Svetlana Alexievich: Any War is Still Murder

You won’t see a Nobel Laureate in Ukraine quite often. Especially a Nobel Laureate with Ukrainian ancestry. Svetlana Alexievich was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015. Now she came to Kyiv to present the Ukrainian translations of her works. The collection is big and beautiful — four of her books were simultaneously published in Ukraine. Her ‘The Last Witnesses: the Book of Unchildlike Stories’ is due to be published in the Ukrainian language soon. Svetlana’s books are the encyclopedia of the Soviet empire, a research on the ‘red man’, who suffered himself and caused others to suffer.

Her Nobel marathon is taking a lot of effort. Svetlana is booked until the end of the year. She came to Kyiv for three days after Amsterdam. We are talking in a hotel lobby right after her arrival and before her first interview for Ukrainian television. She is tired, yet she patiently explains her books which are pierced with pain.

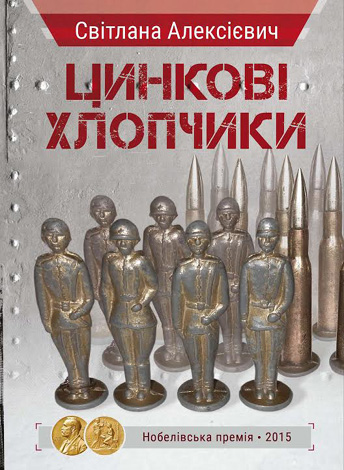

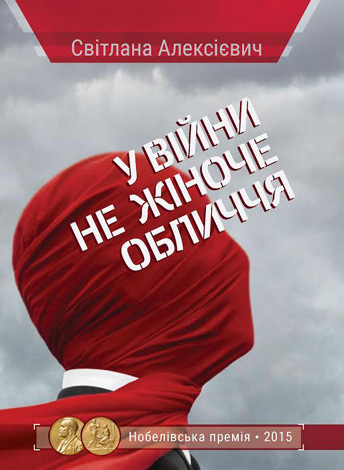

Svetlana is not a public person, she is not a sociopath either. She was chased and persecuted because of her first book ‘The Unwomanly Face of War’ about difficult destinies of Soviet women in WW2 and because of the second one — ‘Zinky Boys’ which is a painfully human account of the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. She was almost never published in her home Belarus and now she is publicly disgraced in Russia: because of Ukraine and because of the truth.

— In your Nobel speech you said you have three homelands: Belarus — the home of your father, Ukraine — the home of your mother, and the great Russian culture. Is it difficult to combine these three homes right now, when they are so mammocked?

— It is not difficult. Each human being has his own bonds and braces. Even the most politicized humans sooner or later realize that external bonds are weaker than internal ones: like life, death or love.

— Everybody claims you now. Belorussians — because you live there, Russians — because you write in Russian, Ukrainians — because you were born here. How do you manage not to offend anybody?

