Timothy Snyder: Russia calls itself a democracy, but it's obviously not

"Fascists calling other people ‘fascists’ is fascism taken to its illogical extreme as a cult of unreason. It is a final point where hate speech inverts reality and propaganda is pure insistence. It is the apogee of will over thought.

Calling others fascists while being a fascist is the essential Putinist practice. Jason Stanley, an American philosopher, calls it ‘undermining propaganda’. I have called it ‘schizofascism’. The Ukrainians have the most elegant formulation. They call it ‘ruscism’," American historian Timothy Snyder wrote in a recent column in The New York Times.

Not surprisingly, the publication has caused a wave of indignation in Russia.

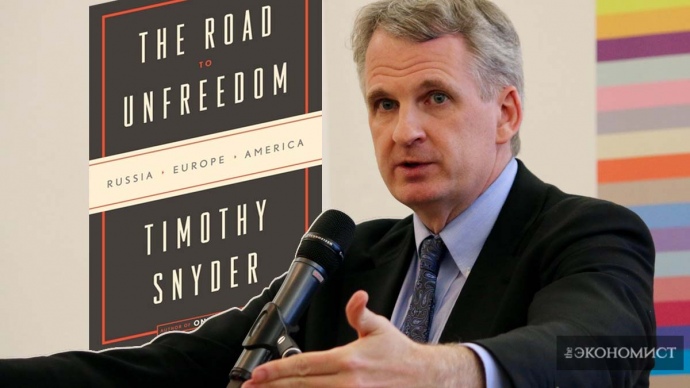

Snyder has been researching totalitarianism and nationalism in Eastern Europe for several decades. He is a professor of history at Yale University, as well as the author of several well-known books that reveal the darkest pages of the history of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia's colonial policy.

Since the earliest days of the full-scale invasion, Snyder has been explaining the phenomenon of Russian colonialism to a Western audience. In addition to his brilliant knowledge of history, you can also sense his incredible empathy for the Ukrainian resistance in his writing.

Snyder visited Kyiv for a few days in early September to attend the Yalta European Strategy (YES) international conference, and he agreed to talk with Ukrainska Pravda.

In this interview, the renowned historian shares his view of China's role in the war against Ukraine, reflects on propaganda, and explains why the Ukrainian resistance reminds him of literature.

I just had a chance yesterday to read your recent article in Foreign Affairs. One of the things that I wanted to start with is that in this article you start with the phrase that "this war is about establishing principles for the twenty-first century", and I wanted to ask what you think these principles can or should be and how they are different from the principles of the twentieth century.

So what I am thinking about is how the last thirty years have been a time without principles where the people who want the good things ‒ freedom and democracy ‒ have been persuaded that these things come automatically from history. And the problem with that is that if you don’t choose freedom, it’s not freedom. If you think it’s being brought to you, then what’s being brought to you is not freedom. You have to choose yourself.

And the other problem is that if you think the larger forces are bringing good things to you, you don’t ask yourself what the good things are, and you might start to think, whatever the larger forces are bringing me, that must be freedom, that must be democracy. Even when it isn’t. And in some way contemporary Russia is a result of this kind of way of thinking. It calls itself a democracy. And who’s to say it’s not a democracy? But obviously it’s not.

And so the very basic thing I am trying to say in the article is that if we want to have freedom and democracy, we have to start by saying that we want these things, that these are good things, that we have principles and that in some way the war against Russia is also a war against the idea that whatever happens is fine, whatever happens is good.

Ukrainian resistance is a very helpful reminder to the rest of us because the Ukrainian president and other Ukrainians have done a good job articulating the values that Ukraine is fighting for.

So when I say what are the new principles, I really just mean principles, you know, because the nature of freedom and democracy are that if you have them, that allows you to choose what all the other good things might be.

But is there a scenario where this set of principles is dark and anti-democratic?

Yes, of course. There can be a world without democracies. The United States can cease to be a democracy. If Russia wins this war, which I don’t think it will, but if it does, then that will put greater pressure on European democracies. China actively works against democracy. So, when Ukrainians say they are fighting for other people, or they are fighting for Europe, or they are fighting for the West, they are fighting for the world ‒ I think that’s true.

