injured lower lip is being aided by his comrades - carefully, holding the can above his mouth, they help him drink.

"Me, no, I will not return quickly." Dionysus continues Hlib’s train of thought.

"Well, you have a serious wound, a deep one. I looked at him... I will never forget the sight of it," Hlib laughs.

"I'm standing there bent over, and Hlib is f**king tamponing the wound!" Dionysus explains the reason for Hlib’s laughter.

"And I haven't seen a woman for several months," says Hlib.

"Barely held yourself back, right? A real comrade!"

Now everyone bursts out laughing.

***

Tsar was evacuated to a hospital at 11:30 in a separate ambulance car with oxygen connected to him.

***

"Who has a form 100?"

In the language of medics, this question actually means: those who have already received first aid and have a relevant record in their cards are free to go to a hospital in the city of N.

A dark green non-armoured medical evacuation vehicle (medevaс) usually takes twelve people sitting and four lying down, but this time everyone was sitting. Dionysus, the thirteenth person, jumped in the vehicle which had already started.

"I’ll stand," he told the medics.

The car slowly left the first aid post at 12:14. There were no seriously injured people inside, so there were no flashing lights.

A combat medic called Oleksandr who had been serving his fourth month at the time (and worked as a miner in Pavlohrad prior to this) and an experienced driver Yevhen who has been in the Armed Forces of Ukraine since 2017 are in the front seats.

They do one trip every day in quiet times and up to four or five during an offensive. They rarely transport those who have been killed.

Yevhen has recently made four evacuations in one day during the repelling of an attack on the settlement of M and took 55 people to hospital.

These are enormous numbers, compared to losses of the Ukrainian army before 24 February.

"I was instructed to go with the Aidar Battalion in 2018. And I took 30 soldiers and 4 Cargo 200s to an evacuation point in half a year. Now, I can take 50 injured people in a day, you see?

There were Minsk agreements before the full-scale invasion… 120 calibre, 152 self-propelled artillery units were used on very rare occasions. It was mostly small arms, there were fewer losses," Yevhen recounted.

But he is not from those who miss the times of the Minsk agreements. Even despite the fact that his native village Stanytsia Luhanska was not occupied before 24 February.

We got to our destination point in a couple of hours. It was a military hospital in the city of N. Stretchers placed beside the main entrance in several rows are mostly clean as opposed to Bakhmut.

Twelve servicemen were heading to the surgical department, and one with lighter injuries was going to the therapy department. Before the parting of their ways, they all lit cigarettes.

The dark green medevac took five soldiers. Ten small fragments were remaining in the body of one of them.

As the chief doctor of the first-aid post in Bakhmut would explain later, this meant that it was life threatening to remove those fragments. But they would not move inside the body in any way.

These are the traces of war that stay with you forever, to put it bluntly.

A tanker greeted the green medevac with a raised hand a few kilometres from Bakhmut. He had a Ukrainian flag behind his back and no strikes visible on the horizon yet.

The evening sun shed a lot of light over Druzhba park and the MiG-17 fighter jet monument at the entrance to Bakhmut. This monument is dedicated to Soviet cadets who took part in World War II. If you do not turn your head right - to the plant, destroyed in spring - it could seem like it is a typical December night falling on a typical Ukrainian city.

***

A queue of injured soldiers appeared near the first-aid post again after 15:00. There was another heavily wounded person behind the blue curtain.

The local chief doctor, a surgeon called Serhii from the 93rd Separate Mechanised Brigade Kholodnyi Yar, was called to the yard where a white volunteer car stopped.

"We brought medicines, take what you need," a short girl in a bulletproof vest told Serhii.

"You see, it might appear that we do not have anyone to go through those medicines now…," Serhii explained the workload at the first-aid post.

But still, he instructed someone to perform this task.

"Who is to be evacuated? Who has Form 100? Who has a face injury here?" medics were shouting in the corridor.

Yevhen, Oleksandr and their dark green medevac were not in the yard any more. Another crew would take care of this evacuation to the city.

The heavily wounded soldier was taken from behind the blue curtain in a black plastic bag.

"They didn’t manage to resuscitate him," Said Ismagilov, a former leader of Ukrainian Muslims and a paramedic now, said quietly while standing in the corridor of the stabilisation point.

"Injury incompatible with life," the laconic surgeon Serhii would say later.

The first-aid post’s doors opened with the words "There is a Cargo 200" at 15:52. Only the medics reacted. They always know what to do.

Several servicemen from the 57th Brigade were sitting in the corridor.

Misha, a soldier, received an injury in his arm and jaw because the Russians attacked his position with tanks. According to him, no one survived at one of the sites.

His namesake Mykhailo was injured a few days ago but managed to evacuate only then: "We heard voices of those bastards on the morning of 30 November, and that was it, the battle started. It lasted until 3 or 3:30 pm. My fingers still hurt. We retreated slightly then, we had injured soldiers and no connection. All the drinking water froze, you see?"

At 16:45, the doors opened once again, but this time with the words "Is there anyone to help? There is a man lying injured here."

"Guys, anyone, help," a person on duty from the 57th Brigade repeated the request.

The heavy doors of the green vehicle slammed outside, and another patient was brought into the first-aid post on the white stretcher.

The first-aid post got one more blood-stained stretcher.

***

At 17:00, the part of Bakhmut near the front line descended into complete darkness.

Nothing was visible on the streets - no outlines of buildings, no craters on the roads, no ragged power transmission lines.

A few months ago, you could say that this was a 10 out of 10 blackout level. But it is simple at the moment: the city does not have any electricity at all. There is a war in the city.

Only sounds fill in the entire city space: the nearest ones are from numerous vehicles carrying the injured, the distant ones are periodic explosions.

A scent of the first December frost also fills the air. It erodes all the rest - those of blood, sweat, cigarettes and petrol.

Sometimes it is probably for the best that the war has a smell of frost.

A civilian passenger car started across from the first-aid post. Dipped headlights were turned on, pouring their light onto the yard of the first-aid post and three black plastic bags that were not visible in the darkness.

Said Ismagilov was not there at the moment, but his words still hung in the air: "They didn’t manage to resuscitate him."

As did Hlib’s words: "They say on TV that we are winning. If only they knew at what price."

Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Theodore Holmes, Myroslava Zavadska

Editing: Susan McDonald