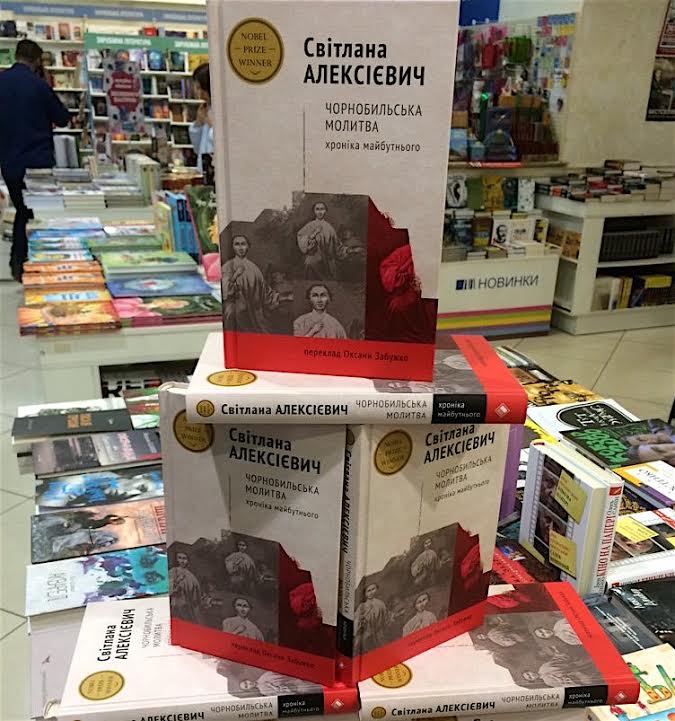

— After my book on Chernobyl [ed.: Voices from Chernobyl, published in 1997] I have no attachment to a single place. Do you know how I create my books? It is not merely collecting the material. You need philosophy, some fresh views. In Voices from Chernobyl I finally decided for myself: there is human being and there is a land on which this being lives, yet there is no attachment to a single place.

It is cute and joyful when people approach you, start telling something pleasant, hug you, take a photo. I don’t like publicity, but people have a gut feeling for some humanity, something our governments don’t have. Governments depend on artificial connections, humans on the other side do it in a natural and authentic manner.

— What ‘Ukrainian features’ have you ‘inherited’ from your mother?

— I adored my Ukrainian grandma. She was very beautiful and a perfect singer. My Ukrainian grandad died somewhere in Hungary during WW2. It was grandma who made us fall in love with Ukraine.

— You were born in Ukraine and almost died here in your infancy. I read somewhere that Ukrainian Christian nuns from Ivano-Frankivsk saved you.

— When a Japanese TV channel was making a movie about my life, we went to Ivano-Frankivsk. Next time I will be there, I have to find out who was the prioress of that monastery.

— What happened?

— It was post-war western Ukraine. My father was stationed there. Thank god he could not kill anybody as he was in an aviation unit. He always told afterwards: ‘yes, I was stationed in western Ukraine and I did not kill anybody’. Nevertheless, it was very difficult for him to part with his communist ideals.

We were robbed. I got ill and was dying. I could not eat the food from the military canteen. As a child, I needed milk. Local people hated Russian officers and did not want to sell or give them anything. So my father walked to the monastery with his colleagues.

The monastery had a huge stone wall. Somehow they managed to throw him over that wall. He walked to the cell of the prioress, followed by the nuns, who were trying to stop him. You should know my dad to understand the moment — he was quite a person, he left Minsk Communist Institute of Journalistics to fight at the frontline.

So he kneeled at the feet of prioress and said: ‘my child is ill. You are serving God’s mercy, right?’ She was quiet for some time, then she said: ‘Never come here again. Ask your wife to come.’ So for the two months after that my mother walked to the monastery, got half a liter of the goat milk from the nuns and fed me. That was how I survived.

Russian media called me ‘banverivka’ [ed.: a supporter of Stepan Bandera, Ukrainian nationalist leader in WW2] after I told this story publicly. It is such eeriness.

— As a child you spent summers in a Ukrainian village. Does it differ a lot from a Belorussian village?

— It seemed to me, that a Ukrainian village is more patriarchal than Belarusian. It gravely lacks the primitive rural life of a village. You depend on the brigade leader, he depends on the chairman of your collective farm, and the chairman is God. People had no civil rights, yet when they started speaking — I felt like I was in a Dostoevsky novel and I felt my granny was a part of that novel.

— Isn’t it the same in the Belorussian village?

— No, I felt that Belarus was different. But I should mention that I always travelled to Ukraine without my dad. In Belarus he was the protection.

— I tried reading excerpts from Zinky Boys on radio. I could not, because I started recalling my Ukrainian friends, those who are fighting right now and those who died — and I started feeling a lump in my throat. Your book is very needed in the modern day Russia as it tells the horrors of the Soviet War in Afghanistan. It helps to realize the madness of the war and aggression. People who read it might be able to stop this. On the other side: Ukrainians are defending their land, they have to go to war to stop the foreign aggression. Reading Zinky Boys might be demotivating to such people. What should they do?