I think that’s true in the sense that when you have a country like Russia that not only opposes democracy around the world philosophically, not only opposes it with propaganda, but actually fights a war against democracy, you’ve moved into a very dangerous territory. And the only way to reverse that is to win the war. There’s nothing else you can really do ‒ you have to win the war.

So that’s why I think that this war is a turning point not just for Ukraine or Russia, or Europe, but that it’s a turning point for the idea of democracy in general. As Ukrainians are articulating values, on one hand, but also because if they lose, it’s not just that one country is lost, it’s that this notion that things are worth defending is also lost.

Because if Russia wins, what is it winning in the name of? The Russian war is based completely on lies. The Russian principles in this war are anti-principles. They are statements made to undermine other people’s principles. The war is based on a constant series of lies.

If they win, that means lying becomes all the more natural. This war is based on constant cynical abuse of international institutions. If they win, then that becomes normal. So it’s about affirming values, it’s about stopping Russia, but it’s also about the perception that something better is possible.

The Chinese and the Russians think that history is on their side. They think that everything that we are doing is just empty and hypocritical and naive, but, if Ukraine wins the war, it means it’s not empty or hypocritical, not naive, that we actually mean it and we are capable of realising some of the things that we believe in.

You’ve mentioned the word "values" several times. How are these principles that you’ve talked about adjacent to the notion of "Western values"?

A value is only a value if you try to realise it in the world and are ready to sacrifice something for it. If I tell you that I am from the West and so I know what Western values are and you don’t, that’s not really a description of values. A value is something you exemplify and take risks for.

And that’s actually a very powerful Eastern European intellectual tradition, which one sees for example in Vaclav Havel. But I also see it in the way Zelenskyy talks. The things that are good are things you are willing to take risks for. Otherwise, these are things not worth talking about.

So when I am talking about values, I am not saying that I have all the values and I am going to tell you what they are. What I mean is that there are many good things in the world and freedom is the ability to choose among those things. And democracy is a political system in which this freedom is possible. And that basic idea goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, all the way back to Pericles and his funeral oration.

Now I am not trying to say that’s the way the West always behaves. Or that the West has something to tell Ukraine in this sense. What’s interesting about this moment is that Ukraine is reminding the West of a certain basic part of its own tradition, which is that democracy is not something that comes from the larger world and it’s not something that comes because you say nice things about yourself. It’s something that comes because you struggle for it, because if you don’t struggle for it, pretty soon it’s not going to be a democracy.

In this evolving global situation, how do you think the roles of the UN or the EU are changing?

I think that the most important organisation for Ukraine by far is the European Union. And I think that Ukrainians were right to take risks for the European Union in 2013 and 2014.

The reason why the European Union is so important is that it is the structure that allows the post-imperial state to survive and thrive. That’s not the story that Europeans tell, but that’s the real story. Almost all members of the EU are post-imperial states, whether they were the centre of an empire or the periphery of an empire. What the EU does is that it creates a framework in which these post-imperial states can thrive ‒ people can move around freely, they can trade freely, they can have a larger conversation about history, about values.

Ukraine must become a member of the EU. That is in the interest of everyone. It’s in the interest of Ukraine because the European Union is about making better states. There are many nice things that we’ve said about Ukraine, but this state has many problems and the EU is about making states function better.

On the other side, the European Union, although it doesn’t realise this, is about the end of imperialism, is about imperial countries losing wars. If Russia wins this war, that is a direct threat to the EU because it returns imperialism to the centre of European politics.

The EU is an alternative to imperialism, the only one so far that’s been really successful. And so the EU needs Ukraine to win this war, just as Ukraine needs to join the EU.

In your book, Bloodlands, you write about the territory from the Baltics to Ukraine. However, we can see that nations coming from this territory have had very different fates. Some are better prepared to fight for freedom and some ‒ like Belarus ‒ are less ready to do so. How do you explain that?

Everything is subject to change. The Ukraine of 2022 is not the Ukraine of 1992, which is the first time I was in Ukraine. It’s a very different country. And Belarus thirty years from now might be a very different country. And it’s important to hold open that possibility.