— This book has several layers. There is a layer, belonging to the time when our guys were sent to Afghanistan. Yet, there is another layer as well: one man kills another man. Ultimate judgement in such cases should be left to God.

I don’t know, how it will sound to you, taking into account the current situation in Ukraine, but in XXI century you should be killing ideas, not human beings. You should talk to your counterparty, even if this person has radically different views. You cannot just kill another human because you are having a disagreement.

— When we are talking about the horrors of the war we are speaking about the two different situations: a perpetrator and a person under attack, who has to fight back not to become a victim.

— I think it is an honor to be protecting your Motherland. Yet I cannot imagine I could fire at somebody because I am pacifist. But if somebody killed a child, I don’t know what might have happened to me. WW2 was totally justified. At least until Soviet troops crossed the state border of the USSR in the opposite direction. When heroines of my book ‘The Unwomanly Face of War’ were at their deathbed, they started sending me their notes — something they were afraid to tell earlier, something they could not understand. When the book was published, Perestroika started, society was stirred and the strict societal order was abolished. My heroines started recalling their past and the permanent theme line of their reflections was ‘any war is still murder’.

It is one the major insights of that book: ‘war is still murder’. It might not be a timely insight for modern day Ukraine, but an artist cannot be one way in the 20-ies and another in the 90-ies...

— Are you primarily published in Russia?

— Unfortunately, no. My main market is Europe. It was this way even before the Nobel Prize. For example, in France my ‘Voices from Chernobyl’ were published in more than 300 thousand copies.

— Still, the Russian market matters to you. As a writer interested in being published there, you might have played along with Russia after getting the Nobel Prize and stay quiet on some issues, not to irritate the Russian government and your Russian readers.

— To get a congratulatory telegram from Putin you mean?

— Yes, to get a telegram from Putin or Medvedev. Why haven’t you done this?

— How could I respect myself after that, should I have done it? I think this is a quality of any professional: not to deceive oneself and one’s understanding of the truth. This question never existed to me. On my first press conference after the Nobel Prize I said that taking of Crimea is occupation, war in Donbass — is occupation. Mr. Peskov, press secretary for the Russian President told journalists that ‘Ms. Alexievich does not know all the details’. But I said the same things before the Nobel, it was never a question to me.

— After the Nobel, after all the interviews and morbid reaction of your Russian colleagues, have you lost many friends in Russia?

— Quite a lot. Quite a lot of good people.

— Why?

— I would like to understand why, yet I cannot find an answer to this question. What happened to Russia and the Russian elite? You know that during the recent elections many good Russian writers and artists were official representatives of Putin. Who stood out publicly? Very few: Ulitskaya, Akunin, Makarevich — you could count them with one hand.

This is an open question to me. Somebody has a son who owns a restaurant, another owns a theater — they have something to lose. In the very end: the Gulag test appeared to be easier than the dollar test. Material things are more connected to human nature. People were poor and owned nothing, then all of a sudden they became rich.

There is a good quote from Ilya Kabakov. He says that in Soviet times we were fighting an idea, a dragon. We were great, beautiful and good. We won that dragon over. Then all of sudden we had to learn living with rats. These monsters, small and big, appeared from everywhere. And we have no experience with it: neither in literature, nor in our private life. We have no experience in fighting the distributed ‘small’ evils, which are so numerous and thus powerful.

It might sound strange, but there were many idealists in the communist era. The reasons behind this were asketism, utopia and ideals broadcasted to every individual on a daily basis. I remember my youth: we believed, we sang communist songs. Nowadays our idealism is disarmed.

— Are you trying to start a conversation with your Russian colleagues?

— It is totally useless. I came to realize that it makes no sense to try convincing a person that got ‘infected’ with an idea. Only time can provide good arguments, there is no other way.

— ‘Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets’ has multiple layers and a reader can give a pull on any string. A particular quote from this work of yours came to my eye. A real estate agent wanted to become a violinist, but ended up working for old komsomol apparatchiks that quickly adjusted to the new realities of life.