Belarus faced, I believe, the most difficult imperial situation in the 19th century. All of Belarusian territory was under the Russian empire. It doesn’t sound like an advantage, but it is, that Ukraine was divided between two empires. When things got bad in Russia in the 1860s-1870s, the great Ukrainian thinkers could go to Galicia, to Lviv. There could always be that kind of back and forth.

The Poles were divided between three empires, which sounds like a tragedy, but that also means that one of them had to be more liberal than the others at a certain time. All of Belarus was under the Russian empire, and then within the Soviet Union, Belarus was particularly struck by the terror in the 1930s.

And then Minsk was largely destroyed and Belarus suffered more than any other country in WWII, even more than Ukraine, even more than Poland. That suffering also disproportionately affected the Belarusian educated classes. And then when Belarus was rebuilt, it was rebuilt as a kind of Soviet republic, with a huge amount of migration of Russian-speaking people from all over the Union. These are some of the reasons.

But two years ago Belarus was really close to overthrowing the Lukashenko regime; the majority of Belarusians voted for something very different. It’s not that the country is that far away from Ukrainian attitudes. Clearly Belarusians would prefer to have democracy. If there were Belarusian democracy, I am sure its foreign policy would be very different.

But they do have this regime built by a skilful politician who’s been in power for almost a quarter-century now. So those are some of the differences. There are historical constraints, but at the same time one should also be hopeful.

You mentioned China as well. What role does China play in this, and how will its role change in the future?

The first thing is that China let this war happen. This war is China’s responsibility. The Chinese government is really bad at taking responsibility. They would very much prefer to pretend that they don’t make any decisions, that the Americans are making all the decisions. But in the case of this war, America tried to stop it and couldn’t. And the Chinese didn’t try to stop it, but they could have. Instead, they gave Putin permission to fight this war in February. And then when it started, they also could have stopped it, but they just let it happen. So this is China’s war. China is in a pretty fundamental way responsible for this war.

They could have stopped it by persuading Putin to stop it?

I don’t think he’s capable of a sovereign decision for something on this scale. I think what the Chinese were supporting was the three-day war. I think they believed in a version that there will be a three-day war and it will all be over, and the West will not have time to do anything. Now there’s a longer war. Of course, China doesn’t really care about Russia and regards Russia as a kind of colony.

Now that the war is happening, they are not helping Russia because they care more about American consumers than they care about Putin. And also it’s not bad for China if Russia becomes weak because that just makes Russia easier to control. That’s the trap that Russia is now in with China ‒ the Chinese have no reason to help Russia because it will hurt China, but also in the long run they want to exploit Russian natural resources and this war makes it easier for them to do that.

In your article you also mention the Global South several times, and if we look at the dominant narrative within Global South communities, it’s explicitly anti-Ukraine and clearly deeply affected by Russian propaganda. How do you explain that?

There are people who know a lot more about Africa, Latin America and the Global South than I do. I’ll just mention a couple of basic things. One is that the Soviet Union was an anti-colonial power. Not on its own territory where it was more like a colonial power. But around the world it did support anti-colonial movements. And so from the point of view of Latin America or Africa, you are not thinking that the Soviet Union exploited Ukraine colonially. You are thinking that the Soviet Union helped us fight the French, the Belgians, the Americans.

The second thing is that from that distance, Russia is a real country and Ukraine isn’t. Sometimes it’s just as simple as that ‒ people just haven’t thought about Ukraine. I’ve had conversations with journalists and others from the Global South where I just tried to explain that Ukraine is the one that has all the food, not Russia. Now Russia also exports food, but not as much as Ukraine. Just that notion that Ukraine is somehow important was very new to people.

And I think the way forward is for Ukrainians to tell their own story, to bring people from the Global South here to Kyiv and let them see it for themselves. And for Ukrainians to tell their own history. Holodomor is a terrible Ukrainian national tragedy and has specific national elements to it, but it’s also an example of political famine in general and political famine is a general colonial phenomenon. And if Ukrainians can learn to tell the history of Holodomor that way, then maybe in the long term they’ll be able to get more sympathy and understanding.

But also we shouldn’t forget that dictators like other dictators. Wherever a dictator is, that dictator is more likely to support Putin. And it’s not just propaganda, it’s often just the regime type.