He reiterates that ‘we were too fast to call it a night, so spivs and shroffs quickly took over’. I think that in nowadays Ukraine, people from Maidan were too fast to call it a night...

— Yes, marauders always come after the battle.

— How important it is to drive the Ukrainian revolution towards its completion and what should be considered completion?

— Nobody has such an experience. All revolutions are bloody, there are always grounds to say, as the time passes, that there was too much blood and savagery.

I watched the TV and I was sympathizing with Ukraine. Yet the blood was scaring me and I reflected on how hard it is to be a leader nowadays, to urge somebody’s kids to go to the square and fight for you. Remember what we did in the 90-ies, when we came to the squares? We were yelling ‘Freedom! Freedom!’ the same thing we did in our kitchens. We did it hoping this yelling and dreaming could bring about some real freedom. Now is the time of pragmatism and so revolutions became pragmatic as well. Another strange peculiarity of the modern day revolutions is that they are led by people with money.

In ‘Secondhand Time’ one of my heroines is walking in Moscow in 1993 at the time of the shootings [ed: Russian constitutional crisis]. The people who were killed are simply lying on the ground. She is walking nearby and she notices that they all have shoes with worn out heels. These plain people wearing worn out shoes came for the revolution and died there, while at the same time others nearby were agreeing on how to own Russia.

— The Ukrainian revolution, the Maidan, does it scare or attract you? How did Ukraine manage to have two revolutions already, while Belarus got just the concrete wall and Russia got its democracy degraded into counterrevolution?

— I was proud of Ukrainians when the tires started burning. I was proud that I am Ukrainian, that I have Ukrainian roots, that Ukrainians did what we failed to do in Belarus and Russia.

Yet, the inadequacy of it all is that after we all go home, the inertia of life grips us again in its deadly embrace and it becomes impossible to break through this sludge. A person now has to face it alone and this person is helpless. Under any government, especially totalitarian, like the one we are having in Belarus now, a person is totally helpless. Any scum can find a justification.

There is a story in one of my books. A young student adored his auntie Olya. She was beautiful and she sang nice songs. When Perestroika came his mother told that auntie Olya reported her own brother to NKVD and he died in prison.

It is a symbol to me. Of how people delegate all the evil to Beria and Stalin. "I was good and honest, they forced me, I had to feed my children, graduate from the institute" — thousands of pretexts.

And the evil… It turns out we are helpless against it. It is predatory, distributed and complex. Evil is more experienced than goodness.

— You actively supported Nadiya Savchenko and send her books via the Ukrainian embassy in Minsk. Did she remind you one of the heroines of ‘The Unwomanly Face of War’?

— Yes, I liked her very much. I thought such people don’t exist anymore. When I finished ‘The Unwomanly Face of War’, I realized that you could accept or reject that generation, their attitude towards Stalin — it is their youth, it all got fused together. They were wonderful people, I was admiring them. It seemed that we are different.

— Their stories looked scary. Like the one of a woman sniper...

— Or of a woman partisan who liked watching interrogations of the Nazi soldiers captured by the partisans. She wanted to see their eyeballs explode from pain. Partians did not kill the Nazis, they slaughtered them with knives. I tried telling her something about human values and she asked: "was your mother killed and your sister raped?" So I understood it is not for me to judge her.

My heroes are yelling their own truth and it is not for me to judge them. I am their storywriter and I provide a vision of the epoch, so it appears in all its horror and sometimes even beauty.

Beauty is a strange occurrence indeed. Life is artistic per se, but suffering is the most artistic. When I was writing this, I discovered how man had risen, his beauty and ugliness. Yet there is a final question: why it all does not convert into freedom? Why? In the name of what? I don’t have an answer.

— You compared Savchenko to Joan of Arc…

— Yes, she is a stunningly strong woman. She will become a symbol of an epoch. She is already a symbol. I think the Ukrainian government should be more persistent. Yet I doubt Russia can be influenced in this matter [ed: Nadiya Savchenko was captured and illegally imprisoned for 20 months by the Russian government at the time of this interview. She was released on May 25, 2016 after international campaign to release her and pleas to Putin by major world leaders].

— Probably she should not have been sacrificing her fragile life in order to become a symbol?

— These 16-year-old girls, which I describe in my book, volunteered for the frontline of WW2. 16-years-old girls shouldn’t be fighting the war, there were still some men… But it might have been their life priority. There are some things a human being should do in order to stay the way it is.

Nadiya is a composite of beliefs, creeds, hopes of human nature. It might be related to her upbringing, to her mother, I like her face. Why she should be on this hunger strike? I would like her to stay alive. This is what matters much more than other things, yet Nadiya has her own understanding.

I asked Alyaksandr Kazulin, Belarusian politician and former presidential candidate — why did he go on a hunger strike in prison? He damaged his health, his wife was in permanent stress because of that, she got cancer and died. His answer was: "I could not allow myself to give up".

|

|

|

— You were writing about an utopia, ‘the communist heaven on Earth’. In ‘Second-hand Time’ one of the heroines, Elena Yurievna, says that she is proud of the ‘Great Homo Sovieticus’ and that now she feels she is living in a country that is foreign to her. What should we do with such people, ‘the foreigners’ feeling ‘their’ country is somewhere in history, between time and space. How could they be cured?

— Such people are quite numerous. My dad died feeling that Socialism, a great idea, was betrayed. He was supporting ‘Socialism with a human face’. In truth it was he, not Socialism, who was betrayed.

Other people continue living feeling defeated. My generation thinks we were defeated. And we are the ones to blame. Freedom needs time and resources — mental, cultural, any other. Kitchen talks don’t bring about the good life. Our generation is also living in a ‘foreign country’. We cannot accept the capitalism in its harsh version that we are experiencing right now.

— Does this ‘Soviet melancholy’ differ between Russians, Ukrainians and Belorussians?

— I saw melancholy in Dushanbe as well. I felt it in Tajiks of Moscow, who are cleaning the toilets there. They say: "I graduated from university, yet I am cleaning toilets and I am treated like a dog, not a human". That communist idea had a lot of idealism, lots of good human dreams.

— I am surprised to see youngsters who miss the Soviet Union. Did their parents broadcast some myths to them?

— Why do you call them ‘myths’? Their parents told them: "I had no money, yet I could get education, free medicine, an apartment. Nowadays you are nobody, if you’ve got no money". They are right in their own way.

— People like you and me, we would have been thrown out of our jobs without the perspective of finding a new ones. Do you recall being persecuted after your first book and how they almost succeeded with destroying you after the second one?

— Yes, but ordinary people continue having an impression that it was their government, which protected them and booked their holidays at the factory resorts. This is not my thinking, I am just transmitting experiences of other people. It is all grounded on human nature: I am poor, you are poor, we all are poor. As soon as I am still poor and you are not — a conflict appears.

— It looks like auntie Olya, who considered 1937 to be the happiest year of her life, because she fell in love that year. She sold her relative out to the NKVD, he was executed, but she was happy.

— Yes, she was in Komsomol and she was happy.

— Or Germans at the times of Hitler. They were happy while 6 million Jews were burned alive.

— And only after 40 years could they start a conversation about it, despite the American presence and the Nurnberg trial...

— Could it be that the tragedy of Russia, which it imposes on its neighbors, including Ukraine, is caused by a lack of penitence or reframing of those scary Soviet times?

— I think our society is not ready for this. I imagine a village where I lived or a town of my relatives. When I started a conversation about penitence, they were indignant: "My life was so hard, why should I take penitence? Germans attacked us." Society is not ready. Many issues we are facing now are rooted in the culture and the concept of dignity.