Unfortunately, Ukraine doesn’t have a lot of experience in global-scale narrative-setting. Which brings me to my next question: how do you assess the role of media and big tech in enabling the proliferation of Putin’s propaganda machine? And of course not just Putin, but also Trump, Rodrigo Duterte and so on.

In a way, that goes back to your first question about democracy and values. Democracy and freedom are fundamentally human concepts. They are not machine concepts. Machines don’t have agency, machines don’t care. One thing that we can do with machines is that we can get hold of people’s emotions. So I can use a machine to find out a lot about you and to try to manipulate you. When you are online it might feel very personal to you. But it’s not personal to the machine. It’s just you being manipulated.

For me the basic problem with social media is that it drives us towards impulses and reactions, and immediate emotional states, and away from thinking about what it is that we think is truly important. It makes us more homogenous, it divides us up into a few homogenous tribes rather than allowing us to become individuals who have the time and ability to think, "What do I really care about? What’s important to me?"

So I think it’s not a coincidence that democracy has been in trouble since 2010 when social media took over the internet. And I think people should own that. I mean different companies do different things, but the overall effect of social media has been to make us less free, less imaginative, less intelligent, less capable of talking to one another.

Again, going back to classical origins of democracy, the Greeks understood that it all depends on people’s ability to come together and have a conversation. You have different interests, I have different interests, but we all have to be able to see the world together and be able to talk to one another. And social media has made all of that harder, and therefore it’s made Trump more likely and given Putin opportunities that he wouldn’t have had otherwise. So all in all, it’s been negative. In this war, of course, Ukrainians and their friends have found ways to turn some of this around.

A lot is being said right now that in the event of Russia’s defeat, significant parts of its territory, like Chechnya and some other areas, will get separated. How likely is that? And also in general, what would constitute Russia’s defeat for you?

I think it’s better to think in terms of Ukrainian victory. Russia will not in the short term admit that it’s been defeated. And if Russia is defeated, this will have consequences, but not consequences we can control.

So I really think it’s better to think in terms of Ukrainian battlefield victory, but also in terms of what comes after ‒ reconstruction, integration with European institutions. That’s all part of victory, it’s all one story in a way.

If I were Ukrainian, I honestly wouldn’t talk about Russia’s falling apart. I don’t think Americans should talk about that. I really think that what happens in Russia is up to the Russians ‒ after they leave Ukraine.

Ukraine can do two good things for Russia ‒ win the war, and set an example of a big East Slavic state which has the rule of law and which flourishes. I don’t think there’s anything else. Empires do fall and they do fall apart, but usually the basic dynamics are unpredictable.

It could happen, but when it does happen, it shouldn’t be something that we’re paying too much attention to. What we should pay attention to is winning the war, making reforms in Ukrainian society and politics, and joining the European Union.

Liberalism and imperialism can go together. You can be a great liberal and still think that it’s your job to civilise the peripheries. And it’s not only Russians ‒ Americans and other people can think like that too.

I think it’s Ukraine’s job to say that Russia’s an empire and it’s an imperial war, that we are defending ourselves against Russian colonialism. But what the Bashkirs, the Tatars or the Chechens do ‒ I would honestly just leave that alone. It’s very unpredictable and you are responsible for your part in ending the Russian empire. It’s already enough.

After this whole thing ends, how do you think the world can make sure it won’t happen again?

The simplest thing is to make sure that Ukraine has a well-equipped army. Ukrainians have shown that as a society they are extremely capable of defending themselves. It’s the easternmost part of something that we call the West, or the European Union. And it’s going to be the country that Russia last invaded.

So making sure that Ukraine has well-equipped armed forces makes sense for anybody who wants to prevent war. And things like EU membership or NATO membership are important here. But even more important is Ukraine becoming a kind of society that they just wouldn’t try it because it’s so prosperous and successful.

They would never admit this, but their own calculation was ‒ Ukraine is doing better and better, and therefore we have to act now, because in five or ten years from now it will be too late. The national consciousness will be completely established, democracy will be completely established, so we have to act now. I think that was the Russian logic.

So after the war you just have to make that true. Keep making it a better and richer country. Rebuild the cities in a way that makes sense. Make sure that there’s western investment on the scale of the Marshall Plan.