— Decommunization is now progressing in Ukraine. The old communist toponyms are being renamed and communist monuments are being removed. Some people say it should not be done, others say that a thousand monuments to Lenin is a cult, not an art, and that a new generation won’t remember Lenin and his monuments if we simply remove them. What do you think of decommunization?

— Our failure in Russia and Belarus suggests that any actions should be fast and harsh to make any relapse impossible. And you should always bear in mind that it is possible, even in the modern Ukraine. Communist ideas are rooted deep within the people.

I read about the monument to some communist politician that was removed here in Kyiv. We discussed it with my friends in Minsk. Yes, there was some injustice: this leader did something, created something new. On the other hand: when people get rid of the old idols, they become free and can start a new life.

Imagine you are walking in Minsk. There is Uritsky Street, Zemlyachka Street, Dzerzhinsky Street. You realize all these people were monsters. Letters of the young Dzerzhinsky are outstanding. People blame me for writing about him. These are letters of a young romantic person. Yet, a power struggle starts a bloodshed.

— Are you frequently criticized for your ‘Soviet’ period?

— Sure.

— What do you respond to such criticisms?

— I love my parents, but my understanding of life is different. We had several conversations with my father. I remember coming back from Afghanistan and saying: "you are bloody murderers". He cried. I decided to leave him alone.

— The splitting of the common cultural space between Belarus, Ukraine and Russia — was it painful to you? Are you a cosmopolitan?

— I am in some sense. It happened after Chernobyl. I started seeing things differently after that life changing experience. Chernobyl threw our minds far away from our superstitions. Yet, the current situation between our countries hurts a lot.

I remember watching a movie in which fallen soldiers are being transported by cars throughout Ukraine. Women, children, everybody was standing along the roads on the path of this convoy. It was unbearable to see these boys dying. Most telling was that all of a sudden Ukraine appeared without an army and young children had to die like partridges because of that. It was hard to bear.

— Is it easier for you to talk, discuss your books with the Dutch, Germans, French people or rather with your compatriots?

— Before the Nobel 50 — 100 readers attended my meetings. Now it is 500 — 600. It is becoming increasingly difficult to deal with the powerful energy or the meeting hall. Yet it is an intellectual talk and it is politicized like any of my meetings in Europe. In our countries it is all live and painful. Even if a person is yelling at you in a disagreement, you still sympathize. Such a person is a butcher and a victim simultaneously.

— Ukrainians think that Europe is their remedy and that it will change their lives. You lived in Europe for 12 years. Do you think our people are getting the concept of ‘Europe’ right? Will it help us?

— ‘Going to Europe’ is a long path, like going to freedom. Europe cannot accept this huge burden, it already got enough of its own problems. Belorussians and Ukrainians have to create their own country and then go to Europe with that country. Otherwise it all becomes just another starry-eyed idealism.

— Empire’s final spurt — might it be the end?

— This is journalism. Empire’s final spurt is Chernobyl. It is the ground zero. When a human being reached the ultimate destruction. In our time everyman is a new hero. Listen to Lukashenka and Putin — they are speaking everyman’s language.

— We got used to Chernobyl. Belarus is building its second plant.

— We haven’t apprehended the scale of the tragedy. It wasn’t accepted into the cultural context and philosophy. We haven’t realized what has happened to us. Fukushima has a similar effect.

Some time ago I was presenting Voices from Chernobyl in Hokkaido. One of the Japanese hosts told me: "only you, crazy ignorant Russians, could have had such a tragedy. It is impossible in Japan. Everything is calculated". And what happened five years after that? All of Asia was covered with radiation. The arrogance of the technology passes away. We come to understand that we are powerless against nature.

— And Lukashenka is building another nuclear power plant...

— He does not understand the consequences. What is dictatorship? It is lack of culture.

— You were severely persecuted back home. Did your life improve after the Nobel Prize?

— People changed their attitude. More people started reading my books. I cannot say the same about my government, but it is complicated. Western politicians tell me that when Belarusian government officials go abroad, they boast of Ms. Alexievich. However, when they return home — not a single word comes from them.