And on a global scale?

You can’t stop Russia and China doing this or that down to the level of detail. You could think and talk about democracy as being a better system. It’s just better to live in Norway than it is to live in China. It’s important not to give away all of the ethical questions to people who say "nothing matters", which is the Russian position and the Chinese position. And also economically try to create a larger block of democracies. Getting democracies to disentangle themselves from Chinese or Russian economies and entangled with each other better.

We can’t say that we’ll just invent some new institution that’s going to stop China or Russia. I don’t believe in that. Don’t think that history’s on your side. Anything can happen. Democracy has more than half the world’s economy. Make that work for you.

At the same time don’t you think that everyone continuously upgrading their armies will result in an even more dangerous situation where the next conflict will be more disastrous?

No. That of course can happen, but the European Union is so far from that. The problem with the European Union is that it has no army. When they had the UK, they were the largest economy in the world. And they have no armed forces. Honestly, that’s provocative. Because the Russian army is not this big huge powerful thing. Before they started this war, the Russians had 50,000-60,000 people who could really fight. What is preventing Europe from having a European strike force of, let’s say, 60,000 people? And then, in February 2022, the European strike force goes to Zaporizhzhia or Kharkiv oblasts and says we are just having exercises with the Ukrainian army. Why not? That’s all that would have taken to stop this war. You can be so weak that it’s provocative.

But what about the nukes? Everyone’s afraid of nuclear war, not conventional war.

But they weren’t afraid of it when the conventional war started. When the conventional war started, all the Germans and all the Americans started to talk about nuclear war because that was a way to make it more about us. If you don’t want to be afraid of nuclear war, then make conventional war impossible. I take your point ‒ there’s such a thing as an arms race, there’s such a thing as too much, but the Europeans were so weak it became provocative. And it makes no sense for them to be so weak. They shouldn’t be militaristic, they shouldn’t want to go back to conquer their old colonies, but they should be able to fight a war if they really have to and not rely on the US. Because we won’t always be there or we’ll make bad decisions, there could be a wrong president or we’ll be on the wrong side. The larger questions about how to prevent the war are about deeper things. It’s about values, it’s about economics. But we can’t overlook the basic military balance.

In your article you write that defenders of the Putin regime operate as literary critics, while the Ukrainian resistance is like literature. Could you please elaborate on that?

I appreciate you asking me about that, because for me it’s a very important point. What I mean by literary criticism is Surkov. I mean the approach of applying literary criticism to life itself and to politics. And taking as your starting point that things are only as real as people believe them to be. Therefore everything is kind of permitted. There’s no such thing as a lie, there’s only perception. That is a very effective way of doing politics. The Russians invented it basically and have shown its effectiveness. If you are totally unharnessed from the world and you think everything is about criticism in the sense of taking things apart, you can create a powerful form of politics from that, because you are not afraid then to have contradictory propaganda. You can say that Ukrainians are all Jews and they are all Nazis. And it doesn’t bother you because you are living in a world which is only about taking things apart.

But then by literature I mean the act of artistic creation. I mean basically Zelenskyy. Zelenskyy is creating things with words. He’s creating a history. He’s not trying to take everything apart. The Russians were very successful as long as there was only literary criticism.

People in the West are really vulnerable to the idea that nothing is true. They feel naive when they say something is true, when they really care about something. And so Russia’s been able to work on that. But then this version of Ukraine came along and said no, some things are true, we are willing to take risks for the truth. We are willing to stay in Kyiv, we are willing to fight, there is an invasion, they really are killing our people, deporting our people, raping our people. We are creating a national story about what we are doing and we are talking about it ‒ that’s what I mean by literature. And it turns out that the best answer to literary criticism is literature.

The literary criticism is all very appealing until someone comes along and actually tells a meaningful story and then you say, oh, actually I’d rather listen to that story, I’d rather watch Zelenskyy than Surkov. Surkov is entertaining as long as there’s no Zelenskyy. It’s like the classics against the postmodern. You tell a meaningful story about democracy at war, courage ‒ it’s a very appealing classical image. The world is more interesting because there are people doing this. And then the literary criticism starts to look kind of cowardly and too easy.

Andriy Boborykin, UP