— President Lukashenka and Belarusian diplomats are giving your books out as a gift.

— It is kind of a game. But speaking in a broader sense, I am interested in exploring everything, even something evil. It is an intellectual puzzle: a game of how and why? I don’t hate anybody.

— So you don’t have malevolence?

— No, I am not interested in this.

— And all those criticisms, stating that your books are not literature but journalism, do they offend you?

— They all are personal opinions. That is why I am upset to hear this from writers who matter. I think they simply might have not read my books before criticizing. A professional writer should see the work behind my stories. I am writing my new book for almost eight years now. It will be about love. Despite the massive amount of research, it is still a mess. My material in its current state lacks philosophy. In order to understand it, you should look at it with a fresh eye, perceive a lot of stories about love.

— Is it so difficult to make a puzzle out of all those conversations while preserving the main storyline?

— Is is a kind of voices novel. Everything is changing and you don’t have 50 years like Leo Tolstoy when he was writing War and Peace. You don’t have this time. It is a time of witnesses, everybody comes with his own mystery.

— It is interesting. All your previous works are about utopia and tragedies, yet now you ended up writing a book about the love and death.

— Love and death are irrelevant to my new stories. After finishing my previous works I realised that I told everything I could about the ‘red utopia’. And started thinking where else this genre might be relevant. It needs a mixture of epic space, a lot of heroes, a broad major theme that encompasses social aspects and metaphysics. This is very complicated and it does not always work, turning an author’s work into mere journalism. And what is life’s leitmotif? It is love and death.

— Isn’t it the wrong time to discard your theme of the ‘communist utopia’? Many are afraid of a global catastrophe, a new Word War.

— It looks like some kind of hysteria. It is useless to try forecasting the future right now. As you see, futurologists and, undoubtedly, politicians fail in their analysis quite often.

It might take different turns. Who thought of ISIS and radical Islamists? The future is unpredictable. But we might need to face fascism.

— Where we might face it from?

— It is quite possible in Russia. You should drive out of Moscow or St. Petersberg and it is all virgin wildlands there. Everything is possible and there is enough ground for that. Especially when you listen to the sermons of the Russian Orthodox Christian preachers and realize what they are preaching for.

— How did your life change after the Nobel?

— I do not belong to myself. I am waiting for next November, when a new hero will arrive.

— So the public is stealing you for quotes?

— I can’t call this ‘quotes’. Sometimes you talk to someone on a plane and the next day you read your words in a newspaper. It makes me feel uncomfortable.

— Why uncomfortable? Your are writer, you should be open to the world.

— I think you should come out to the world with your ideas well prepared and structured. Not just by sitting and talking to someone on a plane. This is not a deep and lasting approach. Professionals should be professional.

— It is a stupid question and I realize that if might be difficult for you to answer, but you have a number of books and it is evident that it might take people too long to read all five of your books because we are always in a hurry nowadays. Which book would you recommend them to start with?

— Actually, you are the first person to ask me such a question and it is really difficult. I love each of my books in a different manner. ‘The Unwomanly Face of War’ is about women and nature against the violence and the running roller of the time. ‘Voices from Chernobyl’ is intellectual. There was nothing to base my reasoning on, as such disasters never happened before. War books are about the culture of war and there were enough references and benchmarks for that. The Chernobyl theme was completely new and difficult. It took me 11 years to write that book.

‘Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets’ was also difficult. Everything got shattered to atoms and it was very difficult to make this puzzle work. It was full of thoughts that I cherish.

Pavel Sheremet, Ukrayinska Pravda. Translated by Gennadiy Kornev.

Nota Bene! Publications of the English version of Ukrayinska Pravda are not verbatim translations of the source publications in the Ukrainian or Russian language versions of our website. For the sake of clarity and editorial effectiveness our translators might take the liberty of shortening and retelling parts of the source publications. Please consult the text of original publication or the English editorial staff of Ukrainska Pravda prior to quoting our English translations.